According to the new research paper “Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation in Central Asia” released by the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB), almost 10 million people, or 14% of the population, have poor access to safe drinking water in Central Asia.

Water withdrawals for drinking and domestic use increased twofold to reach 8.6 km3 between 1994 and 2020. Investment in its supply infrastructure, however, failed to match growth in consumption. It is estimated that as much as 80% of the region’s water and sanitation equipment is no longer fit for purpose. In addition, physical and commercial water losses in distribution networks can be as high as 55%.

The EDB research paper highlights a clear lack of financial support for plans adopted by Central Asia to develop the sector, and forecasts a deficit of over $12 billion, or around $2 billion per year, between 2025-30.

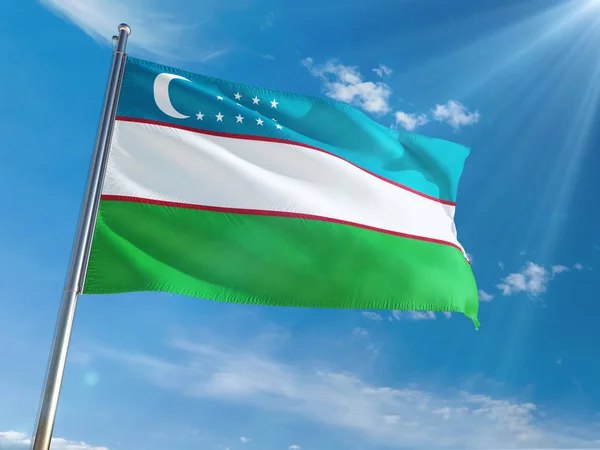

The largest shortfall is expected in Uzbekistan, estimated at $826 million per year, or almost $5 billion between 2025–30. A large shortfall is also projected for Kazakhstan at $700 million per year, or $4.2 billion from 2025–30. In Tajikistan, the shortfall will also be significant, given the size of the country’s economy, reaching $209 million per year, or more than $1.2 billion from 2025–30.

To address the issue, the EDB paper outlines three solutions that could help Central Asian countries raise the required investment capital.

First, the funding gap can be reduced by attracting finance from international financial institutions (IFIs), multilateral development banks, and development agencies. The water and sanitation sector in Central Asia currently accounts for only 6% of total IFI-approved sovereign funding provided to the region CA, with 147 projects valued at $4 billion (out of a total of $67.5 billion) completed from 2008–2023. Concerted efforts are required to improve the appeal of investment in the sector to attract more active involvement by IFIs. With the emergence of a new, favourable institutional environment and the arrival of private players, the potential of the corporate investment becomes significant.

Secondly, to attract the much-needed finance from private investors and major players, the CA water and sanitation sector must not only modify the ownership and governance structure, but also create conditions conducive to the effective development of market relations. Regarding the above, Evgeny Vinokurov, EDB Chief Economist, stated, “The strengthening of public-private partnership institutions can be of great help. With PPPs active in the water sector, state and private structures will be able to cooperate in a more productive fashion. Expansion of the water sector services market will boost competitiveness and improve the operating efficiency of individual companies. The presence of strong PPP institutions is likely to encourage private operators to join water sector projects. The advent of private players will help the CA countries to attract investments and gain access to innovations, technologies, and experience required to modernise the sector.”

Thirdly, improving the tariff system is becoming increasingly compelling. Water tariffs in the region are extremely low and could therefore be raised to improve the financial sustainability of water and sanitation companies, and in turn, stimulate investment in developing the infrastructure and improving the quality of services. The CA countries can also delegate their tariff approval and review functions to companies operating in the sector, with control functions vested in local government bodies or independent regulatory bodies. International best practices illustrate the importance to water and sanitation companies in retaining state support in the form of subsidies and soft loans, as well as preserving targeted subsidies for low-income and socially disadvantaged groups of the population.