Central Asia’s Crypto Gamble: Growth Amid Uncertainty

Central Asian countries are approaching the cryptocurrency and crypto-mining industry at varying speeds. While some are just beginning to explore the sector, others have already taken significant, albeit sometimes contradictory, steps.

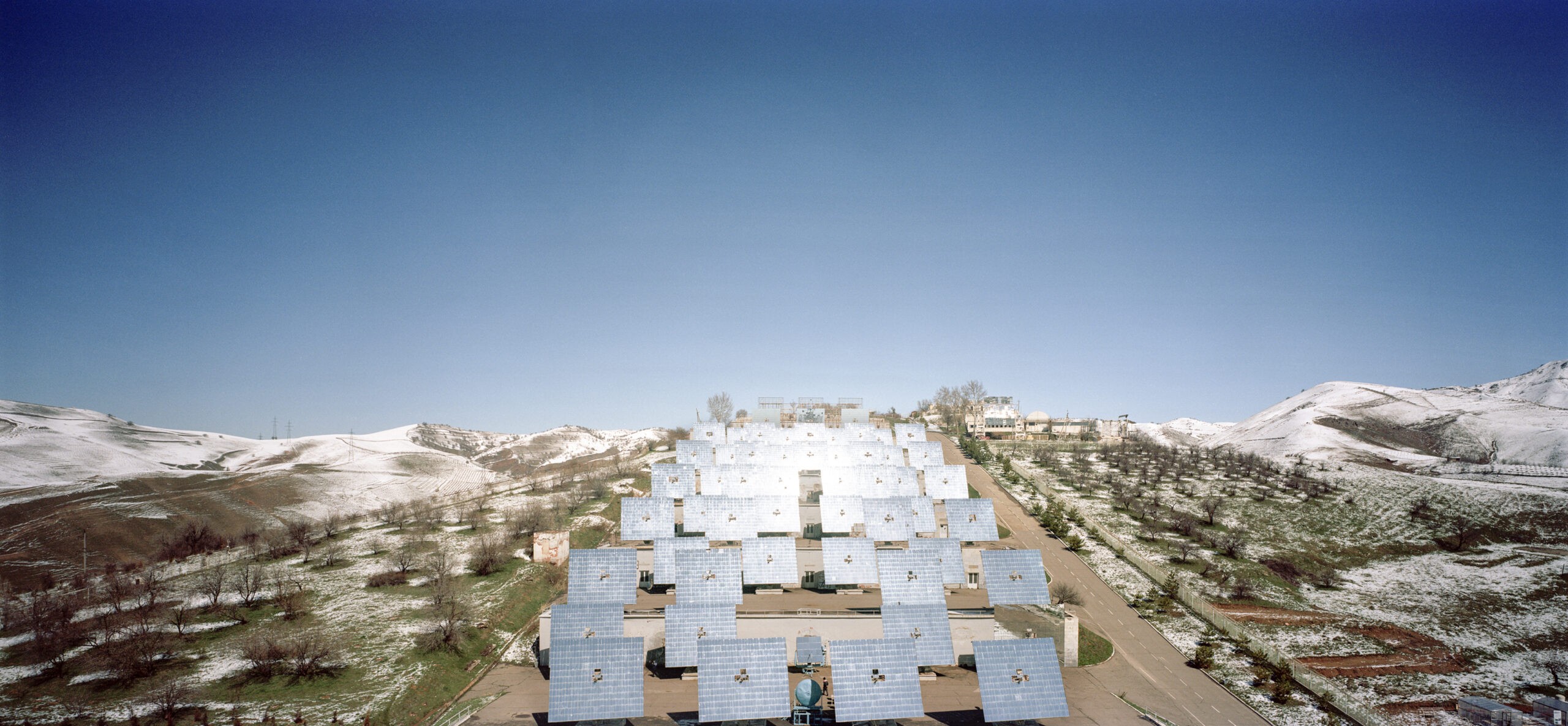

Kazakhstan: From Mining Powerhouse to Regulatory Caution

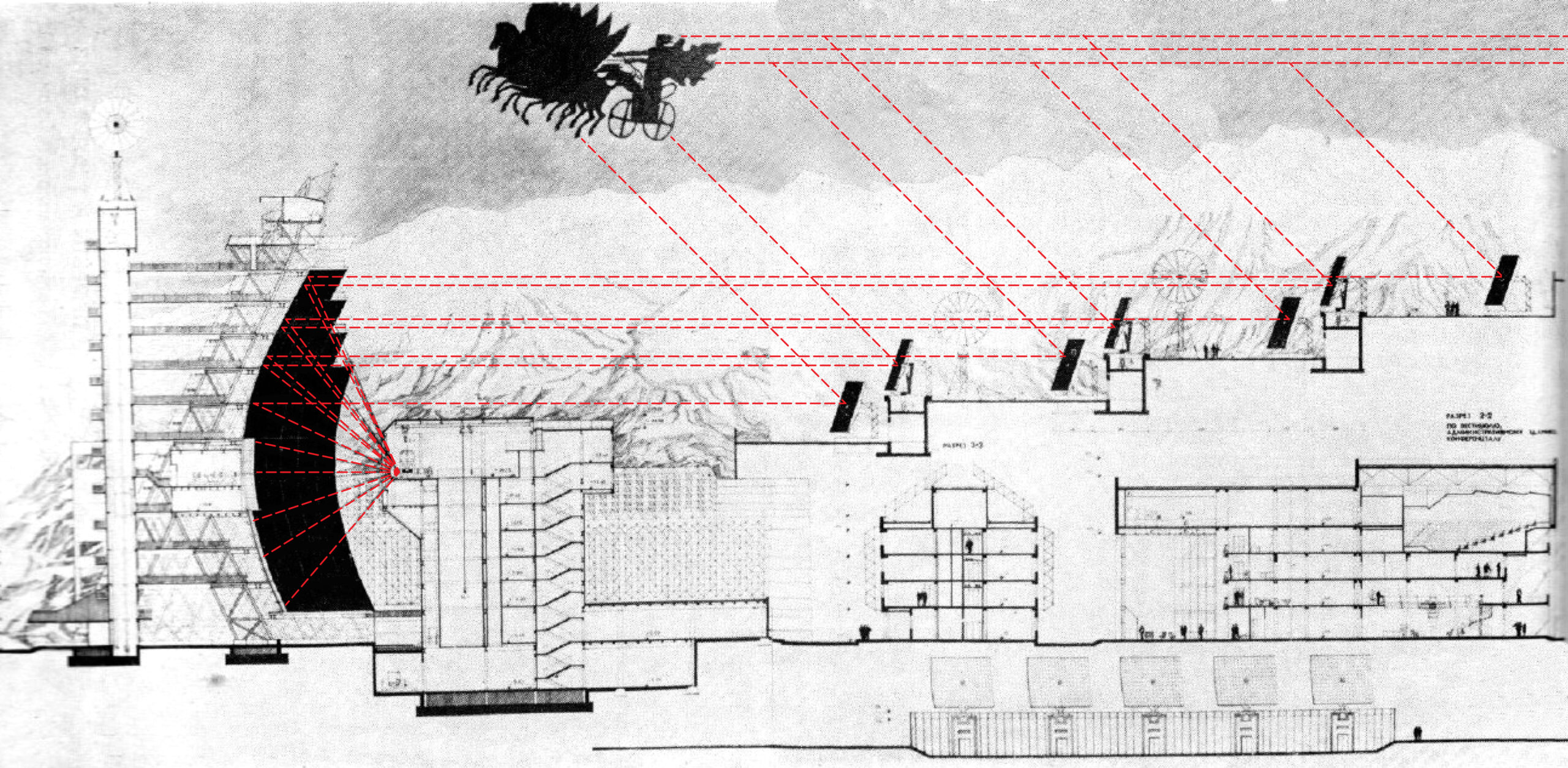

Kazakhstan once emerged as a global leader in bitcoin mining. Between mid-2021 and early 2022, the country ranked third in the world in terms of bitcoin mining capacity, accounting for 13.22% of global computing power, trailing only the United States and China. This boom was fueled by low electricity costs, favorable tax conditions, and an influx of miners fleeing stricter regulations in China.

However, the rapid growth strained Kazakhstan’s energy infrastructure. The Ministry of Energy reported that while annual electricity consumption had previously grown by an average of 2%, in 2021 it surged by 6.1% and up to 12% in the densely populated southern energy zone. Digital mining was cited as the primary cause.

By early 2025, Kazakhstan’s share of global mining capacity had dropped to just 1.4%, placing it outside the top five globally. Although around 60 companies are currently active in the sector, some operations have stalled. Tax legislation has tightened since 2022, with miners required to pay 1-2 tenge per kilowatt-hour depending on the energy source. Illegal mining and unlicensed exchanges remain a challenge; in 2024 alone, 12 criminal cases were launched against underground platforms.

Despite these setbacks, experts see potential for a more sustainable and regulated industry. The Astana International Financial Center (AIFC) has become the hub for cryptocurrency operations. A 2023 law on digital assets and updated rules from the Astana Financial Services Authority (AFSA) in 2024 have laid a more comprehensive legal foundation, including provisions on cybersecurity and anti-money laundering.

Over 10 licensed cryptocurrency exchanges now operate in Kazakhstan, including global names like Binance, Bybit, and Bitfinex Securities. New initiatives such as the digital tenge and the Cryptocard aim to further integrate blockchain into daily financial transactions.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev reaffirmed the government’s commitment to digital transformation in March 2025:

“The development of the digital asset industry and blockchain technology plays a major role. Urgent measures must be taken to liberalize regulation, ensure the legal circulation of digital assets and crypto exchanges, and attract investment in digital mining,” he said.

Uzbekistan: State-Supported Growth

Uzbekistan has made blockchain and digital assets a policy priority. The National Agency for Perspective Projects (NAPP) is the main regulatory body. Between 2022 and 2024, the agency issued 14 licenses to cryptocurrency companies.

The UzNEX exchange, an internationally licensed platform, has played a key role in developing the crypto market in both Uzbekistan and the wider region. Its services include crypto asset trading, staking, and NFT transactions. In 2024, it expanded its list of supported cryptocurrencies (including Toncoin) and plans to launch a digital art platform. Total trading volume exceeded $1 billion in 2024.

Kyrgyzstan: Building a Legal Framework

Since 2022, Kyrgyzstan has actively developed its regulatory environment for digital assets. The key legislation is the Law on Virtual Assets, which outlines rules for the issuance, circulation, and mining of cryptocurrencies. It mandates licensing for exchanges and mining companies.

By 2024, Kyrgyzstan had registered 75 virtual asset exchange operators and seven full-fledged crypto exchanges. The volume of cryptocurrency transactions reached $4.2 billion.

Tajikistan: Cautious Progress

Tajikistan has yet to formalize regulations on cryptocurrency. While mining is not banned, it operates in a legal gray area. Miners are required to pay taxes, but the absence of comprehensive legislation remains a barrier.

However, in March 2024, Tajikistan established an Agency for Innovations and Digital Technologies, with a mandate to develop digital legislation.

Turkmenistan: Minimal Engagement

Turkmenistan currently has no legal framework governing cryptocurrency. The national banking system does not recognize digital assets as legal tender, which complicates access for users and potential investors.

Drive, Prudence, and Innovative Regulation

Central Asia’s engagement with the cryptocurrency and crypto-mining industries reflects a mix of ambition, caution, and regulatory experimentation. While Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan lead in infrastructure and adoption, Kyrgyzstan is quickly catching up with clear legal reforms. Tajikistan remains in early or exploratory phases. As global demand for digital assets continues to grow, Central Asia’s ability to balance innovation with regulation will determine its role in the next chapter of the crypto economy.