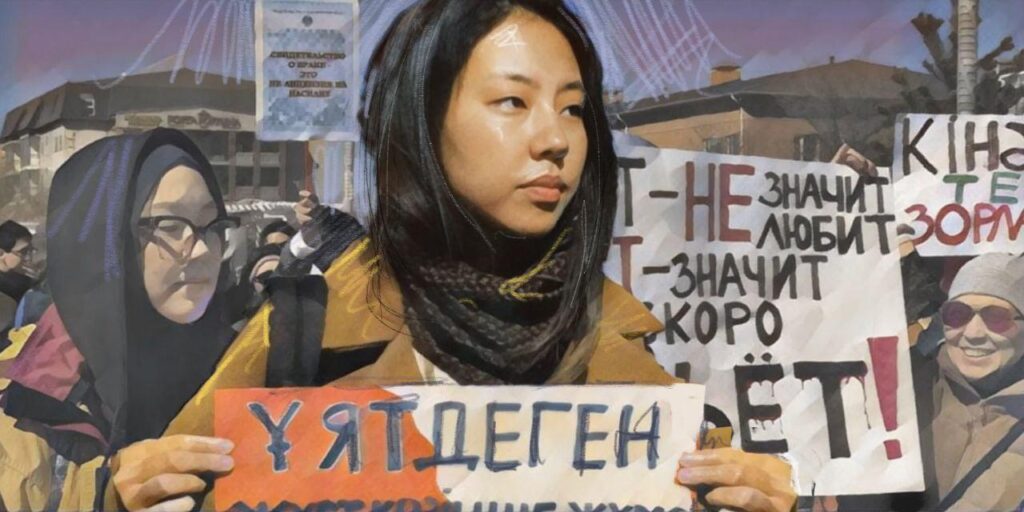

In the spring of 2024, the televised murder trial of Kuandyk Bishimbayev, Kazakhstan’s former Minister of the National Economy, captivated viewers across the country. Bishimbayev was found guilty of the brutal murder of his wife, Saltanat Nukenova, in a restaurant in Astana, and sentenced to 24 years in prison. Comparisons to the O.J. Simpson trial of 1995 were inevitable. Both trials involved a prominent figure — in this case, a politician previously pardoned by President Nursultan Nazarbayev after serving time for corruption — a victim who had endured domestic abuse, and a massive viewership. Bishimbayev’s trial underscored public fascination with the case, driven not only by its reality TV appeal but by a growing awareness of deeply ingrained gender inequities, particularly regarding the societal expectations placed on Kazakh women within marriage. The trial’s timing occurred shortly before — and perhaps by no coincidence — new legislation was signed by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev on April 15, 2024, amending laws to protect the rights and safety of women and children. However, critics noted an omission: a clear, targeted focus on preventing domestic violence.

Two Kazakh women, who shared their stories with The Times of Central Asia, revealed the extent to which domestic violence remains embedded in Kazakh society. Rayana, from Astana, and Aliya, a Kazakh student in New York City, have never met, yet their stories echo shared challenges and hopes for change in their home country.

Rayana, a beauty industry professional in her mid-twenties, reflected on her brief and tumultuous marriage, which began when she was 23. “I loved my husband, but felt it was too early to marry. We married just four months after meeting, and within a month of living together, I wanted a divorce. He was unfaithful and violent.”

When Rayana sought help from her mother-in-law, she was told that her mother-in-law had also been a victim of domestic violence and that she, too, must learn to endure it. “It is worth mentioning that in Kazakhstan the north is very different from the south,” Rayana added. “I’m a northerner, he’s a southerner. I had never experienced abuse before, and then for the first time, I felt a panic attack, which I still live with. In the south, people adhere more to traditions and have a negative attitude towards divorce and washing their dirty linen in public. Women keep silent about domestic violence. I can’t say anything about his family’s attitude. I still don’t fully understand.”

Having grown up around domestic violence, she believes that one in two families is affected by it. After separating, Rayana’s family offered her support, while her in-laws disapproved, even throwing out her belongings.

Rayana’s life since then, however, has vastly improved. “I have been working in the beauty industry for a long time. In our field, at least, climbing the career ladder is not difficult. My first supervisor helped me a lot. He spoke fondly of his wife and cared about his female employees. This gives us faith that there are good men in Kazakhstan. Now, I provide consulting services for beauty salons and barbershops. In addition to organizing events, we are currently preparing a women’s forum for 500 people with speakers represented by successful women who inspire us. I’m not ready to start my own business yet, but I feel comfortable with hiring and I feel like I can help a lot of people here. There is already a lot of evil and violence, so we are trying to be kinder and more united.”

Now financially independent, Rayana is optimistic about the recent legal reforms, but wary of the road ahead. “Just because the constitution says you can’t beat a woman, men don’t stop,” she noted. “Our silence and fear are passed down to our daughters. This chain needs to be broken now.”

Having taken a break from entering into a new relationship, Rayana remains hopeful about remarrying and building a family in the future. “I hope to meet a man whose ego can embrace the success of his partner.”

Reflecting on the Bishimbayev trial and recent women’s rights law amendments, Rayana has thought carefully about what is needed to bring about real improvements in the lives of women and girls in Kazakhstan.

“Of course, the brutal murder of Saltanat Nukenova and the way her family fought for justice opened the eyes of the people. I believe that the educational program should include an elective on financial literacy. Quite a few women remain in abusive relationships due to financial dependence on their husbands. I urge parents to explain to their children from an early age what is bad and what is good, and if they are in trouble, there are always people who will help them. I hope the government will pay more attention to support centers for victims of domestic violence. I have experienced domestic violence, infidelity, and divorce. Today, I dictate the rules of my own life. I am surrounded by kind and successful people, and my past has taught me a lot and made me stronger.”

Aliya, 28, who moved from Kazakhstan to the United States six years ago and is now a student in New York City, has noticed significant differences in the support available to women in each country. “I experienced domestic violence here in the States when I was 24,” she said. “I lived in fear and constant anxiety. If I’d known that a simple protection order could help, I would have sought help sooner. I was shocked at how easy it was to get that protection and finally feel safe. This experience has given me a unique perspective on women’s rights issues in both countries. I understand deeply how difficult it is for many women in Kazakhstan who may not have the same option. I didn’t realize I was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and panic attacks until a therapist reached out to me after my police visit. I didn’t know I needed help as I’m from a country where mental health is ignored.”

Aliya believes that Kazakhstan’s patriarchal norms perpetuate abuse, with survivors often blamed for their situations, stigmatized if they divorce, and pressured to stay in unsafe marriages. “In Kazakh society, divorced women — especially mothers — face significant stigma, making it harder to leave abusive relationships.”

Reflecting on the Bishimbayev case, Aliya described the sentence as a small step in a long journey. “Bishimbayev represents all abusive men to me. His wife was brutally beaten for eight hours in a restaurant filled with staff who likely heard her cries for help, but chose to ignore them. I’m not fully satisfied with his 24-year sentence. His status as a political figure made it even harder for Saltanat to seek help, as men with money and power could easily influence the police and courts.”

Both women agree on the need for change at every level — from stronger laws to shifts in cultural attitudes. Rayana advocates for financial literacy education for girls, to reduce financial dependence on abusive partners, while Aliya emphasizes the need to educate boys and men about equality and respect. “Parents, teachers, and leaders should emphasize that no one has the right to harm others,” Aliya noted, “and girls should feel empowered and valued in society.”

Despite their challenges, Rayana and Aliya remain hopeful. “Kazakhstan is at a critical turning point,” Aliya remarked. “There’s a rising awareness among the younger generation, and recent legislative changes show promise. However, true progress will require both structural changes and a shift in cultural attitudes to ensure that women are treated with respect and dignity, free from fear and stigma.”