On January 30, David O’Sullivan, the European Union’s Special Envoy for Sanctions, made his fourth visit to Kazakhstan. Following the visit, he gave a briefing in Astana, where he discussed the new sanctions package, which could theoretically include Kazakh companies that assist Russia in circumventing restrictions.

What O’Sullivan Said

According to O’Sullivan, only companies with indisputable evidence against them of involvement in violations will added to the sanctions list.

“We are currently working on preparing a new, 16th package of sanctions. It is possible that Kazakh companies may be added to the list, but no decision has been made yet. We conduct a detailed analysis of companies, examine their trade relations, and review the goods they have previously traded. Of course, we prefer to work with governments to find a systematic solution rather than simply adding individual companies to the list. However, when there is no other option, we do add them,” O’Sullivan explained.

The EU Sanctions Envoy reiterated that the EU remains one of Kazakhstan’s key economic partners, with mutual trade turnover reaching nearly 40 billion euros per annum. The EU accounts for 38% of Kazakhstan’s exports and 55 billion euros in direct foreign investments.

Highlighting the importance of economic ties, O’Sullivan stated that the EU fully respects Kazakhstan’s position on sanctions, but urged authorities to take strict measures against third-party entities using the country’s trade channels.

“We have concerns that unscrupulous actors may try to use Kazakhstan as a platform to circumvent our sanctions,” O’Sullivan warned, pointing to the import of high-tech goods such as microchips, sensors, and circuits, which have been found in Russian drones, missiles, and artillery shells.

O’Sullivan noted that these goods, listed in an open “common high-priority list” of 50 codes, are not produced in Kazakhstan but are allegedly being re-exported from EU and G7 countries through Kazakh intermediaries. While they make up less than 1% of Kazakhstan’s total trade volume, O’Sullivan emphasized that these are “lethal products that kill innocent Ukrainian civilians.”

The special envoy recalled that in 2024, the EU blacklisted two Kazakh companies and issued a warning that this list could be expanded. He noted that particular attention is being given to companies that emerged immediately after the invasion of Ukraine and the start of the new sanctions regime.

“These are usually not well-established, well-known companies with a long history of trading. The fact that a company was created right after the invasion and the imposition of sanctions suggests that its sole purpose may be to evade sanctions,” he stated while stressing that merely registering after 2022 is not sufficient grounds for inclusion on the sanctions list.

Strategically Important Central Asia

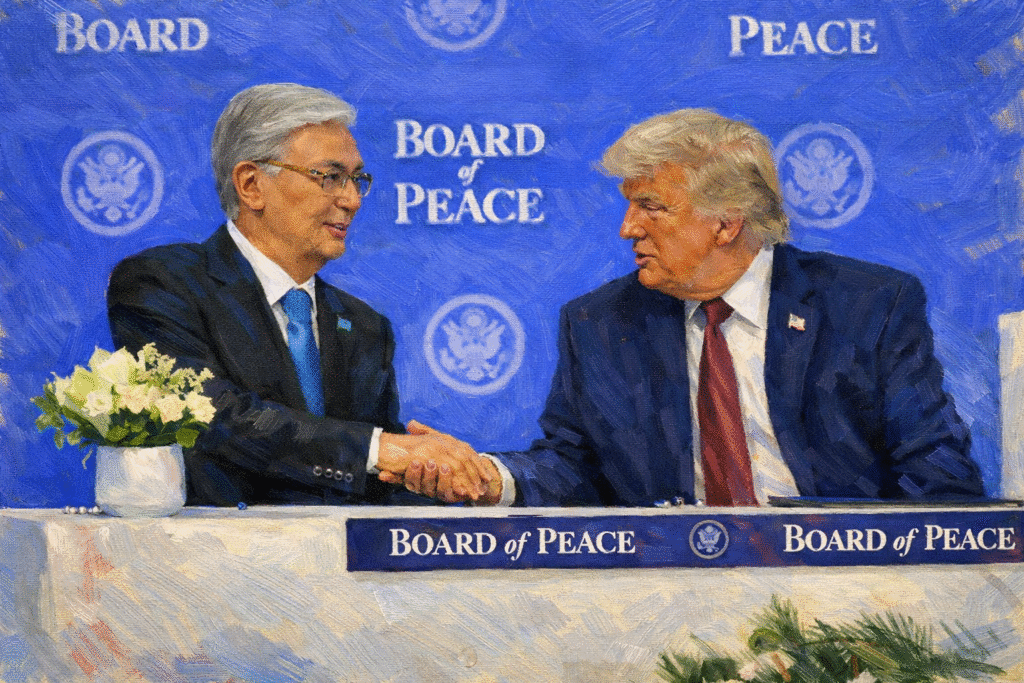

Given the statistics cited by O’Sullivan, there was no pressing need for his fourth personal visit to Kazakhstan. The blacklisting of two Kazakh companies last year went largely unnoticed by the country’s general public. However, his visit highlights the mechanisms of international politics set in motion following Donald Trump’s return to the White House and the opening gambits of his administration, such as his ambitions to buy or seize Greenland and his desire to shift the burden of the war in Ukraine onto Europe.

In the emerging architecture in the new paradigm of global politics, it seems that Central Asian countries are being assigned a special role, and O’Sullivan’s visit is closely tied to these developments.

A confirmation of this growing interest in the region comes from as far afield as Tokyo. Recently, it was announced that Akihisa Nagashima, a special advisor to Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, had embarked on an 11-day tour across the five Central Asian countries which will continue until February 8, with Kazakhstan being the first country on his agenda. Nagashima is also scheduled to visit Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan for high-level discussions aimed at “exchanging views on strengthening” cooperation.

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs explained this interest by noting that Central Asia, a strategically significant region bordering Russia and China, is “rich in resources such as natural gas.” Highly dependent on energy imports, Japan is therefore seeking to strengthen economic ties with the region.

In August 2024, the former Prime Minister of Japan, Fumio Kishida, had planned to visit Central Asia, but the trip was ultimately canceled due to warnings of an increased risk of a major earthquake along Japan’s Pacific coast. Kishida was due to hold the first-ever forum with Central Asian leaders with a view towards adopting a joint statement on “economic cooperation.”

At the same time, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Mishustin also visited Kazakhstan to participate in the Eurasian Intergovernmental Council. Some Russian analysts believe the Kremlin will attempt to prevent Kazakhstan from pivoting toward the West. For instance, Vitaly Danilov, director of the Center for Applied Analysis of International Transformations at RUDN University, noted that Moscow does not fully comprehend Kazakhstan’s intentions.

“We have joint projects aimed at creating a common Eurasian space, we cooperate within the CSTO, and we work on consolidating post-Soviet nations. Yet at the same time, we see Astana moving toward the West, and this policy remains largely inexplicable to the Russian side,” Danilov stated.

It appears that in response to Trump’s reshaping of world politics, the major economies of the so-called ‘Global West’ are increasingly searching for a foothold and new allies in Central Asia.