Once a flourishing hub of agriculture, Karakalpakstan has been transformed into one of the most perilous environments on Earth. Rampant health crises, including respiratory diseases, typhoid, tuberculosis, and cancer, plague its population. Birth defects and infant mortality rates are alarmingly high. The root of this devastation lies in the deliberate collapse of the Aral Sea, drained for irrigation, which has triggered toxic dust storms blanketing a 1.5 million square kilometer area. Carrying carcinogens and nitrates, these storms, once rare, now strike ten times per year, spreading sickness and despair.

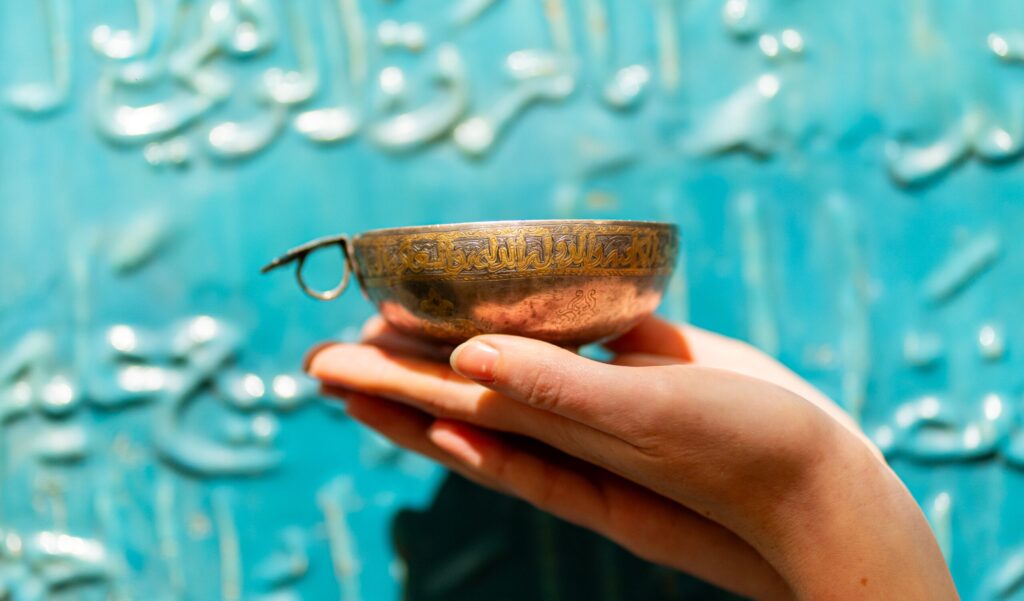

The State Museum of Karakalpakstan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Amid this harsh and desolate landscape lies a surprising beacon of cultural preservation — the State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, located in its capital, Nukus. Its existence is extraordinary, not least because of how it came to be and how it has endured. Protected by the remoteness of the region, this museum safeguards one of the most remarkable collections of banned avant-garde art, amassed through the daring vision of Igor Savitsky. The Ukrainian-born painter, archaeologist, and art collector defied the Soviet regime, risking being labeled an enemy of the state, to rescue thousands of prohibited works. These pieces, forged by a forgotten generation of artists, now provide an extraordinary glimpse into a turbulent period of history.

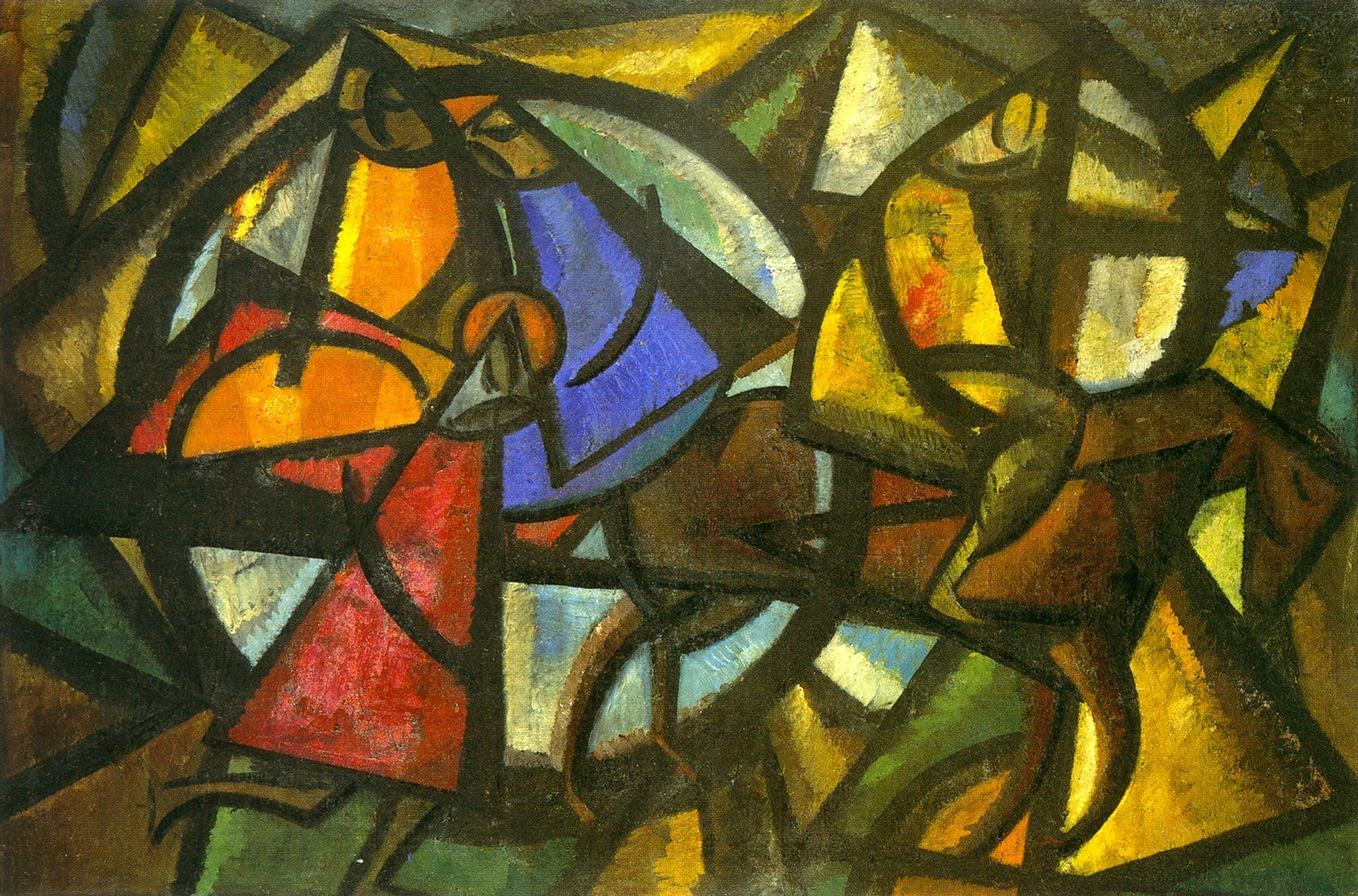

Aleksandr Volkov, Chaikhana with a Portrait of Lenin; image: TCA, Stephen M.. Bland

Among the luminaries memorialized in the museum is Aleksandr Volkov, whose vibrant oil paintings brim with the energy and colors of Central Asian life. Born in Ferghana, his Cubo-Futurist style clashed sharply with Stalin’s Soviet ideals, leading to his ostracism as a bourgeois reactionary. Dismissed from his roles and expelled from Russian galleries, Volkov lived out his final years in isolation, banned from contact with the artistic community. Though he escaped the gulags, he was silenced until his death in 1957 under orders from Moscow. Volkov’s work, a symphony of geometric brilliance, survive today as a testament to his resilience.

Lev Galperin, On His Knees; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Painted defiance is also seen in Lev Galperin’s surviving piece, On His Knees. A unique fusion of Dada and Cubism, it represents his bold challenge to Soviet authority. Galperin, a well-traveled artist from Odessa, returned to the Soviet Union in 1921 only to be ensnared. Arrested on Christmas Day in 1934 for his so-called counter-revolutionary art, his trial marked him as an outspoken critic of the regime. Sentenced to execution, his sole piece saved from oblivion speaks of his courage and the high cost of dissent.

Nadezhda Borovaya, Sawing Firewood; image: nukus.open-museum.net

The gallery also hosts haunting sketches by Nadezhda Borovaya, which vividly document life in the Soviet gulags. Borovaya’s tragedy began in 1938 when her husband was executed, after which she was exiled to the Temnikov camp. There, she clandestinely captured the harrowing realities of camp life. Savitsky acquired these pieces by obtaining funding after convincing party officials they depicted scenes from Nazi concentration camps, preserving Borovaya’s testimony.

More than a gallery, the State Art Museum in Nukus holds the stories of artists crushed yet remembered through their work. Despite being plagued by further political turbulence over the course of the last decade – purportedly for attracting attention to Karakalpakstan – against a backdrop of environmental catastrophe, it stands as a monument to the enduring spirit of art and resistance.