LONDON (TCA) — Many sideliners have remained in the dark over what China had in mind on launching its “One Belt, One Road” scheme on the Eurasian mega-continent back in 2013. Especially China’s entry into agro-sectors in neighbouring Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan made people in those countries restless. It is now becoming clear that as developments in China’s food-related commitments are concerned, the plan is part of a much broader master-scheme.

Following “popular resistance” against the purchase or even leasing of territory by foreign corporate entities or individuals, the governments of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have been frantically looking for formulas to attract the necessary funds to consolidate and improve their underperforming agro-sectors. This was done trying to avoid provocations attributed to local businessmen earning fortunes on imports and ready to do anything to keep domestic farmlands lagging behind.

While establishing a network of corporate clout in various agro-sectors and subsectors outside China as a warning sign or a logical reaction to such signs of “sinophobia” in neighbouring regions, Beijing has launched a massive-scale master plan to free itself from any dependence on imports.

‘Overseas businesses’

Russia Today reported in the third week of September referring to China’s state news agency Xinhua, “Over the next four years the Chinese government will invest 3 trillion yuan ($450 billion) into developing the country’s agriculture …. The Agricultural Development Bank, one of China’s main policy lenders, will provide the finance including setting interest rates and offering financial products.”

The plan might well worry beneficiaries of Chinese investments in the food sectors of its near-abroad which are dwarfed by those in China’s domestic agro-sector. As to date, China has invested a total of 7.18 billion expressed in US dollar in overseas agricultural projects, making up 10.9 percent of total outbound investment, according to a recent report posted by Xinhua. And more is on the way: recently, China’s state-owned ChemChina chemical corporation raised its bid to takeover Swiss agrochemicals and seed supplier Syngenta to $43 billion, Russia Today reported recently.

Beef, lamb and horsemeat

In particular Kazakhstan, where agriculture produces surplus outputs but remains economically underperforming, has seen Chinese cash flows coming in, in a shift away from oil and gas and directed at more sustainable sectors.

As reported by The Financial Times in May this year citing information coming from Kazakh officials, “Investments under consideration in Kazakhstan’s agriculture sector include $1.2bn by Zhongfu Investment Group into oilseed processing, $200m into beef, lamb and horsemeat production by Rifa Investment; and $80m into the production of tomatoes and tomato paste by Cofco, China’s state agriculture conglomerate.”

China needs the former Soviet republics’ overcapacity to secure its domestic supplies – for the moment, that is. China is expected to produce 128 million tonne of wheat in the current marketing year, with carryover stock remaining in the order of 100 million tonne. This means that it has to import an extra 30-40 million tonne in order not to start “eating” reserves. Besides, the People’s Republic spends the equivalent of $100 billion each year on farm subsidies. This means that markets for Kazakhstan and Russia are secured for the moment – but not that this will remain so forever.

The main challenge: cereals

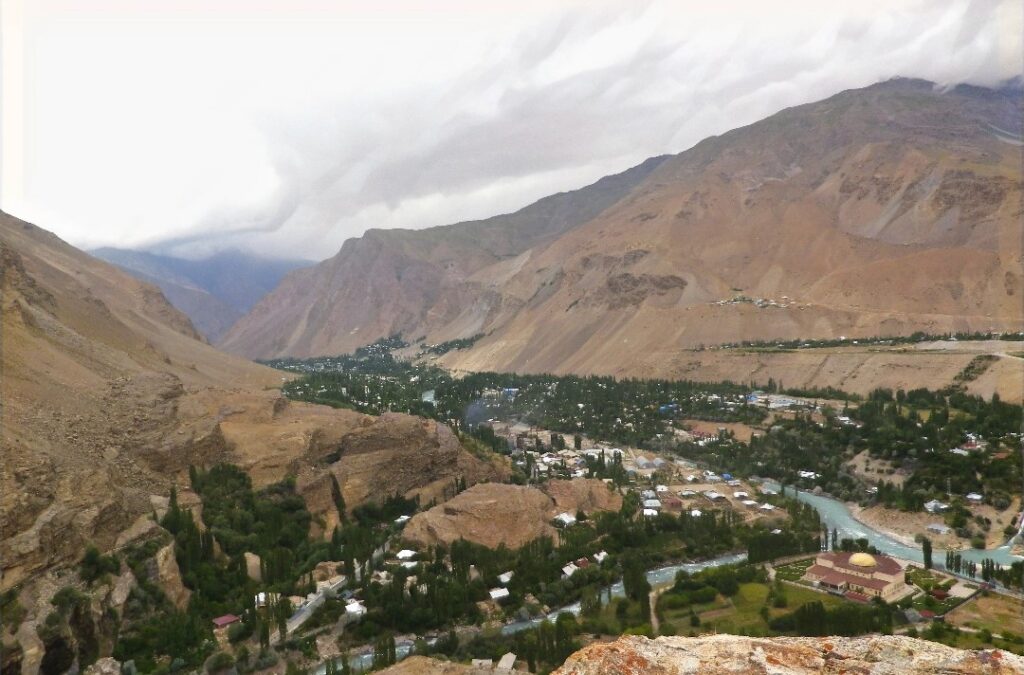

In Kyrgyzstan, the agro-sector of which engages almost two-thirds of the population but represents hardly more than one-sixth of its economic clout, the problem is even more acute and so is the need for a sound financial base to generate a decisive sector development breakthrough.

In contrast to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan is a net importer of wheat but very much like its neighbour to the north heavily underuses its farming production capacity. The so-called bilateral strategic partnership treaty with China inked by Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Kyrgyz counterpart Almazbek Atambaev during Xi’s visit to the Central Asian country in 2013 is already bearing fruit. According to a report posted on May 30 this year by Xinhua, this year for the first time Kyrgyz farmers are selling substantial amounts of vegetables, leather and wool to Chinese customers while importing mainly chicken, pork and eggs from them.

In cotton farming, which has already benefitted from Chinese assistance in the form of research, supplies of state-of-the-art seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides since 2003, while compensating in the form of discounts on exports of cotton half-fabricates and end products (clothing), cooperation is now taking shape on a much larger scale.

The main challenge for investors and farmers alike in Kyrgyzstan lies in cereals, though. Prior to the spring crop sowing campaign that took place in April this year, the FAO predicted a setback in output of grain, particularly wheat and maize, to 1.4 million tonne from 1.7 million in 2015. In the last summer-to-summer market year, Kyrgyzstan had to import more than half a million tonne of wheat to secure bread on the shelf for the population. It means that China’s strategies in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan may look different, but their overall goal is the same: ensure continuity in supplies for China’s fast-growing consumer markets.