Scientists of Ancient Central Asia Still Relevant in the Modern World; The Idea of the Averaged Turkic Language

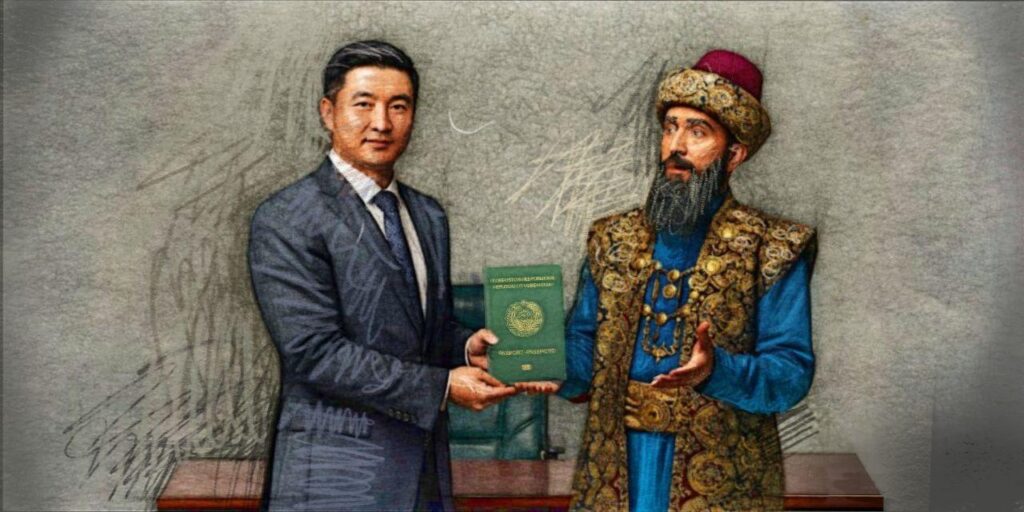

There is a debate on social media between Uzbek and Tajik communities about the medieval scholar Ibn Sina. The discussion revolves around the question of nationality — was Ibn Sina Tajik, Uzbek, or something else? Similar debates have emerged about other medieval scholars, including Al-Farabi.

Ibn Sina (commonly known in the West as Avicenna) and Al-Farabi were two of the most influential scholars of the Islamic Golden Age. Ibn Sina, known for his contributions to medicine, philosophy, and science, wrote The Canon of Medicine, a foundational text in medical education for centuries. First published in 1025, his work stood as the standard medical textbook in Europe from its translation into Latin in the twelfth century through to the 1650s. Al-Farabi, often called the Second Greatest Teacher after Aristotle, made significant contributions to philosophy, logic, and political theory, shaping intellectual thought in the Islamic world and beyond.

To explore this further, TCA spoke with two scholars — Fakhriddin Ibragimov, PhD, and Dr. Bakhtiyor Karimov — who have studied the lives and works of Ibn Sina and Al-Farabi extensively.

Fakhriddin Ibragimov; image courtesy of the subject.

Fakhriddin Ibragimov, a researcher at the Abu Rayhan Biruni Institute of Oriental Studies, has spent nearly 15 years studying Ibn Sina. According to Ibragimov, historical sources provide no direct evidence of Ibn Sina’s nationality.

“Ibn Sina (980 – 1037) was born in the village of Afshona, near Bukhara. Nowhere in his works or those written by his contemporaries is his nationality mentioned,” Ibragimov told TCA. “However, he is identified as a Muslim, like most people in Central Asia at the time. Also, many manuscript sources indicate that he was from Bukhara.” Ibragimov explains.

Ibragimov also highlights that Ibn Sina himself wrote about his upbringing, describing how he was raised in an intellectual environment where philosophical and religious discussions were common: “We had a lot of scientific discussions, debates, and gatherings at home. Issues of faith were also raised there. My father and brother adhered to the Ismaili faith [one of the religious movements in Islam that was widespread in the Near and Middle East in the 10th and 11th centuries], but I did not join them,” Ibn Sina wrote. However, he did not mention any ethnic identity in his works or in those written by his contemporaries.

Avicenna at the sickbed, miniature by Walenty z Pilzna, Kraków (ca 1479–1480); image: jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl

The claim over Ibn Sina’s legacy is widespread. While Uzbeks and Tajiks both regard him as one of their own, Iranians also consider him Persian due to the language of his writings. In 2018, a bust of Abu Ali Ibn Sina was installed in front of the campus of the Autonomous University of Madrid as a gift from the Iranian embassy. The inscription on the bust reads, “Persian physician and philosopher.” Even Jewish scholars have cited him as part of their intellectual heritage. However, Ibragimov argues that Ibn Sina should be seen as a global figure rather than being tied to any single nationality. “He was a product of the Bukhara civilization, but his influence belongs to the world,” he told TCA.

Bakhtiyor Karimov; image courtesy of the subject.

Similar discussions surround Al-Farabi, the renowned philosopher and scientist. Dr. Bakhtiyor Karimov, a leading researcher at the same institute, believes the evidence is clearer in Al-Farabi’s case.

Karimov argues that Al-Farabi’s nationality is not ambiguous. “His full name — Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Tarkhan ibn Uzlak Farabi at-Turki — indicates his Turkic origins. Historians of the time, such as Ibn Abu Usaybiya, explicitly referred to him as a Turkic.”

Karimov highlights that national identities were fluid in that era, and the names of distinct Turkic peoples emerged only much later. “Thousands of years ago, both Kazakhs and Uzbeks were named after a single Turkic people. National names appeared later; this was a slow process. The division into separate nations occurred about 2,500 years ago, but there are still about 20 Turkic peoples who speak a language closely related to each other. It is inappropriate to argue about whether a scientist is an Uzbek or a Kazakh – Farabi was a scholar of the Turkic world.

Pages from a 17th-century manuscript of al-Farabi’s commentary on Aristotle’s metaphysics; image: Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

“Not only Kazakhs and Uzbeks, but also representatives of Central Asia and all Turkic civilizations, and, of course, all of humanity, can be proud of Farabi. Studying Al-Farabi and his works would lead people to ask new questions about historical events. In my view, people would make a discovery through learning the scholars works, they would invent the O‘rtaturk tili [Averaged Turkic language], a language that would be understandable for all Turkic peoples,” notes Karimov. He believes that a shared linguistic system would help unify Turkic-speaking nations and strengthen cultural ties.

“There are around 300 million Turkic speakers worldwide. Many of these languages share a high degree of mutual intelligibility, with common words and similar grammatical structures. By standardizing these shared elements, we could create a language that would be understood by all Turkic peoples,” he explained.

Karimov first formulated this idea of the Averaged Turkic language with his colleague Shoahmad Mutalov 51 years ago, but due to political constraints at the time, they could not openly promote it. However, in 1992, after Uzbekistan gained independence, they published a book titled O‘rtaturk tili (The Averaged Turkic Language) to further elaborate on their concept.

In a recent speech, Karimov suggested that the Averaged Turkic Language could become a world language. “Six presidents of independent Turkic states (Turkish, Azerbaijani, Turkmen, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Kazakh) might write a letter to UN Secretary-General, Mr. António Guterres, requesting to include the Averaged Turkic language among world languages. Because about 150 million people speak Russian, and about 75 million speak French as native languages. About 300 million people speak various Turkic languages, but as I said above, speakers of these languages can understand each other 70-80% without an interpreter.”

TCA will explore this idea in greater depth in an upcoming article, examining its potential impact on cultural and linguistic unity among Turkic nations.

——-

Experts agree that the intellectual achievements of Ibn Sina, Al-Farabi, and other scholars of the 9th-12th centuries belong to all of humanity. Doctor of Historical Sciences Mirsodiq Is’hakov emphasizes the importance of unity rather than division: “The civilization of that time belongs to everyone. Our cultural past is shared. The scientists of that period are a collective heritage.

Language played a key role in the dissemination of knowledge. In particular, Arabic and Persian or Tajik were widely used in the Middle Ages, and Turkic languages also played a special role in cultural processes. “In those times, Persian was widely used for administrative and scholarly work. Even in Babur’s court in India, Persian remained the official language until 1858. But this does not mean everyone was Persian or Tajik,” Is’hakov clarified.

The debate over nationality may continue, but one thing remains clear: these scholars’ legacies transcend borders, enriching not just Central Asia but the entire world.