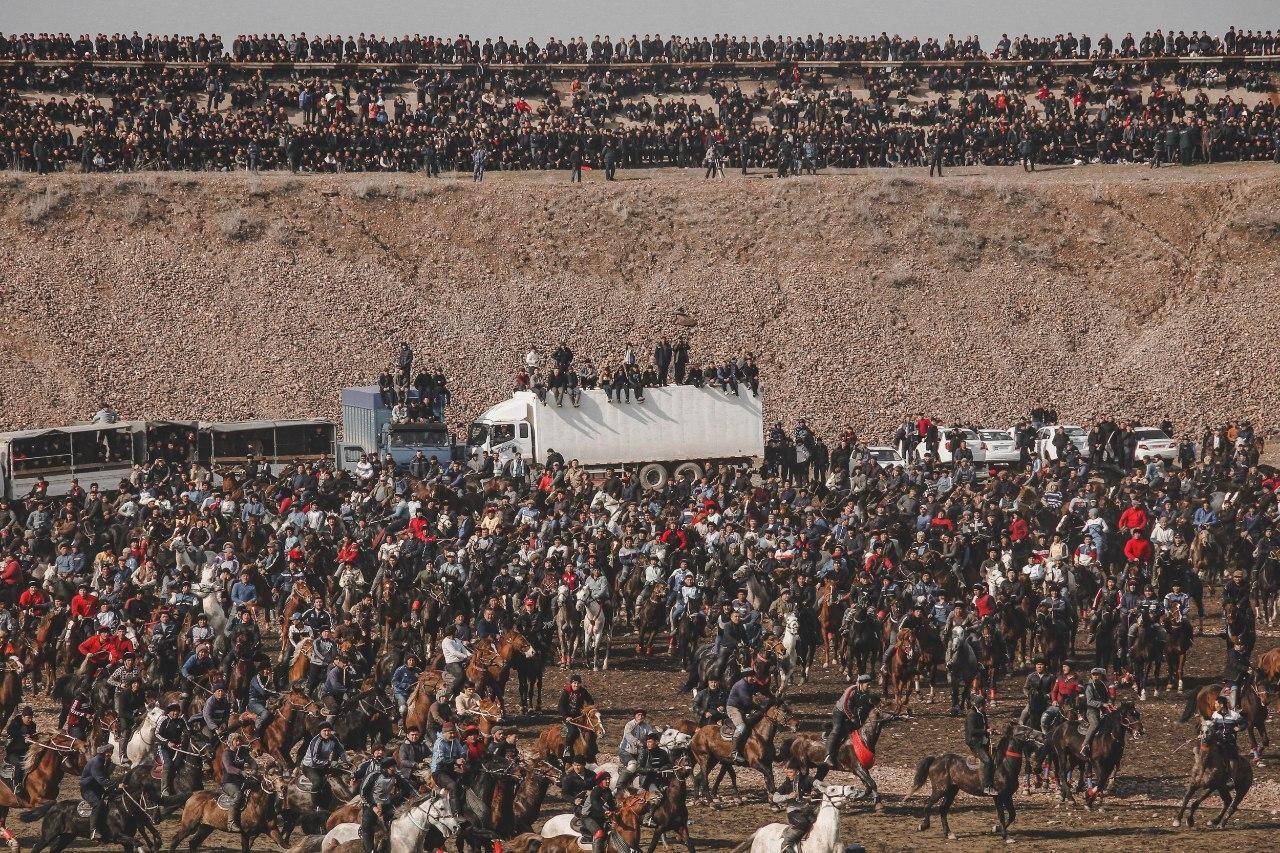

The assignment for the Uzbek deaf photographers’ workshop: cover a game of kupkari, in which horse-riders jostle for a goat carcass and hustle it to a goal amid shouting, shoving and swirling dust.

It didn’t go well for student Murod Yusupov, who arrived late at the event in Piskent, in the Tashkent region, and then struggled to orient himself in the boisterous crowds watching the maelstrom on the field.

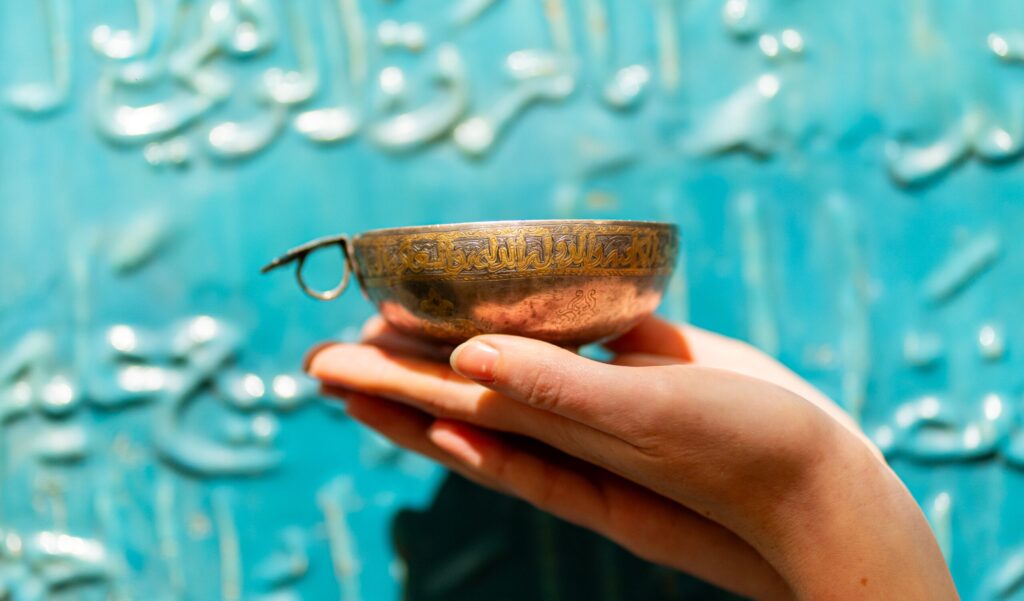

Crowds watch a game of kupkari, a traditional sport in Uzbekistan (Photo: Khuvaido Fatihojayeva)

“Unfortunately, I was a little late, and I had to stay among the fans. Communication with the teacher and participants was almost non-existent. But it was a big problem to take pictures there, there were too many people who came to watch the kupkari, I didn’t have enough experience to find a convenient place and opportunity to take pictures,” Yusupov said through a sign language interpreter in an interview with The Times of Central Asia.

He learned from the experience, though. With the help of workshop director Husniddin Ato, 21-year-old Yusupov got accredited for the Asian Weightlifting Championships in Tashkent in February and delivered strong images. Best of all, he enjoyed the assignment.

Uzbek athlete performs during the Asian Weightlifting Championships in Tashkent in February. (Photo: Murod Yusupov)

—

One recent evening, at the Bon Cafe in Tashkent, Ato, Yusupov and several other participants in the “Deaf Photographers” workshop talked about their experiences and hopes to a correspondent from The Times of Central Asia. Ma’mur Akhlidinov, a sign language teacher at the University of Uzbek Language and Literature who is also deaf, helped to interpret. Cups of sea buckthorn tea were served during a conversation lasting two and a half hours. The deaf photographers were upbeat, often smiling, communicating with each other through hand gestures and showing photos on their phones to each other.

—

A decade ago, Ato, a professional photographer, wanted to report on deaf people. Then he decided to let deaf people show in pictures how they feel about the world. While in quarantine during the pandemic, he consulted Akhlidinov, a member of the Deaf Society of Uzbekistan.

For many years, Akhlidinov worked as a designer in the editorial office of Ma’rifat, an Uzbek publication, and as the editor-in-chief of the MediaPlus project. Akhlidinov was surprised by the fact that there wasn’t a single internet resource about deaf people and their rights in Uzbekistan. In 2017, he launched a blog for deaf people, their parents and educators.

Akhlidinov supported Ato’s proposal for an initial three-month course. and announced the project on the Deaf Society blog, which has more than 1,000 subscribers. An age requirement (18-25) was set for the participants. Nine people signed up.

In the fall of 2021, the teaching started. It was slow going at first because of scheduling conflicts and other obstacles.

“Later, their interest and enthusiasm wasn’t always there, they didn’t complete their assignments on time, and I had to explain some things over and over again. Due to such problems, the three-month course lasted a long time with interruptions,” said Ato, who has learned basic sign language.

In 2022, Ato successfully applied for funds from the Washington-based Meridian International Center, a non-profit group that implements an awards program in partnership with the U.S. State Department. “Projects by individual eligible alumni are granted funding of up to $5,000 to facilitate positive changes within their communities,” Meridian said.

Thanks to the support, an exhibition of photos of the project participants was organized in the Tashkent House of Photography in March 2023. “We were able to pay the translator only because of this grant, and before that, both I and the translator worked as volunteers,” Ato said.

These days, former workshop participants often meet and talk with their mentors. Ato now wants to organize another workshop – not only in Tashkent, but also at a regional level. The big challenge is funding.

—

Deaf photographer Gulnoza Shermamatova, 25, said her hearing problems started when she got a bad cold at the age of seven. Various medical treatments, including what she describes as a doctor’s overreliance on prescribing antibiotics, failed to stem the deterioration. Shermamatova lost her hearing completely when she was 12-years-old.

Ato is coaching Shermamatova and other deaf photographers without charge, even though there is no formal workshop underway.

Shermamatova, who is currently studying for a master’s degree in art, wants to teach photography and is learning how to use photo editing programs.

“I like taking pictures of landscapes. Green is one of the most beautiful colors for me,” she said. “I have depicted many scenes of my hometown, the village of Oq Oltin in my paintings. I also like to take pictures of people’s emotions. I try to get more random pictures. If I feel the kindness of people, I will take pictures of them. In most cases, I have to ask their permission. It’s a pleasure to photograph people looking at the horizon, the sky, and I’ve captured this a few times.”

A rural scene in Oq Oltin village, Navoi Region, Uzbekistan. Oq Oltin is the photographer’s hometown (Photo: Gulnoza Shermamatova)

—

After starting the project, Ato looked for deaf photographers on the internet and watched YouTube videos of deaf photographers in other countries. He wanted to use the videos in his teaching, but found out that sign language is not the same everywhere. Uzbek deaf people, for example, use Russian sign language.

“Recently, we invited the British deaf photographer Stephen Iliffe as part of the project, he gave a two-day master class to the participants,” Ato said. “For the participants, we engaged two experts who understand English and translated into local sign language. My students were well motivated.”

British deaf photographer Stephen Iliffe, in striped shirt, works in a studio with Uzbek deaf photographers. (Photo: Husniddin Ato)

During his visit to Uzbekistan in May, Iliffe showed how he creates a frame in Photoshop by superimposing two or three pictures of sign language speakers, and joined the students on photography assignments.

British deaf photographer Stephen Iliffe, lying on ground, shares his skills with Uzbek students. (Photo: Husniddin Ato)

Employers of deaf photographers must find ways to communicate effectively, often via text message, according to Ato. He said his students have the skills to work in photo studios or media and that “photos taken by the deaf are almost indistinguishable from those of ordinary photographers.”

Akhlidinov, the sign language interpreter, said there were damaging stereotypes that “the deaf cannot work” or are only good for manual work such as in factories and construction sites.

It hasn’t worked out for all the deaf photographers. Ato said one talented student had to sell his own camera because he needed the cash and is now working in a parking lot.

—

Another talent is Farangiz Kamalova, a 21-year-old student of computer graphics and artistic photography at the National Institute of Painting and Design in Tashkent. She enjoys nature, people and portrait photography and wants to participate in international photography competitions but needs help navigating the application process. Akhlidinov said that’s because some hearing-impaired and deaf people have more limited vocabularies.

The quality of education and other kinds of support can affect the development of vocabularies for deaf people.

Khuvaido Fatihojayeva, 21, was one of the first workshop participants and knew virtually nothing about photography.

“During the project, H. Ato took us to Samarkand, Bukhara, Gulistan and organized master classes there,” she said. “Since I was born in Tashkent, I didn’t know the situation in the rural areas. During the trip to the regions organized by the teacher, it was very interesting to get to know village life, its people, and capture them in the frame… In the future, I intend to go to every region of Uzbekistan and photograph interesting topics such as people, lifestyle. I also have a big dream to travel the world and take in the world’s architecture and people.”

Fatihojayeva wants to open a photo studio and is interested in portrait photography as well as photographing buildings and architectural features.

Birds flutter around a man in the ancient city of Bukhara (Photo: Khuvaido Fatihojayeva)

—

Yusupov, who had a hard time at the kupkari event, prepares photo reports for media outlet Gazeta. One report was prepared on a horse parade held on International Children’s Day in Tashkent. He has also reported for Suvmap, a USAID-backed project aiming to promote sustainable use of water resources, working on various assignments related to water and irrigation.

Yusupov, a history undergraduate at the National University of Uzbekistan in Tashkent, loves photographing nature and sports.

“Last year, I invited my friends and teacher to my hometown, Bayovut district, Sirdarya region,” he said. “We took pictures of people’s lifestyles, landscapes, and the birds there.”