The China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway (CKU railway), also known as the Kashgar–Andijan railway line, is more than an infrastructure project. It represents a geopolitical initiative that could significantly shape the future of Central Asia.

In June 2024, Beijing, Bishkek, and Tashkent signed the intergovernmental agreement to move the project forward. The project’s financing—estimated at $4.7 billion—was finalized in December 2025, sparking optimism in all three nations about regional connectivity, trade, and economic growth. Once completed, the railway is expected to become a vital strategic asset in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

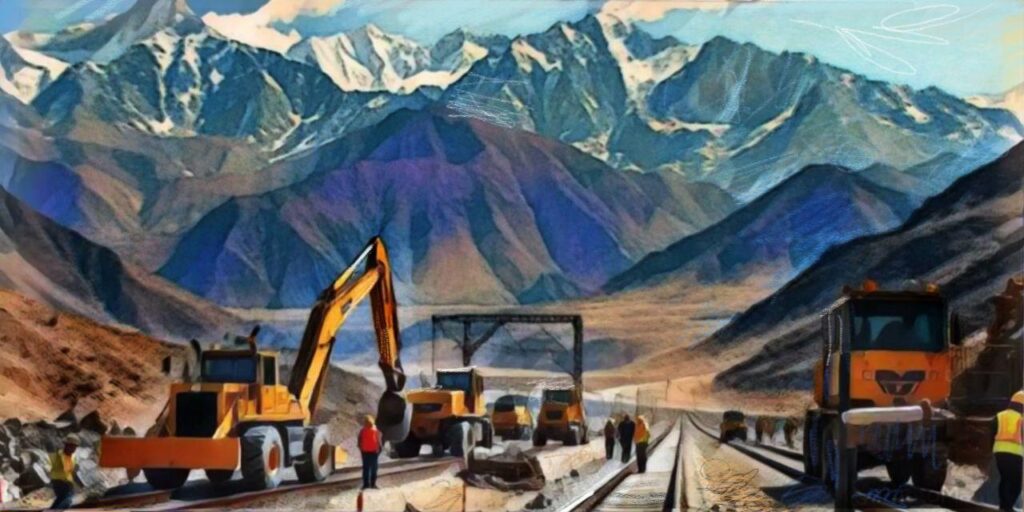

From China’s perspective, the CKU project is a strategic line that diversifies its trade channels and strengthens overland access to Central Asia and beyond. Construction was ceremonially launched on 27 December 2024 in Kyrgyzstan, with major works progressing through 2025, including key tunnel works. For Uzbekistan, the railway could serve as a key link for commerce and transit. Tashkent aims to integrate the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan line with existing international transport networks, including connections through Iran and Turkey. But how important is the project for Kyrgyzstan, through which, according to recent reporting, 304 km of the line will pass?

According to Nurbek Satarov, Presidential Envoy in the Naryn Region, the project is vital for Kyrgyzstan’s most mountainous region, as roughly 90% of the route through the country will run through Naryn. As he told The Times of Central Asia, construction is in full swing, and the railway is expected to be completed between 2028 and 2030, despite the challenging terrain and technical difficulties.

The project includes the construction of 50 bridges and 29 tunnels, underscoring the significant engineering complexities involved. But while regional and national authorities anticipate direct economic benefits from the project, critics argue that Kyrgyzstan may end up serving primarily as a transit country, with limited gains for the local economy. They also question the financial sustainability of the project, noting that it is backed by a long-term loan package of approximately $2.3 billion from Chinese banks. The financing, structured over 35 years and to be repaid by the joint venture company implementing the railway, increases Kyrgyzstan’s exposure to China-linked debt and has raised concerns about future repayment obligations.

Site visit at the road construction project in the Naryn Oblast; image: TCA, Nikola Mikovic

However, Edil Baisalov, Kyrgyzstan’s Deputy Prime Minister, claims that the CKU will have a positive impact on the country’s economic development.

“This railroad will virtually transform Kyrgyzstan – and not just Kyrgyzstan, but the whole of Central Asia,” he told The Times of Central Asia.

Baisalov believes that the CKU railway, once completed, will be part of a larger transcontinental railroad that will cut transit times by at least seven days compared to the northern routes of the Trans-Siberian Railway and maritime transport.

The CKU line could indeed bypass the usual northern rail routes through Russia and Kazakhstan, taking a significant share of freight from those countries and reducing their transit revenue. Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand, hopes to see direct gains from the project.

“Even under the most pessimistic scenarios, the cargo loads expected to transit this route could generate at least $300 million in annual revenue, benefiting the country significantly,” Baisalov emphasized, pointing out that the CKU railway will help Kyrgyzstan increase exports of its natural resources.

As he explains, the Naryn region is rich in coal, iron, aluminum, and rare earth elements, but these resources remain largely untapped because there is no railway to transport them efficiently.

“Our mineral deposits are world-class. During the Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan’s mineral base was largely ignored in favor of deposits elsewhere. The Soviets focused only on uranium here, which was used for their first nuclear bomb, but otherwise, industrial development was minimal. As a result, Kyrgyzstan remained mostly agrarian, producing meat, wool, cotton, and tobacco. Now, with this railway, the country’s mountainous wealth can finally be accessed,” Baisalov stressed, adding that the CKU project will serve not only to export raw materials but also to support the construction of metallurgical plants, steel mills, aluminum facilities, and other industrial enterprises.

He maintains that Kyrgyzstan’s ample energy capacity positions it well for industrial expansion. Despite the global transition in energy use, he believes demand for iron, aluminum, and other key industrial metals is likely to remain strong. Moreover, in his view, the railway will reshape not only Kyrgyzstan’s trade flows but also the country’s entire economic landscape.

“The railroad will also stimulate manufacturing and logistics. International investors are already building logistics centers and assembly facilities along the line, leveraging the region’s labor force. Several towns will develop along the transcontinental railway, with direct access to markets in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Southeast Asia,” Baisalov concluded.

At present, routes from China to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan rely on transit through Kazakhstan’s rail network, as there is no direct rail link from the People’s Republic to either country. Once completed, the project will, at the very least, enhance regional connectivity. However, the extent to which it delivers financial benefits to Kyrgyzstan will likely depend on transit volumes, tariff policies, and the country’s ability to develop complementary industries along the route.