An Early European View of Nomadic Central Asia

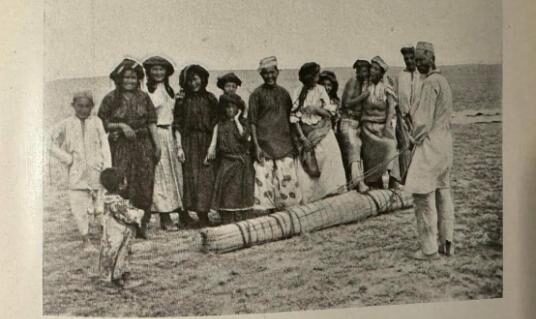

During a period when Central Asia remained largely unknown to European audiences, Among Kirghiz and Turkimans offered Western readers a rare first-hand account of the vast steppe and desert regions. The book was written in the late nineteenth century by Richard Karutz, a German traveler whose work belongs to the broader tradition of European exploratory travel literature. I first encountered this book while studying in the United States and later incorporated it into my research. A copy preserved in the library of the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., was published in Leipzig in 1911. Since then, it has been regarded as one of the more noteworthy works in early European writing on Central Asia. Who Was Richard Karutz? Richard Karutz was a late nineteenth-century German traveler and writer who journeyed through parts of the Russian Empire’s Central Asian territories. Though not widely known today compared to some British or Russian explorers, Karutz represents a generation of European intellectuals fascinated by the perceived “frontier zones” of empire, regions seen as remote, exotic, and culturally distinct. [caption id="attachment_44400" align="aligncenter" width="312"] Richard Karutz[/caption] He was neither a colonial administrator nor a military officer; rather, he traveled as an independent observer. His writings reflect the curiosity of an educated European shaped by the intellectual currents of his era, including Orientalism and the growing interest in ethnography. Like many travelers of his time, Karutz sought to document ways of life he believed were on the verge of transformation under imperial modernization. Across the Steppe and Desert In Among Kirghiz and Turkimans, Karutz traveled among communities then commonly referred to in Russian and European sources as “Kirghiz”, a historical term often applied to Kazakhs, as well as Turkmen tribes. His route took him across vast grasslands, caravan routes, and oasis settlements shaped by pastoral migration, tribal organization, and Islamic traditions. Rather than producing an official report or military survey, Karutz wrote in a personal and descriptive style typical of travel literature. His narrative often reads as impressionistic reflection rather than systematic analysis. He documents everyday life, including nomadic encampments and felt yurts, equestrian culture and elaborate codes of hospitality, tribal leadership and clan loyalty, as well as desert trade routes and caravan movement. Mangyshlak, a peninsula on the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea in present-day Kazakhstan, features prominently in his descriptions. Significant mineral deposits were later discovered there, leading to its designation as a “peninsula of treasures.” Mangyshlak is characterized by stark desert landscapes and was once described as a barren land consisting largely of sand and stone. In the Middle Ages, it served as a gateway for trade between East and West. The region also played a role in the early history of Turkmen communities. Karutz’s writing attempts to capture both the hardship and the quiet grandeur of steppe existence. Depicting Nomadic Society A central strength of the book lies in its attention to social organization. Karutz was particularly struck by the mobility of Kazakh life, seasonal migrations, a livestock-based economy, and...