In June 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin made a chilling declaration at the St. Petersburg Economic Forum: ‘There’s an old rule – wherever a Russian soldier sets foot, that’s ours.’ Far from a metaphor, this line encapsulated the Kremlin’s evolving foreign policy doctrine. It is a doctrine where military occupation becomes territorial acquisition, and where presence becomes ownership.

But this ideology did not appear overnight. It has been systematically constructed through years of rhetorical groundwork, beginning with Putin’s 2014 remark at the Seliger Youth Forum: ‘Nursultan Nazarbayev created a state on territory where there had never been a state. The Kazakhs never had statehood.’ In 2021, speaking at a Moscow press conference, Putin went further, describing Kazakhstan as ‘a Russian-speaking country in the full sense of the word.’

These comments expose a geopolitical logic that fuses cultural affinity, historical denial, and military dominance. They form the pillars of what scholars like Marlene Laruelle and Timothy Snyder describe as Russia’s ‘narrative imperialism’: the use of historical revisionism and linguistic hegemony to delegitimize the sovereignty of neighboring states.

Nowhere is this doctrine more clearly manifest than in the cases of Ukraine and Kazakhstan. In Ukraine, the justification for annexing Crimea in 2014 and launching a full-scale invasion in 2022 relied heavily on the protection of Russian-speaking populations and claims of historical unity. In Kazakhstan, the groundwork is rhetorical – but eerily similar.

In 2014, Putin reversed Nikita Khrushchev’s legacy by annexing Crimea, which Khrushchev had transferred to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954. At the same time, Kremlin-aligned voices began revisiting Khrushchev’s failed plan to remove five northern regions of Kazakhstan to form Russian ‘Virgin Lands’.

This was not a mere administrative reform: the plan involved transferring the fertile, Slavic-populated regions of Akmolinsk, Kostanay, Pavlodar, North Kazakhstan, and East Kazakhstan regions from the Kazakh SSR to the Russian SFSR. The objective was both economic and political — to consolidate agricultural output under Moscow’s direct jurisdiction and reduce the autonomy of the Kazakh republic by undermining its territorial coherence and ethnic composition.

These areas were the backbone of Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands Campaign and held great strategic value. The proposal sparked resistance from within the Kazakh leadership, most notably from Premier Zhumabek Tashenov, who openly opposed the Kremlin’s intentions. As a result of his opposition, he was dismissed from his position, but he succeeded in preserving Kazakh territorial integrity.

These northern regions, like Crimea, are demographically significant: they are home to a large ethnic Russian population, many of whom speak only Russian, consume Russian media, and express nostalgia for Soviet-era unity. Cities like Petropavlovsk, where Russians still outnumber Kazakhs, mirror the pre-2014 situation in Donetsk and Luhansk.

In 2023, a group calling itself the ‘People’s Council of Workers’ in Petropavlovsk released a video declaring independence based on the 1937 Constitution of the Kazakh SSR. Prosecuted for inciting separatism, they nonetheless reflected growing latent support for Russian intervention.

Even earlier, in 2014, Russian ultra-nationalist Eduard Limonov made headlines by urging Russia to annex Northern Kazakhstan during a perceived political vacuum. In a Facebook post, he wrote: ‘I hope that part of Ukraine will go to Russia, if we do not yawn, and northern Kazakhstan too — we can get our Russian cities back into Russia in the moment between governments in Kazakhstan.’

His call triggered a diplomatic protest from the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which emphasized Kazakhstan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. While dismissed as a fringe voice, Limonov’s rhetoric mirrored the Kremlin’s growing tendency to conflate Russian ethnicity and language with sovereign entitlement.

Limonov was not alone. Duma member Denis Maydanov publicly described regions east of the Dnipro River and northern Kazakhstan as ‘primordially Russian.’ State media host Vladimir Solovyov has repeatedly advocated for strikes on Europe and ridiculed Kazakhstan’s efforts to assert its own national language. In 2020, Duma members declared that ‘Northern Kazakhstan is a gift from Russia,’ further escalating tensions.

This convergence is not accidental. It is the result of long-term settler colonial policy. Just as Zionist strategists in Palestine targeted fertile Palestinian lands for acquisition, Soviet planners in the 1950s chose the rich black soils of northern Kazakhstan as the site for Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands Campaign. The campaign’s goal was not only to feed Soviet cities, but to anchor Slavic demographic dominance.

Over 43 million hectares were taken under the guise of ‘virgin land,’ despite being inhabited or used by Kazakh nomadic communities. Both cases reveal the same logic: that land becomes ‘productive’ only when repurposed through settler frameworks. The Zionist motto of ‘making the desert bloom’ has its Soviet counterpart in the Virgin Lands campaign, where productivity became a means of erasure. As historian Kate Brown writes: ‘Virgin Lands were not empty. They were made to appear so through cartography, statistics, and ideology.’

Putin’s 2025 proclamation that Russian military presence confers territorial legitimacy is merely the latest iteration of this logic. As with any neo-colonial or neo-imperialist power in the modern century, everything begins not with invasion, but with information control and narrative seeding. In the case of Ukraine, the groundwork was laid as early as the mid-2000s.

When I was studying at Moscow State University, it was not uncommon to hear members of the academic elite openly express frustration with the political trajectories of Georgia and Ukraine. This sentiment was echoed and amplified by Russia’s most powerful propaganda apparatus: its state-controlled television. These channels and political talk shows relentlessly pushed disinformation and revisionist history, preparing the Russian public psychologically for the eventual invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 and again in 2022.

A similar rhetorical pattern has been emerging in relation to Kazakhstan since the mid-2010s, as narratives around ‘Russophobia,’ ‘protection of Russian speakers,’ and historical territorial claims have become increasingly common in Kremlin-aligned discourse. This is not accidental — it is the same imperial script, playing out once again. Like the Zionists before 1948, and like the Soviet strategists before him, Putin treats cultural proximity, military capability, and historical manipulation as tools to reshape borders and subvert sovereignty. His empire is built not only with tanks, but with narratives.

Kazakhstan, like Ukraine, now stands at a crossroads. Putin’s statement about the sanctity of Russian military presence is particularly alarming given that Russia maintains its largest military base abroad in Tajikistan. The 201st Military Base, with an estimated 6,000–7,000 troops, operates in Dushanbe and Bokhtar and serves as the Kremlin’s principal outpost in Central Asia. While Kazakhstan does not host a large-scale base of this nature, it does lease the Baikonur Cosmodrome to Russia until 2050, and hosts Russian-operated radar systems and CSTO-linked infrastructure.

These facts are not benign: they reflect a triad of mechanisms through which Russia pursues its neo-imperial project of historical revisionism and territorial expansion. First, the Kremlin actively re-writes history, denying the legitimacy of its neighbors’ statehood – as seen in claims about Kazakhstan’s alleged lack of historic sovereignty and the illegitimacy of Ukraine’s post-Soviet borders.

Second, it exploits citizenship law as a geopolitical tool. Russian legislation grants Moscow the legal right to intervene abroad to protect its citizens. By encouraging Russian populations in former Soviet republics to retain or regain Russian passports, the Kremlin effectively lays a juridical pretext for military engagement. This logic was central in Crimea and is increasingly visible in regions of Kazakhstan with high numbers of dual passport holders.

Third, Russia uses its military bases and peacekeeping mechanisms — like the CSTO — to maintain a physical and psychological presence. The very infrastructure that claims to defend regional stability can, under Putin’s doctrine, serve as a foothold for annexation under the guise of protection or peacekeeping.

Together, these steps comprise a sophisticated playbook: one that begins with myth-making, continues through identity manipulation, and culminates in occupation. Kazakhstan has no nuclear deterrent, having voluntarily dismantled the world’s fourth-largest arsenal in the 1990s. Its military infrastructure near the Russian border is minimal.

And yet, it faces the same creeping logic of imperial incorporation. Language, land, and memory are weaponized in the service of expansion.

As Kazakh analyst Gaziz Abishev warns: ‘If Russia supports separatism and succeeds, it will lose Kazakhstan forever. And then, foreign military bases – Chinese or Western – will line the Russian border.’

The irony is sharp: a state dismissed by Putin as having ‘never had statehood’ may one day mark the final rupture in the Russian imperial dream. In this moment of creeping authoritarianism and regional vulnerability, the question must be asked: with so many red flags waving — from historical revisionism to military presence and legal pretexts for intervention — are the Central Asian states, and Kazakhstan in particular, truly prepared to face what may be coming?

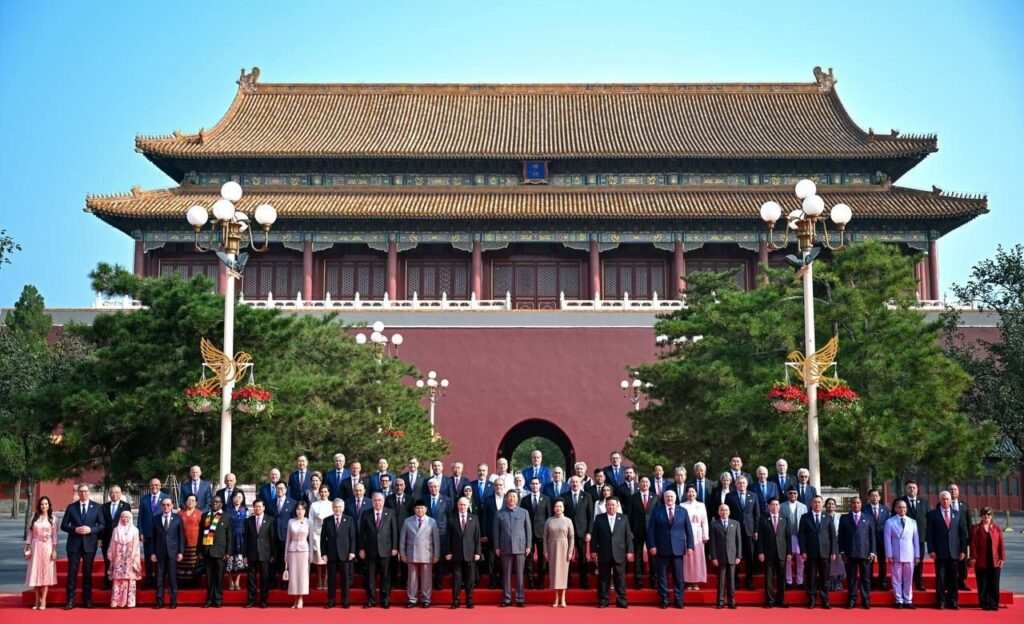

Will China, their powerful neighbor and supposed strategic partner, stand by them when sovereignty is threatened? Or will it, like so many others today in the face of global injustices and ongoing atrocities, limit its response to empty statements and silent complicity?

***

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publication, its affiliates, or any other organizations mentioned.