For much of its recent history, Kazakhstan’s image has been shaped by the discourse of natural resource extraction — oil, gas, metals, the infrastructure to transport them, and the political influence they provide. But, a quiet transformation of its public and private spaces is underway, one not measured in barrels, commodity prices, or contracts, but by lighting or lights, which means ambience, illumination, aesthetics, and the atmosphere of lived space. Lighting, of all things, is central to human existence and part of its development story.

It may seem peripheral, but in architecture, lighting is never neutral. It guides, reveals, softens, and dramatizes space. It also mirrors taste, cultural aspirations, and society’s choices.

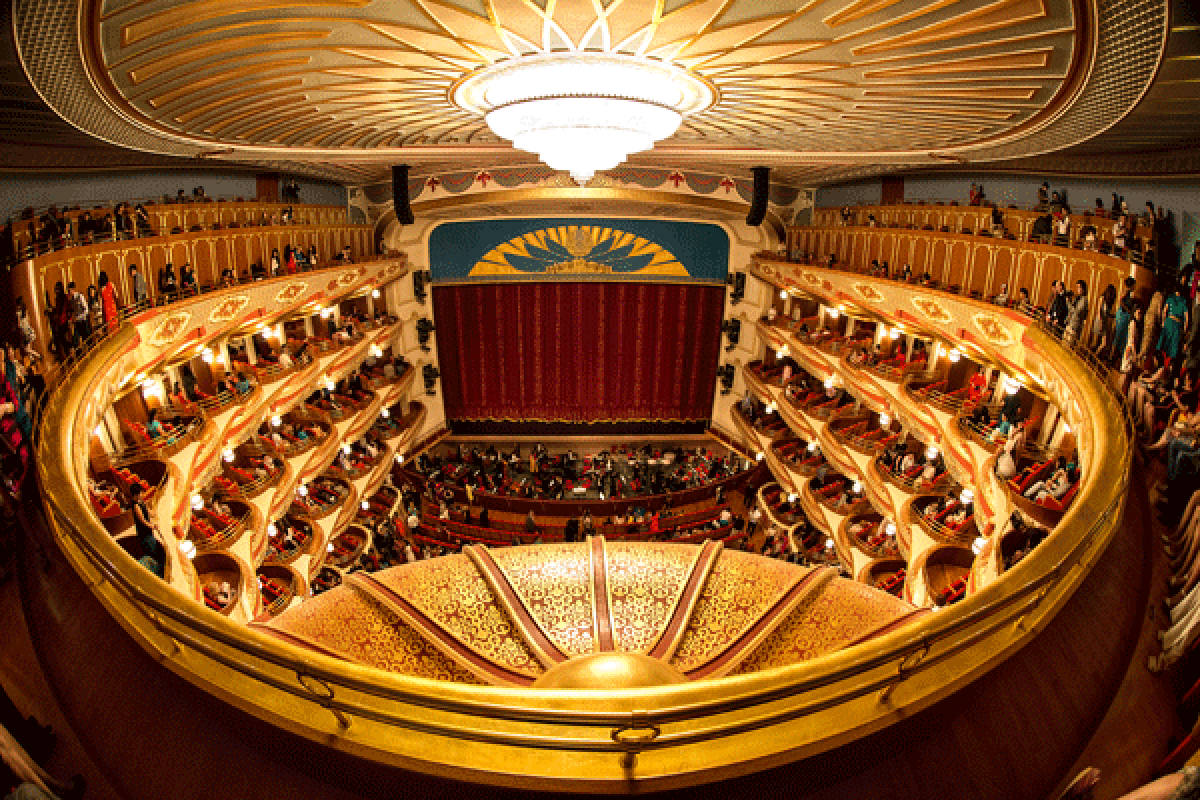

Astana Opera; image: Dilyara Abdirakhmanova

Light is the Language of Architecture and Space

Some of Kazakhstan’s most emblematic public buildings already utilize the optimal use of lighting. The Astana Opera, for example, with its marble staircases and opulent chandeliers, is illuminated to bring out its grandeur and high culture. Its stage is masterfully lit so that musicians are inspired to give their best performances. Likewise, the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, a crystalline pyramid designed by Foster + Partners, plays with transparency and glow, its stained-glass summit flickering between monument and mirage, giving voice to the need for peace in our time.

Then there’s the Khan Shatyr Entertainment Center — part shopping mall, part climate-controlled urban experiment — which glows at night through its tensile skin – representing a range of civic and family-friendly amenities offering a comfortable and eye-pleasing microclimate for all. And then there’s the Hazrat Sultan Mosque, designed and lit for reverence and reflection. Daylight barrels through high arches; at dusk, soft interior light catches the tracery of Quranic calligraphy, domes, and minarets. The lighting is generous but subtle, quiet, and precise.

In each of these cases, light isn’t an afterthought. It reaches out to the subconscious and makes daily human activity more pleasant.

The Palace of Peace and Reconciliation; image: Foster + Partners

A Gap in Everyday Life

Until recently, there has been little discussion in Central Asia about the link between lighting and its impact on the human person. Walking through many apartment buildings, offices, restaurants, and public lobbies, the atmosphere is flat, cold, and covered in uninspiring glare, often overpowering and at times blinding. These spaces may function, but they don’t resonate and are often uninviting. This state of affairs – the depressing nature of fluorescent grids – in the world of lighting is beginning to change, slowly, and unevenly.

This shift towards ‘more welcoming’ lighting isn’t being driven by architects alone, or even by design schools. Demand comes from developers, hoteliers, homeowners, and restaurateurs who want to serve their clients better in an increasingly competitive environment. In this more mobile and inquisitive world, people want lighting that feels and works better for clients, employees, and oneself.

A Market Beginning to Notice

Enter enterprises like iSquare, a recently launched lighting design firm in Almaty. Its operating premise is modest: to help clients think about light earlier and do it with access to European brands and technical guidance that recognizes clients’ physiological and emotional needs. At its launch this summer, iSquare made no sweeping declarations, just a quiet suggestion that Kazakhstan’s conversation about design and the use of space is maturing, i.e., that thoughtful lighting is critical for creating friendly work or living spaces.

Speaking with The Times of Central Asia, co-founder Manish Wahie says that “The demand for refined European design, for brands with heritage and innovation, is growing. But, just as iSquare exists because the market is ready for it – a sign of confidence in the future – many new companies are also breaking into the market.”

Wahie puts it plainly: “The desire for better lighting has always been there; what’s changing is the availability of tools and know-how to meet it. The firm doesn’t represent a revolution, but a recalibration — one of several small signals that people are beginning to value space not only for what it contains, but for how it makes them feel.”

The Hazrat Sultan Mosque; image: U.S. State Department

Light as Mood, Light as Class

Like scent and sound, light operates somewhere between utility, the laws of physics, and emotion. In the post-Soviet context, emotional design has sometimes carried the whiff of indulgence and discordant space. That’s no longer the case. Whereas during the Soviet period, function was often prioritized at the expense of harmony and comfort, today beauty and coherence – the idea of giving birth to objects in order to change the way of living – take precedence over functionality.

To be sure, lighting has increasingly become a marker of social intention and progress. It can signal wealth, but more often it suggests attention, care, and purposeful aspirations. Whether it’s a warm pendant over a dining table or the delicate uplight on a gallery wall, the message is: “someone thought about this.”

This attitude towards one’s work and living space has implications beyond interiors. Kazakhstan’s growing interest in design — and lighting, specifically — isn’t just about taste. It’s about the economy. Countries that invest in their milieu – work-space – are more likely to attract creative talent, tourism, and innovation. The type of lighting that fills a lobby, hotel, or office makes life and living all the more pleasant.

Toward an Independent Atmosphere

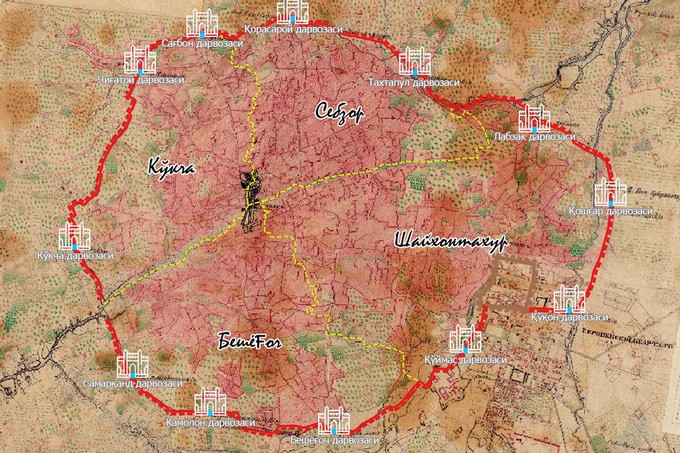

It is not only in Astana and Almaty, but across Central Asia, cities are in motion. There are cranes, master plans, bulldozers, and towers going up in Tashkent, Bishkek, and elsewhere. What happens in new buildings, however — how they feel, what they express — is discussed as a strategic proposition.

Design matters. So does light. It’s not just the glow on a wall or the color of a ceiling wash. It’s creativity in motion, a conversation between building and person, between idea and perception.

The cities of Central Asia do not need to become like Milan, Tokyo, or Copenhagen. They can come up with their own vocabulary of materials, shadows, colors, and brightness. What’s important is that people here are beginning to notice the link between lighting, productivity, and quality of life — and to care strategically about their working and living environments.

That might be the clearest sign that things in the region are changing – not in what’s being built, but in how space is seen, how lighting motivates, and how it is personally experienced.