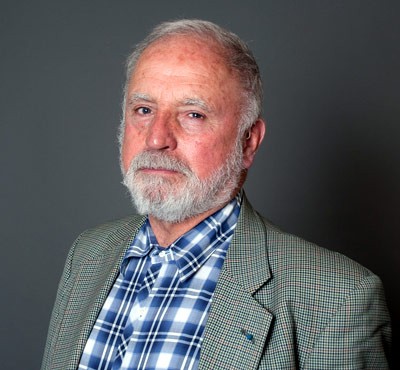

BISHKEK (TCA) — The death of President Karimov is watched by International media and all Central Asia republics, as well as such powers as Russia, China and the United States, due to the fact that what will happen next in Uzbekistan may outline a future scenario and alliance of the entire Central Asia. The following article is an excerpt from what has been written by Rene Cagnat, an expert in Central Asia, who for many years served as the military attache at the French Embassy in Tashkent. Now Mr. Cagnat is living between Paris and Bishkek, and the following excerpt was translated from French into English by The Times of Central Asia. The full article in French can be read here

Uzbek President Islam Karimov is dead. The official announcement was given with some delay although rumors were circulating since August 31, 2016. At that time the Uzbek and Russian TV kept silent, probably waiting to see some sign of internal negotiations to organize a difficult succession in a region marked by a mafia Islamism that could become a rear base for Daesh fighters now seriously troubled in the Middle East.

It is crucial to realize the importance of Karimov’s death, the man who for 26 years led Uzbekistan with unparalleled strength. In the complicated organization of Central Asia left in 1991 by the Soviet regime, we can say that this great country, in contrast with the other four Central Asian nations, is a kind of key to the whole of Central Asia. Now, after the death of the “boss”, this situation may change with a risk to enter into a civil war that may divide the country and the whole mosaic of Turkestan, and even redesign the borders with its surroundings: a task almost impossible to achieve.

As did Stalin in 1953, the Uzbek dictator seemed to have planned his replacement in power: the Karimov system, built over the years under the surveillance of the State Security Service (SNB), is of such strength that the dictator had no need to appoint his successor by name. In his mind, it was enough to rule out his daughter Gulnara, and make room for the hierarchs used to working together for years. Karimov also underestimated the rivalries and intrigues “a la Uzbek” that had developed among his entourage toward problems, mainly economic, that were always present but never resolved, and that would rebound sharply. Isolation and an iron fist are what is needed to ensure the continuity of the regime in the case of Uzbekistan, but continued isolation and absolutism seems hardly possible in the twenty-first century in a world which, in its globalization, is losing part of its national characteristics.

The disappearance of the “Boss”, who used to be everything and is suddenly nothing now, is going to result in many questions and may lead to a new equilibrium. For Uzbekistan and Central Asia, the present situation may have the same destabilizing effect as had the death of the Father of the Peoples in the USSR and its periphery.

It is doubtful that the new Uzbek leadership will be able to keep an iron grip while allowing the hope that things may change.

A country divided as its leadership

The 32 million of so-called Uzbek citizens, in fact multiethnic, felt unsecured on September 1, 2016 when a national holiday was not celebrated.

In the absence of an organized opposition, the Uzbeks, who mainly descend from the Sart population resulting from all invasions, and the last nomadic invaders of the sixteenth century — called Uzbeks, generally demonstrate their status of dehkans, the farmers of oases of great docility that may once again kowtow.

But Uzbekistan is far from being monolithic and libertarian spurt could find energy in various provinces traditionally opposed to Tashkent, often along ethnic lines, where there is permanent division since the eighteenth century between the Emirate of Bukhara, the sultanate of Khiva and the Kokand khanate, whose eternal rivalry was at the origin of their collapse to the Russians.

Potential successors

The Tashkent clan has is main representatives in the persons of Rustam Azimov, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, and Speaker of the Senate Nigmatulla Yuldashev. After Karimov’s death, they would act against the clan of Samarkand.

Each province and every big city has its clan that favors the promotion of its man at the expense of others, which divides the Uzbek elite.

Only one person in the government in Tashkent has the same power and authority as Islam Karimov and inspires almost as much fear: it is Rustam Inoyatov, head of the omnipotent National Security Service (SNB). But Inoyatov is 72 years old and suffers from diabetes. He would rather be a “kingmaker”.

Like many others of his generation, Inoyatov is a Soviet Uzbek, meaning that he remains oriented at Moscow and the Putin-like “vertical of power” would suit him well. Under such conditions, the head of SNB would favor the possible successor that would be supported by Russia. It is the current prime minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, aged 59, in place since 2003 and member of the Samarkand-Jizzakh clan. Shavkat is a resolute person, even brutal, in the tradition of Karimov.

But there are other contenders: Rustam Azimov, deputy prime minister and minister of finance, and Elyor Ganiyev, minister of trade and external economic relations. Both of them are considered oriented at the West.

If problems emerge, as in the USSR in 1953, a troika or a provisional quartet (Inoyatov-Mirziyoyev alliance plus Minister of the Interior Adkham Akhmadbaev and Defense Minister Kabul Berdiev) may form a government of “public salvation”. This scenario seems the most plausible as the severity of the outstanding issues is considerable.

* René Cagnat, doctor of political sciences, associate researcher at IRIS, is a specialist in Central Asia. He lives in France but spends much of his time in Kyrgyzstan