Under the banner of “Silk Road Treasures”, TCA’s people – journalists, editors, authors – share their personal experiences of Central Asia and her people, and by listing their favorite places, literature, films, art, architecture and archaeological sites, alongside encounters with customs and traditions, provide pointers for readers wishing to visit the region.

Stephen M. Bland – Senior Editor and Head of Investigations

Architecture: Bukhara – The Kalon Trinity

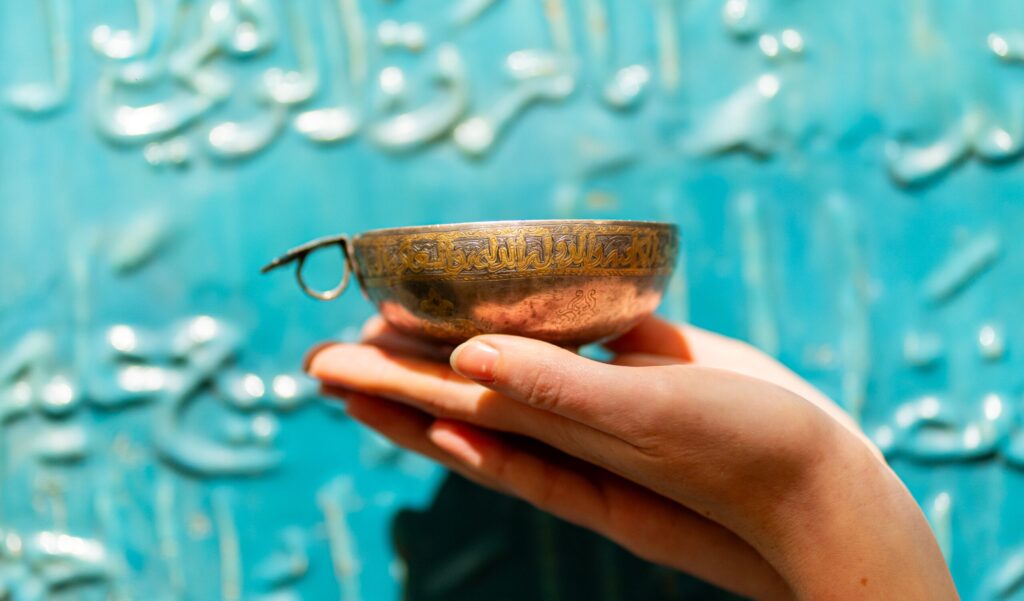

The Kalon Mosque, Bukhara; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

From the ninth century Pit of the Herbalists to the Ismail Samani Mausoleum and the bird market, the old town in Bukhara isn’t really about its separate sights, it’s the sum of its parts, the timeless city permeated by an air of antiquity like a window into the past. That having been said, however, the jewel in the crown of Bukhara is the trinity of the Kalon Mosque, Minaret, and the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah.

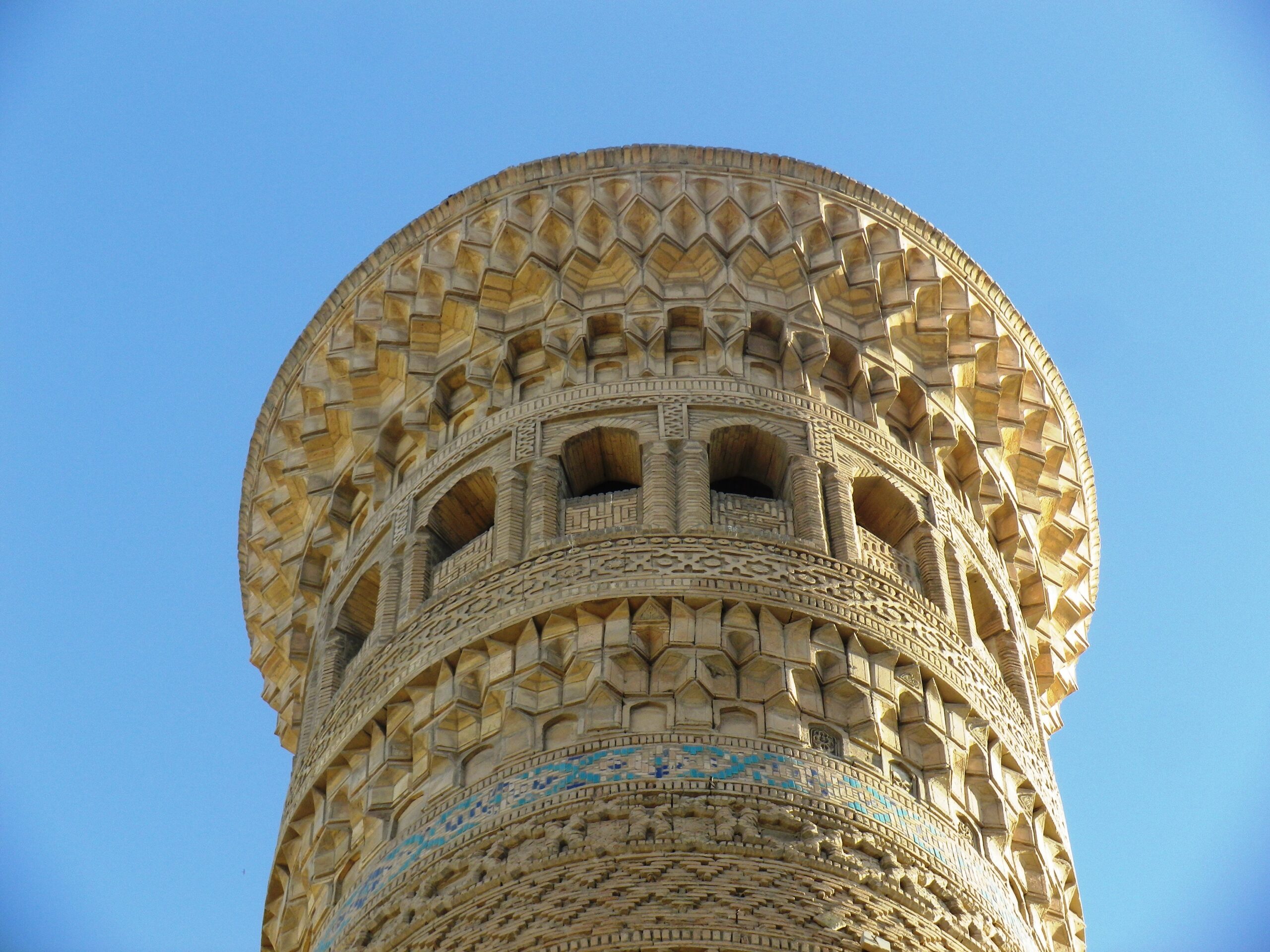

Built as an inland lighthouse for desert caravans, the Kalon Minaret – “great” in Tajik – was probably the tallest building in Central Asia upon its completion in 1127. The third minaret to have been built on this site, previous incarnations had caught fire and collapsed onto the mosque below, officially because of the “evil eye.” Also known as the “Tower of Death,” over the centuries the minaret has seen countless bodies sewn into entrail catching sacks and tossed from its 47-meter-tall lantern. Particularly popular during Manjit times, this practice survived until the 1920s.

The lantern of the Kalon Minaret, Bukhara; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Home of the first recorded use of the now ubiquitous blue tile in Central Asia, the 14 distinct bands of the minaret are majestic in the pink evening light, its scale and intricacy remarkable. While the sense of history lingers, everyday life continues unabated at its stout base, and when the heat of the day abates, head-scarfed babushkas sat chit-chatting on the cool stone steps of the Madrassa, while kids kick soccer balls against the ancient stones.

Art: The State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, Nukus

Lev Galperin – “On his Knees”

Once a thriving agricultural center, Karakalpakstan is now one of the sickest places on Earth. Respiratory illness, typhoid, tuberculosis and cancers are rife, birth defects and infant mortality rates amongst the highest in the world. The deliberate destruction of the Aral Sea for irrigation purposes has caused toxic dust storms so vast they are visible from space, ravaging a 1.5-million-kilometre square area. Spreading nitrates and carcinogens, these storms used to hit once every five years, but now come ten times a year.

Yet it is in the capital of Karakalpakstan, Nukus, that a remarkable collection of art has survived in part because of its inhospitable location. Risking denouncement as an “enemy of the people,” obsessive Ukrainian-born painter, archaeologist and art collector, Igor Savitsky spirited away thousands of avant-garde pieces banned in the Soviet Union. In this farthest-flung corner of the former empire, the State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan houses works by a forgotten generation. A mishmash of styles and influences far removed from the purportedly uplifting romanticism which Socialist realism had permitted, many of the artists displayed here met with an unsavory end.

Featuring dazzling, geometric scenes of everyday Central Asian life, the oil paintings of Aleksandr Volkov are awash with color. When the campaign against free-thinking artists began in the USSR following an edict from Stalin, his Cubo-Futurist vision saw Volkov labelled a bourgeois reactionary. Fired from his posts, he lost everything. Over the course of the next three years, all of Volkov’s works were removed from the leading Russian galleries. Up until his death in 1957, upon orders from Moscow, he was isolated from any contact with artists, critics, or art lovers. To anyone who wanted to meet Volkov, they declared that the painter was too ill to see them. Still, in many ways Volkov was one of the lucky ones, for at least he avoided the gulags.

A fusion of Dada and Cubism, a piece entitled On His Knees is most likely the sole surviving work by Lev Galperin, a well-travelled painter and sculptor from Odessa. No longer permitted to leave the Motherland after returning in 1921, he eked out a meagre existence working to order on bas-reliefs. With his paintings adjudged to be counter-revolutionary, he was arrested on Christmas Day of 1934 and sentenced to five years hard labor. During his trial, Galperin dared to voice his skepticism regarding the Soviet system and the state of art in the union. His death certificate simply reads, “Cause of death: execution by shooting.”

Sketch of a gulag by Nadezhda Borovaya

A series of sketches by Nadezhda Borovaya show what conditions in the gulags were like. When her husband was executed in 1938, Borovaya was sent to the Temnikov Camp, where she spent the next seven years secretly recording and smuggling out scenes of everyday life. With dazzling bravado, Savitsky procured government funding to purchase these drawings by persuading party officials they were depictions of Nazi concentration camps.

Film: The Killer by Darezhan Omirbaev

Poster for The Killer by Darezhan Omirbaev

The Killer is a crime drama from 1998 directed by minimalist Kazakh filmmaker and screenwriter, Darezhan Omirbaev, which won the Un Certain Regard Award at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival and the Don Quijote Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. A sparse, tensely-drawn, but simple tale, the film tells the story of the seemingly inevitable demise of chauffeur in Almaty, who, following a string of unfortunate events, accepts a loan from a mafia boss. Whilst unremittingly bleak, it is perfectly paced, shot, and acted, and, as noted by Variety, has “its own type of beauty”.