Nuclear power plants currently operate in only 32 countries in the world. Kazakhstan seems poised to join their ranks in the near future; but what does this shift mean for the energy-rich Central Asian nation?

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan has been a strong advocate for nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament. Astana not only eliminated its nuclear arsenal, which was one of the largest in the world at the time, but also closed the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, where the Soviet Union conducted more than 450 nuclear tests over 40 years.

Thousands of people in Kazakhstan experienced birth defects and cancer linked to nuclear testing. This history makes the construction of a nuclear power plant in the former Soviet republic a particularly sensitive issue. Nevertheless, a majority of the population in Kazakhstan is expected to support building a nuclear facility in the national referendum scheduled for October 6. But what comes after the vote?

If the citizens of Kazakhstan approve the government’s plans to go nuclear, the country might get its first nuclear power plant no earlier than 2035. In the meantime, Astana will have to find a strategic partner to participate in the development of the facility. Building and operation a nuclear power plant requires advanced technology, engineering expertise, and rigorous safety standards – areas where Kazakhstan currently lacks experience.

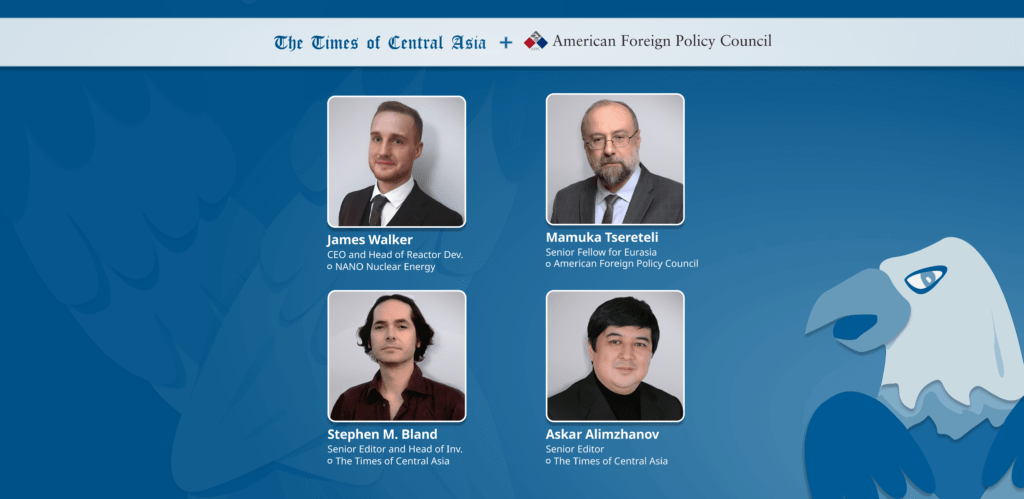

“As a result, the country will likely need to rely on international partners to design, build, and possibly even operate its first nuclear power plant,” said James Walker, CEO and Head of Reactor Development at NANO Nuclear Energy, in an interview with The Times of Central Asia.

Although most policymakers in Kazakhstan would like Western companies to build a nuclear power plant in Ulken, on the western shore of Lake Balkhash, at this point the Russian State Nuclear Energy Corporation Rosatom seems to have the best chance of playing a key role in the project. In Walker’s view, Russia has a long history of cooperation with Kazakhstan in the nuclear sector and could be a logical partner, especially given its extensive experience in building and operating nuclear power plants in other countries.

“Rosatom has been actively involved in Kazakhstan’s nuclear sector for years, including uranium mining and nuclear fuel cycle activities. This established presence, coupled with Russia’s geopolitical influence in Central Asia, makes Rosatom a strong contender,” stressed the CEO of NANO Nuclear Energy, pointing out that Chinese corporations are also very interested in the potential construction of the first Kazakh nuclear power plant.

Indeed, according to reports, the China National Nuclear Corporation offered to build a 1.2 GW nuclear power plant unit in Kazakhstan for $2.8 billion, with the construction taking five years. Another candidate for the project is South Korea’s Korea Electric Power Corporation. The largest electric utility in the East Asian nation reportedly proposed building a water-cooled power reactor –using water as a coolant to transfer heat away from the core.

Walker, however, argues that while South Korea has a competitive edge due to its reputation for building cost-effective and high-quality nuclear reactors, such as those in the United Arab Emirates, it lacks the deep geopolitical ties to Kazakhstan that Russia and China possess.

“This may make Seoul a less likely candidate, unless Kazakhstan seeks to diversify its energy partnerships,” Walker emphasized, claiming that energy security and diversification are major reasons why Astana is pushing for the construction of a nuclear power plant.

As he sees it, developing a robust nuclear energy sector would ensure a stable, long-term supply of electricity, particularly as energy demands grow with economic development. It would also allow Kazakhstan to export excess electricity to neighboring countries, further solidifying its role as a key energy player in the region.

“By developing nuclear energy, Kazakhstan can diversify its energy mix, reducing dependence on fossil fuels and enhancing energy security. Moreover, it would enhance Kazakhstan’s position in the global nuclear energy market, transitioning from a raw material supplier to a country with advanced nuclear technology capabilities,” the NANO Nuclear Energy expert stressed.

Presently, nearly 80% of electricity in Kazakhstan is generated by burning coal, approximately 15% is produced by hydropower, and the remainder comes from renewable energy sources. Although Astana is seeking to develop its green energy sector, hoping to eventually begin exporting “green electricity” to Europe, it is unlikely it can achieve such an ambitious goal without nuclear power.

As the US author Michael Shellenberger highlighted in his 2016 New York Times article, the only countries that have successfully moved from fossil fuels to low-carbon power have done so with the help of nuclear energy. It is, therefore, no surprise that the European Union, particularly France, which is very interested in Kazakh energy, is aiming to develop a nuclear partnership with Astana.

But will French, or other European corporations, be involved in the construction of the first Kazakh nuclear power plant?

“Companies like EDF (Électricité de France) or Framatome have significant experience and a reputation for high safety and environmental standards. However, European involvement would likely come with strict regulatory requirements and potentially higher costs, which might be less attractive to Kazakhstan compared to the more financially flexible and geopolitically aligned options presented by Russia or China,” Walker concluded.

It is no secret that Russian companies officially control about 25% of Kazakhstan’s uranium, and that Rosatom plans to build a small nuclear plant in neighboring Uzbekistan. Also, the fact that Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Kazakh counterpart Kassym-Jomart Tokayev discussed energy cooperation amid Astana’s plans to hold a referendum on the construction of a nuclear power plant, clearly indicates that Moscow has significant nuclear ambitions in Kazakhstan.

The Kremlin is undoubtedly aiming to preserve Central Asia in its energy sphere for influence, fully aware that its potential involvement in the construction of a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan would make Astana dependent on Rosatom’s maintenance. Consequently, the former Soviet republic would, at least in the field of energy, remain in Moscow’s geopolitical orbit.