TASHKENT (TCA) — Although there has been a marked change in the government’s attitude toward believers, being devout Muslims still remains dangerous in Uzbekistan. We are republishing this article on the issue, originally published by Eurasianet:

The opening hearing of Guzal Tokhtakhadjayeva’s criminal trial last month began late because of the hubbub that day at Tashkent city court.

On April 16, an unusually large crowd of rights activists, foreign reporters and well-wishers had gathered outside the court in Uzbekistan’s capital to hear another day of testimony in the state’s case against a well-known journalist accused of sedition. Few gave Guzal much heed.

Both trials, however, may prove to have had equally consequential implications for the nation’s future.

The journalist, Bobomurod Abdullayev, ultimately walked out of court on a suspended sentence in what some took as a signal of the government’s willingness to ease its intransigence toward the press. The other case may provide clarity about where the state stands in its evolving relationship with fringe religious communities.

Guzal, a 31-year-old from one of Tashkent’s old quarters, was in the dock with her husband Muhammad Rashidov on suspicion of distributing propaganda materials of a proscribed Islamist group and seeking to undermine the constitution. Another two relatives, a mother and son, are also on trial.

In court, the prosecutor read out the accusation against Guzal in a monotone drone.

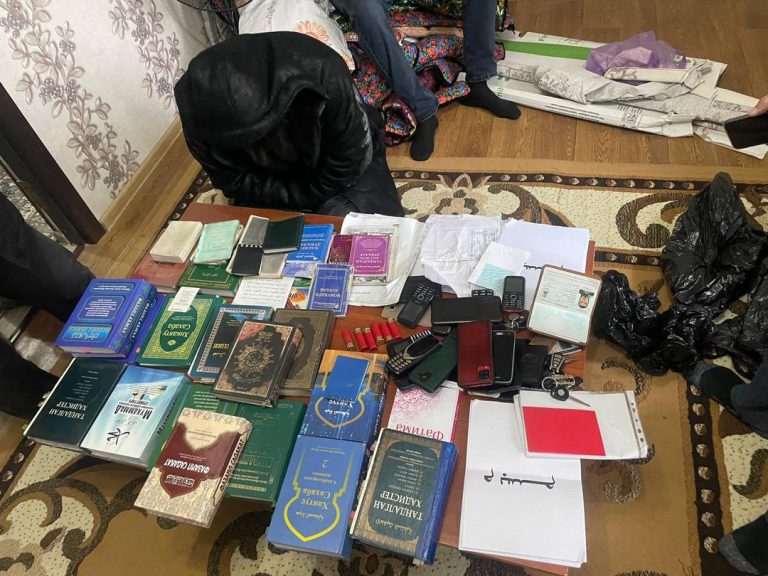

“She engaged in the distribution of literature and leaflets and was also gathering funds for Hizb ut-Tahrir. She was observed by police operatives handing out 14 leaflets outside a mosque in Tashkent,” he said.

Guzal rejects the specific charges, although her association with the group appears less in doubt. Almost all her immediate family have at some stage served time – or are still serving time – for their dealings with Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Hizb ut-Tahrir was founded by a Lebanese Islamic scholar in the early 1950s and quickly took root across parts of the Middle East. Its very name, which is Arabic for Party of Liberation, strongly suggests an ethos no less political than it is religious. The party’s ideology combines a deep aversion for secular political order with often unabashedly intolerant views for anything perceived as un-Islamic. The group is banned in most of the former Soviet Union, though it operates openly in the West.

Though in the immediate aftermath of independence Uzbekistan’s authorities pressured most religious thought outside the state-sanctioned orthodoxy, Hizb ut-Tahrir and similar-minded groups flourished in the 1990s.

It was only around 1998 that the onslaught became truly ferocious.

The history of arrests for links to Hizb ut-Tahrir in Guzal’s family began in November 1999, when her father, Aziz Tokhtakhadjayev, was picked up by law enforcement officials on suspicion of being a member.

Aziz was an academic and taught economics the Tashkent State University of Economics. He obtained his doctorate degree in Soviet times at what was then called the Plekhanov Moscow Institute of the National Economy.

Initially, Aziz was sentenced to 13 years in jail. That penalty was extended by another 16 years in 2013.

“They have extended his sentence several times on various concocted grounds. The last time it was charges […] of dangerous recidivism. Now this 70-year-old, this severely ill man, is being kept in a high-security jail. He is not eligible for amnesty,” said Dildora Agzamkhadjayeva, another of his daughters.

Yet another sister, Dilnoza, 36, ended a three-year jail sentence in 2010. She spent her term in barracks holding 100 women.

“In the [prison] colony I worked in a sewing factory where they made jackets, clothes for builders, and also clothespins. The worst thing was that a representative of the National Security Service would come to visit twice a month,” Dilnoza told Eurasianet.

Rights activist Azgam Turgunov, who visited Dilnoza in prison, relayed accounts of how she had been dragged by the hair and had her head slammed against the wall while serving her sentence. Dilnoza refused to elaborate on the details of these alleged incidents, turning away when asked.

At the opening hearing of her trial, Guzal, a slim and pale woman with slight features, appeared undaunted and even defiant. Her husband, meanwhile, seemed bowed and defeated.

Speaking from a defendant’s cage guarded by five policemen with guns and batons, she told the court her life story: While at middle school, she dreamt she might be able to enter medical school. But the family was too poor and her mother fell ill, so she had to ditch her studies. When she turned 18, her parents gave her away in marriage, as is customary among traditional families in Uzbekistan. She and her husband now have three children.

Although the Tokhtakhadjayev family barely disguises its sympathies for Hizb ut-Tahrir, Guzal rejects the exact charges being leveled at her. She told the court that she was subjected to psychological pressure and intimidation while under questioning.

“Investigators said that if I did not confess to the charges, that they would strip me and send me to a male holding cell. That my children would be put in an orphanage. And that I would in any case be sent to Jashlyk,” she said, referring to a notoriously harsh penitentiary in the remote deserts of western Uzbekistan.

Surat Ikramov, a Tashkent-based rights activist following the case, said that he believes accusations on religious grounds are typically falsified and confessions extorted through maltreatment. All the accused are usually guilty of, he said, is being devout Muslims and getting together to express their devotion.

“They are all relatives and would get together to pray,” Ikramov said, referring to the Tokhtakhadjayevs. “They are all believers and recite the namaz [daily prayers].”

The specific charges of distributing leaflets is crucial in cases like these, otherwise prosecutors find themselves having to advance the argument that people are members of Hizb ut-Tahrir merely on the basis of the state’s say-so.

“There is no religious organization. If many believers get together in one place, then law enforcement immediately assumes that they are trying to create a religious group. They are violating people’s right to religious freedom,” said Ikramov.

Still, Hizb ut-Tahrir does exist, although the scale of its support and, perhaps more importantly, the extent of the threat it poses is the subject of much conjecture.

Viktor Mikhailov, director of the Tashkent-based Center for Regional Threats, told Eurasianet that the first time Hizb ut-Tahrir literature began cropping up in the Soviet Union was in the 1970s and that the movement began to make more of a headway in the 1980s.

Hizb ut-Tahrir cells tend, according to those who have studied its evolution in Central Asia, to emerge from within family groups or among close-knit acquaintances. It is notable for being particularly well represented among women.

“By some estimates, the party’s membership is around 15 percent female. They are the only [political party in Uzbekistan] with such a strong female wing,” Mikhailov said.

Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who came to power after his predecessor died in September 2016, there has been a marked change in attitude toward believers, including many once considered anathema to acceptable society. In 2017, around 16,000 out of 17,000 names were removed from a list of suspected extremists singled out for regular monitoring.

It may still be too early to understand what the significance of that gesture was, however. Some religious figures have begun to spread their wings with inflammatory outbursts. But such language has been directed on the whole against groups also disliked by the authorities.

One exemplary episode occurred in November, when well-known imam Shermurad Togai issued a fire-and-brimstone proposal that the death penalty be adopted for members of Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Islamic State group. Before Mirziyoyev’s time, there was hardly an imam who would have dared offer such exotic policy recommendations, but such invective nowadays elicits little more than gentle chiding, if anything. When disapproval comes, it is from social media rather than the secret police.

The outcome of Guzal’s trial will clear away some of the ambiguity currently prevailing in religious life, by either indicating a softening or reaffirmation of erstwhile hardline positions. A guilty verdict is beyond certain, since Uzbekistan’s courts only formally acknowledge any other possibility, but the severity of the penalty will be telling.

“I really hope the court is humane toward Guzal Tokhtakhadjayeva and the other defendants,” Ikramov told Eurasianet. “After all, Bobomurod [Abdullayev] was also accused under [the criminal article for undermining the constitutional order], just the same as Guzal.”