Against the backdrop of the silence of Central Asian countries, as well as their lack of a coordinated position on the construction of the Qosh Tepa Canal in northern Afghanistan, the Taliban are moving forward with the project with growing confidence and without regard to their neighbors.

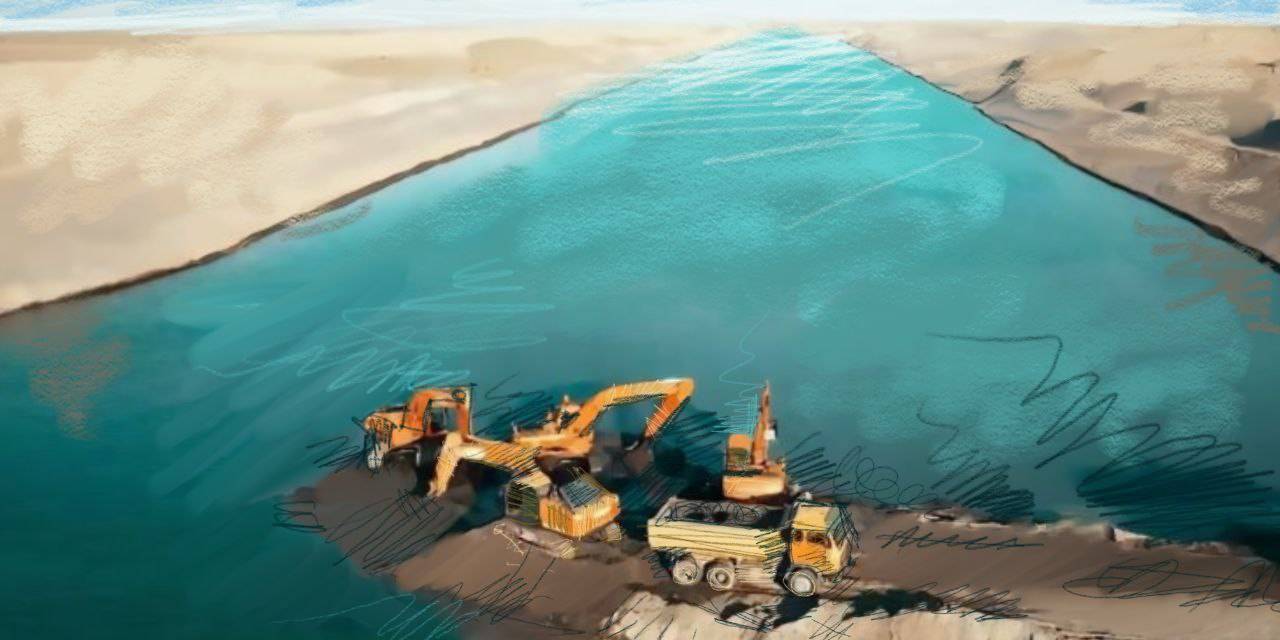

Last October, at the ceremony to mark the launch of the second phase of the canal’s construction, Afghan Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Salam Hanafi called Qosh Tepa, “one of the most significant development projects in Afghanistan,” while its realization should remove all doubts about the capabilities of the new Afghan authorities, he added.

There is no point in discussing the economic rationale for the canal; like other practical measures taken by the Taliban in the water and energy sphere, for Afghanistan, where 90% of the population is employed in agriculture, the provision of irrigation water is undoubtedly an important task. According to the UN, over the past four decades, desertification has affected more than 75% of the total land area in the northern, western, and southern regions of the country, reducing the vegetation of pasture land, accelerating land degradation, and impacting crop production.

However, this socio-environmental problem affects the interests of all the peoples of Central Asia, which geographically includes the entire north of Afghanistan. It arose as an objective need for development, and solving it requires the combined efforts of all countries in the region, which is already on the verge of a serious water crisis that threatens not only economic development, but also the lives of millions of people.

In general, the Taliban have emphasized their openness in matters of trans-boundary water management, but, so far, these are only statements. They are more motivated by political issues around their international recognition. That is why it is important for them to participate in global events, such as UN climate change conferences, but they have yet to take part in any climate talks. Hopefully, Afghan representatives will be invited to the COP29 Global Impact Conference in Baku this November, especially since one of the key topics of this forum will be a “just energy transition.” It would be interesting to hear what the Taliban have to offer.

Though the authorities in Kabul have had some success in water regulation with Iran, the same cannot be said about Central Asia. This clearly owes to the fact that the five Central Asian republics have not taken a unified position on trans-boundary waters with Afghanistan. And their southern neighbor has taken advantage of this – to date, Kabul has not held any full-fledged official consultations with any Central Asian country on the Qosh Tepa Canal.

However, just as bilateral formats will not yield results (unlike in Iran’s case), the Taliban leadership will not be able to resolve water issues easily with the Central Asian countries.

Afghanistan is not a party to the Central Asian Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Joint Management on the Utilization and Protection of Water Resources from Interstate Sources. It was signed in Almaty back in 1992, at the dawn of the independence of the five republics, while a civil war was raging in Afghanistan.

Back then, the Central Asian states relied on the regulatory base between the USSR and Afghanistan, which in one way or another regulated the use of trans-boundary waters, including the Treaty Concerning the Regime of the Soviet-Afghan State Frontier (1958), Protocol between the USSR and Afghanistan on the Joint Execution of Works for the Integrated Utilization of the Water Resources in the Frontier Section of the Amu Darya River (1958) and the Agreement on Joint Study of the Possibilities of Integrated Use of Water and Energy Resources of the Pyanj and Amu Darya Rivers (1964), among others. In addition, the Agreement on Cooperation in the Development and Management of Water Resources of the Pyanj and Amu Darya Rivers was signed by Tajikistan and Afghanistan in 2010.

Qosh Tepa, referred to as a “national pride project” in Afghanistan, is of strategic importance for the country. However, it is sure to have a negative impact on the countries located in the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. You do not need to be an expert to understand this. In the absence of dialogue and transparent actions, this rhetorical threat may turn into a very serious, real challenge for the countries of Central Asia in the near term.

In the spirit of geopolitical rivalry, all sorts of political theories and opinions have sprung up around the Qosh Tepa project.

For example, opponents of the Taliban have declared their intention to populate the future fertile areas along the canal with Pashtuns from the east of the country, including repatriates from Pakistan and families of members of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, which would be a blow to natives of the north (Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmen, and Hazaras).

Another version is that the region along the Qosh Tepa will be a magnet for the terrorist organization Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), which, it is argued, will create sleeper cells here with an eye to Central Asia. Moreover, according to this version, ISKP will use the Qosh Tepa Canal to intensify the fight against the Taliban and turn “national pride” against the Taliban, at whose hands all the peoples of Central Asia would suffer.

Anti-Western versions point to plans for the U.S., claimed to be financing the project, to play the “water card” in Central Asia through Qosh Tepa and thereby have greater influence in the region. It would also oppose Chinese interests, such as the development of oil fields in northern Afghanistan and the Belt and Road Initiative.

All these versions have one thing in common – direct threats to the countries of Central Asia, which, of course, cannot but alarm them. However, currently, the Central Asian countries are taking a wait-and-see approach, preferring to work with Afghanistan bilaterally, even though, it must be noted, there are no results to be seen.

It is important for the Taliban to understand that water cannot be a subject of bargaining and should not be considered a lever of political and economic pressure on Afghanistan’s northern neighbors. The Central Asian countries have acquired existential experience in dealing with issues of joint water use and can act as a united front to protect their interests.

The Central Asian countries proceed from an understanding that one way or another, the Qosh Tepa Canal will be operational, and in the future new precedents for water use will arise on the long border with Afghanistan (the total length is over 2,292 km of which more than 1,298 km is a river). It is important how this and other projects in this sphere will turn out. It remains unclear whether the canal bed will be lined – which would prevent significant loss of water – whether technical standards will be followed, and what the regime for servicing the complex hydraulic structure will be, among many other questions to be answered.

Water is a sphere for joint, responsible decisions. The Qosh Tepa Canal may, in fact, be the starting point for, as the Taliban themselves claim, the development of good neighborly relations based on mutual respect. This is especially true given the growing regional paradigm around Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, the Central Asian countries do not need to come up with a new institution for dialogue with Kabul – the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) has been around since 1993, described by Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev at the IFAS summit in Dushanbe in September 2023 as “one of the few successful mechanisms of regional cooperation, demonstrating the agency of Central Asia in the international arena.”

Nothing prevents Afghanistan from joining this Central Asian club on water issues. For a start, Afghanistan could be granted observer status in the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC), which is the only body in Central Asia authorized to make binding decisions on current and future issues of interstate water allocation and use.

There is no other way for the Taliban, since on the issue of joint water use Central Asia has agency and is expanding it.

Aidar Borangaziev is a Kazakhstani diplomat with experience in diplomatic service in Iran and Afghanistan. He is the founder of the Open World Center for Analysis and Forecasting Foundation (Astana) and an expert in regional security research.