Critical minerals are essential components in many of today’s rapidly growing energy technologies. From lithium in electric vehicle batteries, to copper used in wind turbines and electricity networks, these minerals are at the heart of the green transition. The demand for these minerals will increase as clean-energy technologies continue to develop and become even more widely adopted.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts a significant uptick in mineral requirements for clean energy technologies. According to its Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), the world’s total mineral demand could quadruple by 2040. Electric vehicles and battery storage are expected to account for about half of this growth over the next two decades.

A few major producers dominate the global market

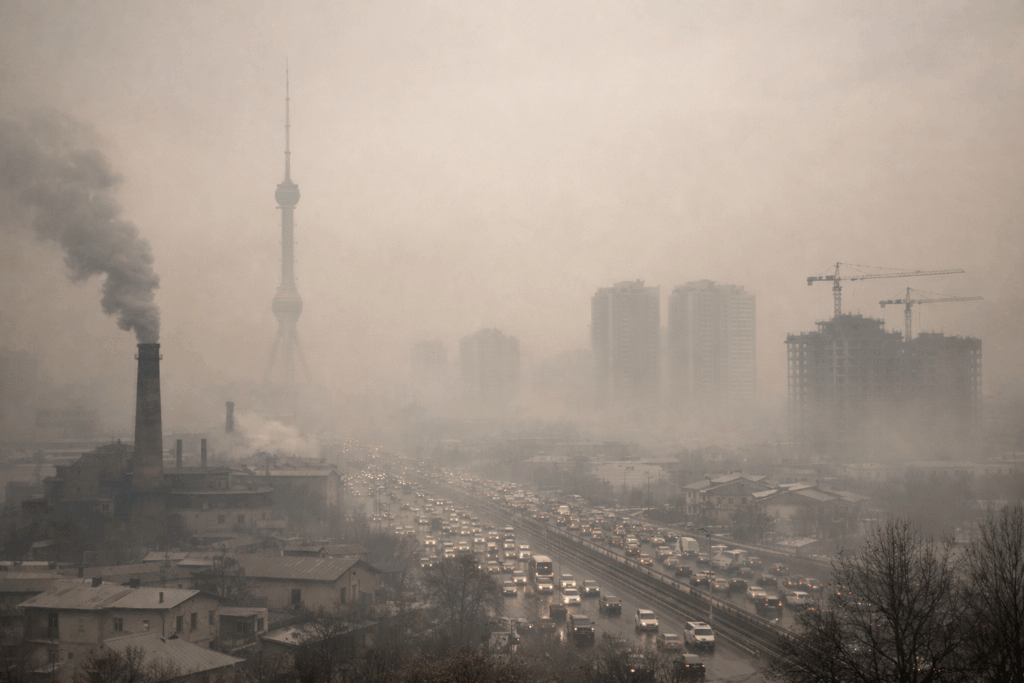

Problematically, the global market for critical minerals is dominated by just a few key players. China controls a significant portion of overall worldwide production, not to mention 85% of the processing capacity needed to refine these minerals for manufacturing purposes. China’s dominance extends to lithium, graphite, rare earth elements and cobalt, which are all essential for clean energy technologies.

Russia also holds considerable weight in the resource-extraction sector. For example, it controls 43% of the palladium market and a quarter of vanadium production. These minerals have wide-ranging applications, with palladium used in catalytic converters and vanadium in batteries.

The United States is heavily reliant on mineral imports from China. This dependence poses significant economic and security risks as any supply-chain disruption could have far-reaching impacts. As a result, the U.S. has initiated the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) and the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP). The PGII is a shared G7 commitment, while the MSP drives co-operation of 13 countries and the European Union (EU). They both aim to catalyse public and private investment in responsible global supply chains of critical minerals.

Fortunately, Central Asia is emerging as a key player in the global critical minerals landscape. The region is perhaps best noted for its substantial reserves of uranium, of which it is the world’s largest supplier. Less known is the fact that the region also holds 38.6% of global manganese ore reserves, 30.07% of chromium, 20% of lead, 12.6% of zinc and 8.7% of titanium, as well as significant reserves of other critical materials.

Eyes turn to Kazakhstan’s special contribution

While all of Central Asia is rich in these minerals, Kazakhstan is increasingly noticed as the stand-out performer. Kazakhstan is perhaps best known as the global leader in uranium production. It has the world’s largest reserves of this metal, and has been the world’s top producer for several years. Uranium is necessary for the global nuclear energy supply chain, and Kazakhstan has implemented advanced recovery techniques, making the extraction process both efficient and environmentally friendly.

Kazakhstan also has significant potential in rare earth elements, and is one of the world’s largest producers of chromium (used primarily in producing stainless steel and other alloys) with one of the world’s largest deposits and significant mining operations in the northwest regions. The country is also a major producer of copper, which is essential for electrical equipment, construction and renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels and wind turbines.

In addition, Kazakhstan also has significant reserves of zinc, which prevents corrosion in steel, and lead, which is needed for batteries, as well as bauxite, which is the primary ore for aluminium production. Kazakhstan’s strategy in the critical minerals sector involves not only extracting these valuable resources, but also developing downstream processing industries to add value and diversify its economy.

The West’s strategic pivot to Central Asia’s minerals

All the above-mentioned minerals are essential for a wide range of technologies, from renewable energy to advanced electronics. Today, however, China is the main destination for most of Central Asia’s critical minerals. Chinese companies hold well over half of the mineral-extraction licences in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, for instance. The challenge for Central Asia and the West is to find ways of managing the former’s resource wealth while reducing geopolitical risks for both sides.

The renewed American interest in Central Asia was highlighted when President Joe Biden proposed the “C5+1 Critical Minerals Dialogue” in September last year. Signalling a strategic American pivot towards the region, which is now also shared by Europe, the initiative aims to develop Central Asia’s mineral resources in a more equitable way.

The Central Asian countries, with their vast reserves, would benefit from diversifying their supply chains and reducing their dependence on China as an export destination. This desire complements Western strategic geo-economic initiatives underscored by reports from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and other international financial institutions, as well as by American policy instruments, such as the Agency for International Development. Central Asian countries also understand that the age of hydrocarbons will come to an end, and the transition to renewables industry is critical for their economic vitality.

The U.S. strategic interest in Central Asia is multifaceted. It includes the construction of a prosperous, more stable region that will be free to pursue, on its own terms and with a variety of partners, its own political, economic and security interests. This policy goal requires connecting the region to global markets and promoting international investment. American investment in Central Asia’s mining and processing capabilities should include technology transfers and sharing of expertise.

Such investments could help Central Asian countries develop their mineral resources sustainably and responsibly, while also creating opportunities for U.S. businesses. By fostering co-operation and investing in the region’s capabilities, the U.S. can help shape a more diversified and resilient global supply chain for much-needed critical minerals.

The global push to develop these resources presents a unique opportunity to reset Central Asia’s economy. This shift is not only an economic transformation but also a strategic manoeuvre that could break China’s monopoly on future technology production. Central Asia, with its vast reserves of critical minerals, is poised to play a key role in the global supply chain for emerging technologies. However, the extraction and processing of these minerals must be done in a sustainable and responsible manner. The U.S. and its allies have a great interest in promoting sustainable mineral extraction practices.