BISHKEK (TCA) — Moscow is reportedly negotiating sending troops from its CSTO allies — Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan — to monitor the military situation in Syria. The move, if it happens, certainly meets Russia’s political goals but it would bring nothing but headaches to the Central Asian countries, which are still reluctant to sign up to Moscow’s initiative. We are republishing this article by Uran Botobekov on the issue, originally published by The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor:

Moscow wishes to expand its military-political influence in the Middle East by drawing into the war in Syria members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a Russian-led, amorphous military bloc that also includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. On June 22, the chairman of the Defense Committee of the State Duma of Russia and the former commander of the Russian Airborne Forces, Colonel General Vladimir Shamanov, said that Russia was negotiating with Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan to send troops from those countries to Syria. These forces would monitor the military situation on the ground (RIA Novosti, June 22). According to Shamanov, this issue is being worked out with the political and military leadership of the two Central Asian states, but the decision has not yet been taken.

Colonel General Shamanov’s statement seems to indicate that Russian President Vladimir Putin is trying to expand the number of allied governments active in Syria that would support Moscow’s military actions there. Today, Iran is the only country that is more or less a staunch ally of Russia in Syria and the broader Middle East. Indeed, Tehran plays one of the key roles in supporting the embattled political regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

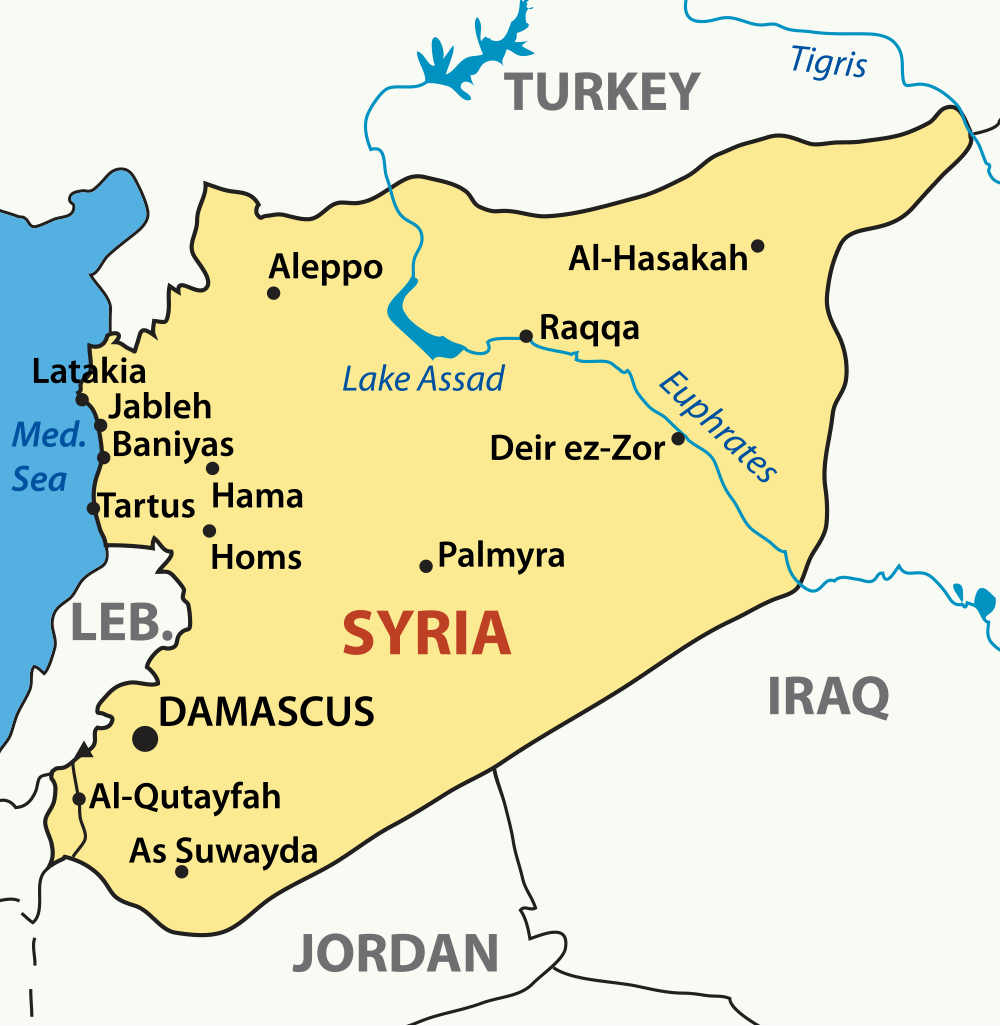

On May 3–4, during the fourth international meeting of the so-called “Astana talks,” dedicated to negotiating a settlement of the war in Syria and organized upon Moscow’s initiative (see EDM, May 4), representatives of the guarantor countries in Syria (Russia, Iran and Turkey) signed a memorandum on the creation of four “de-escalation zones” (Mid.ru, May 6). The agreement provided for sending military forces from guarantor countries to the de-escalation zones in order to monitor the ceasefire regime. Ankara, Moscow and Tehran confirmed they were ready to send their military observers to Syria.

Following the conclusion of the aforementioned talks in Astana, the Russian president’s special representative for Syria, Alexander Lavrentiev, said that the participation of military observers from other countries was possible, but only on the basis of consensus and with the consent of all three guarantor countries (RIA Novosti, May 5). Iran and Turkey immediately agreed with Moscow’s offer to expand the number of observer states. And the June statement by Russian parliamentarian Shamanov suggests Russia has begun to take tangible diplomatic steps toward this end.

On the same day as Shamanov made his announcement, İbrahim Kalın, the Turkish president’s special representative on Syria, himself revealed that Russia had proposed deploying military observers from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to the de-escalation zones in Syria (Haberturk.com, June 22). The Turkish side expects that this issue will be included for discussion during the fifth international meeting on the settlement of the Syrian conflict, which will be held in Astana later in July. Evidently, Russia is trying to strengthen its position in the Middle East by drawing on the support of two of its former protectorates, which themselves consider Russia their strategic partner. Illustratively, during a recent meeting with Putin, Kyrgyzstan’s President Almazbek Atambaev stressed that he could not imagine a future for his country without Russia (Sputnik.kg, June 20).

However, officials in Bishkek and Astana have been in no hurry to confirm the announcements made by the high-ranking Russian and Turkish officials. Rather, Kyrgyzstani President Atambaev noted, “To send troops to Syria, first a unanimous decision of all members of the CSTO is necessary; second, a resolution of the UN [United Nations] is necessary; third, the parliament of the country has to agree; fourth, if such a question arises, Kyrgyzstan has to raise non-active armed forces, meaning interested individuals from among the professional soldiers as well as officers who could accumulate experience there and earn money” (24.kg, June 24).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan also issued an official statement undercutting Shamanov’s and Kalın’s declarations: “Astana is not negotiating with anybody to send Kazakhstani servicemen to Syria” (Mfa.kz, June 23). For Kazakhstan, a crucially important condition for sending its peacekeepers to any hotspot around the world is the existence of a resolution and mandate from the UN Security Council.

Both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have been quite careful in their reference to the issue of sending troops to Syria. It is certainly possible to expect that Russia will try to achieve its goal by calling on and deploying units of the CSTO’s Collective Rapid Reaction Force (CRRF), which numbers some 20,000 troops from the alliance’s member states (Odkb-csto.org, June 2009). However, Moscow’s desire to obtain military support in the Middle East from its Central Asian CSTO allies is a difficult task.

First of all, the authorities of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are convinced that sending troops to Syria, where their service members could die in a “foreign war,” would greatly complicate the internal political situations of these Central Asian republics. Second, if the two countries in fact intend to send troops to Syria, they will have to obtain permission from their national parliaments—an extremely unlikely outcome particularly for Kyrgyzstan in the run-up to presidential elections, scheduled for October 2017. Third, the religious factor also plays an important role. It is widely known in Central Asia and across the Muslim World that Russia is supporting the Alawite regime of Bashar al-Assad, who belongs to the Shiite branch of Islam, while the armed Syrian opposition represents Sunnis. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, meanwhile, are Sunnis. Moreover, the religious leaders of both countries have repeatedly expressed discontent with Russia’s military operations in Syria (The Diplomat, October 18, 2016). By sending troops to the Middle East, the authorities of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan could lose the support of their Muslim believers.

Moscow’s supposed desire to enlist the support of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan for the Russian operation in Syria should be viewed as a PR campaign directed primarily at the West. Western politicians and the media have repeatedly accused the Russian military of fighting in the Syrian civil war on the side of al-Assad’s army. By inviting his Central Asian allies to enter the conflict, President Putin wants to announce to the world that Russia is still an international force to be reckoned with.