On a gloomy winter’s day, The Times of Central Asia visited the Silk Roads Exhibition at the British Museum. The sight of a significant queue wrapped around the museum for entry was startling. Once inside, the exhibit thronged with visitors snaking their way to peruse artifacts arranged by region and era. Concerned about blocking display views as you read descriptions? No need to worry — thick guidebooks with full narratives greeted you at the entrance to borrow during your visit.

The exhibition envisions the Silk Road as the beating heart of the ancient world, with arteries stretching across seas, mountains, and deserts. With over 300 artifacts spread across five geographical zones, it can be hard to know where to start. I observed a nearby gentleman in tweed who offered a simple tip: start with a place that interests you and go from there. Then I overheard that he was going to Cairo.

New partnerships with Uzbekistan’s Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) and Tajikistan’s museums had seen fresh items loaned to the exhibit. These collaborations highlight Central Asia’s important role in this sweeping narrative, helping to connect the dots in this continent-spanning story.

Immersed in the culture and history, I couldn’t help but wonder — what did the audience think? After a few unsuccessful attempts, I spoke with an English visitor named Georgie Bennett.

Georgie Bennett visiting the Silk Roads Exhibition; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

TCA: What drew you here today?

I think the thing for me is I have a really poor knowledge and understanding of this bit of history. So, I heard the exhibition was on and some of my friends already booked tickets, I said yes, I’ll absolutely come along because… I wanted to learn more.

TCA: What’s the one item that’s caught your eye the most?

I really like the story of the silk princess; it was a very humanizing story about this lady who’s newly married and brings the knowledge of how to make silk to her husband’s kingdom… I feel like I’ve learned so much. I’m enjoying it, though I almost wish I had a notebook and pen because I’m getting a general impression without knowing any of the details.

Charred wooden door panel from Kafir Kala, near Samarkand, Uzbekistan, circa AD 500, on loan from the State Museum reserve

The Times of Central Asia also spoke to one of the curators, Luk Yu-Ping to delve deeper into the Silk Road experience.

TCA: Globalism is considered a modern concept of interconnectivity, but looking at the vast connections and influence within the Silk Road Exhibition it’s implied that this concept may have been prevalent in the past along these trade routes. Could you expand on this?

This exhibition highlights the movement of people, objects, and ideas across Asia, Africa, and Europe during the period 500 to 1000 CE. The focus is not only on trade but also other ways of contact and exchange. Audiences might be surprised by how connected Afro-Eurasia was already during this period, centuries before the globalized world we live in today. It reminds us that humanity has a long history of making connections across different boundaries. While the span, speeds, and methods have changed, the act of connecting will continue to shape our present and future.

TCA: A highlight of the exhibition was its focus on how cultures mixed and exchanged ideas — that diversity and tolerance encouraged innovation. Which particular artifacts embody this concept?

A good example is ceramic production in Tang China and the Islamic world. The exhibition displays a rare blue-and-white dish, one of three from a 9th-century shipwreck found off the coast of Indonesia. It is believed that the ship was on its return journey from the ports of southern China to the Arabian Peninsula or Persian Gulf. The color palette and decoration on the dish are unusual for Tang Chinese ceramics. It shows potters in China experimenting with cobalt blue, probably imported from Iran, to cater to an export market.

At the same time, as more Chinese ceramics reached the Islamic world, local potters started to imitate the shapes and glazed white surfaces of these imported wares. This led to the development of an opaque white coating, which may be decorated with designs in cobalt blue pigment, also probably sourced from Iran, as seen in an example from Basra, Iraq. These wares demonstrate the two-way exchange between Chinese and Islamic ceramics.

Zoroastrian clay ossuary, Mullah Kurgan, Samarkand region, Uzbekistan, circa AD 600-700, on loan from the State Museum reserve; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

TCA: The Silk Roads were not only about trade but also about cultural transformation. Religion was another product that was imported and carried along these routes. When it comes to Central Asia, is there a particular golden era or area linked with a religion or religious change?

The Sogdians, whose homeland was in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, practiced a local form of Zoroastrianism. The Zoroastrian religious iconography in Sogdiana was particularly rich and imaginative. The exhibition features a well-preserved ossuary from the Samarkand region, depicting Zoroastrian priests facing a fire altar. In the early 8th century, Sogdiana was conquered by Arab forces, and Islam spread to Central Asia.

New forms of visual and material culture subsequently developed. For instance, the exhibition shows an architectural stucco panel from Samarkand during the Samanid period, decorated with a medallion. This form of abstract, geometric design derived from vegetal motifs became a distinctive feature in Islamic art and can be found in many sites across the Islamic world, suggesting the movement of artisans and model designs.

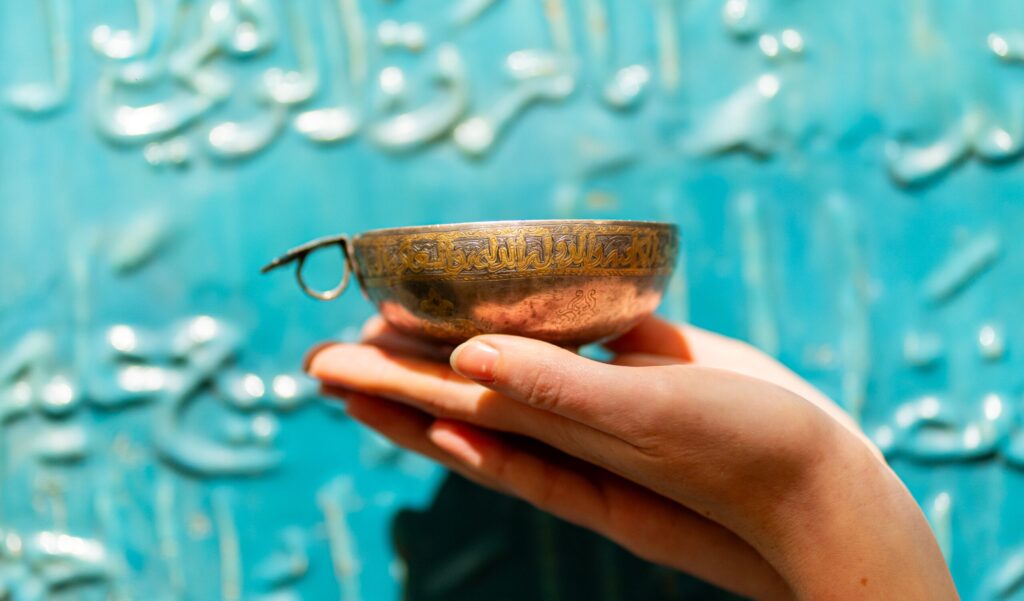

Gift shop treasures; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

I love visiting museum stores for unique finds as there’s always something fun to grab, and the Silk Roads was no exception, I found funky socks, fridge magnets, and keychains. They also offer stunning replicas of exhibition pieces — perfect for collectors or as standout gifts for loved ones – and fitting for an Exhibition devoted to a route that was the heartbeat of trade in the ancient world.

The exhibition runs till February 23rd, 2025, in The Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery at the British Museum. Grab your tickets to an unforgettable cultural adventure and find out more here.