BISHKEK (TCA) — We are presenting to our readers Stratfor’s forecast for this year for the vast continent of Eurasia, with a particular focus on Russia and Central Asia:

2017 will be a year of opportunity for Russia. And if it capitalizes on those opportunities, some sanctions against it could be eased by year’s end.

Crowding Out the West

Europe, and its policy toward Russia, is as divided as ever, so at least partial sanctions relief is within Moscow’s grasp. Understanding the import of this year’s European elections – elections that could bring about the eurozone’s demise – Russia will support anti-establishment and Euroskeptic forces and exploit divisions on the continent through cyber attacks and propaganda campaigns.

France, Italy, Austria and Greece will end up seeking a more balanced relationship with Russia, while countries that tend to be more vulnerable to its vagaries – Poland, Romania, the Baltics and Sweden – will band together to fend off what they see as potential Russian aggression. Germany will try to play both sides, something that will be increasingly difficult to do as it also fights to keep the eurozone intact. Germany’s distraction will, in turn, enable Poland to emerge as a stronger leader in Eastern Europe, extending political, economic and military support to those endangered by the West’s weakened resolve.

That is not to say that Russia will be entirely unconstrained. Though Washington appears somewhat more willing to negotiate with Moscow on some issues, the United States still has every reason to contain Russian expansion, so it will maintain, through NATO, a heavy military presence on Russia’s European frontier. This is bound to impede any negotiation. Still, Russia will use every means at its disposal – military buildups on its western borders, the perception of its realignment with the United States, the exploitation of European divisions – to poke, prod and ultimately bargain with the West. And in doing so, it will intimidate its neighbors and attempt to crowd out Western influence in its near abroad.

Even a hint of reconciliation between Moscow and Washington will echo throughout Russia’s borderlands. Russia will almost certainly maintain its military presence in eastern Ukraine, but the United States and some European countries will adopt a more flexible interpretation of the Minsk protocols to justify the easing of sanctions. And because this will leave the government in Kiev more vulnerable to Russian coercion, Ukraine can be expected to intensify military, political and economic ties with Poland and the Baltic states.

In fact, the prospect of a U.S.-Russia reconciliation will all but halt the efforts of otherwise pro-West countries — Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia – to integrate into Western institutions, as will the growing divisions in Europe. These countries will not fully ally with Russia, but they will be forced to work with Russia tactically on economic issues and to soften their stances on pro-Russia breakaway territories.

Just as Ukraine will strengthen security efforts with Poland and the Baltics for security, Georgia will strengthen security efforts with Azerbaijan and Turkey. Turkey will maintain its foothold in the Caucasus and in the Black Sea, but it will also make sure to maintain energy and trade ties with Moscow, lest it jeopardize its mission in Syria.

Russia will remain the primary arbiter in the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan, playing the two against each other to its advantage. And with the European Union’s Eastern Partnership and other EU-led programs likely to suffer from the bloc’s divisions and distractions, Russia will have the opportunity to deepen its influence in the region by advancing its own integration initiatives such as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

All Active on the Eastern Front

With the prospect of things quieting on Russia’s western front, Moscow will try to improve its strategic position on its eastern front. Moscow and Tokyo will slowly try to end a decades-old territorial dispute, and as they do they will enhance relations through major investment and energy deals. (They are even exploring the idea of connecting their countries with an oil pipeline.) Tokyo may also follow the West’s lead in easing sanctions on Russia.

China, too, will pursue similar deals with Russia, albeit for different reasons: It is motivated in part by Russia’s newfound friendship with Japan and in part by the United States’ newfound friction with China. Beijing can be expected to increase cooperation with Moscow this year on energy projects, military coordination (particularly in the Arctic) and cyber-technology.

Russia will play China and Japan off of each other, strengthening its own position in the region while not fully aligning with either. Russia will also continue to build up trade linkages with South Korea while maintaining ties to North Korea as the nuclear threat it poses grows.

Trouble at Home

For all the opportunity Russia has abroad in 2017, it will have perhaps even more challenges at home. Even if it pulls itself out of recession, it still faces a prolonged period of stagnation, and the government will have to adhere to a conservative budget until oil prices rise meaningfully again. The Kremlin will continue to tap into its reserve funds and will rely more on international borrowing to maintain federal spending priorities.

Russia’s regional governments are even more financially vulnerable; they will have to depend on the Kremlin or on international lenders for relief. This reliance will only add to existing tensions between the central and regional governments, tensions that will compel the Kremlin to tighten and centralize its control.

What economic relief does come the federal government’s way will not trickle down to the Russian people, who will continue to bear the brunt of the recession. Protests will take place sporadically throughout the year, and the Kremlin will respond by clamping down on unrest through its security apparatus and through more stringent legislation. The Kremlin will, however, increase spending on some social programs later in the year ahead of the 2018 presidential election.

As the government becomes more authoritarian, power struggles among the security forces, liberal circles, energy firms and regional governments are bound to ensue. President Vladimir Putin will try to curb the power of his potential challengers, particularly Rosneft chief Igor Sechin and his loyalists in the Federal Security Service, through various institutional reorganizations. Restructuring, of course, will entail occasional purges and appointments of loyalists, the ultimate purpose of which is to consolidate power under Putin. His grabs for power, however, will isolate him, and in his isolation he will have fewer and fewer allies.

The Hallmark of Central Asia

Instability, as is so often the case, will plague Central Asia in 2017. Such is the hallmark of a region marked by weak economies, the near constant threat of militant attacks and uncertain political transitions, which include the replacement of long-serving Uzbek leader Islam Karimov, who died in September, a looming succession in Kazakhstan, and presidential elections in Kyrgyzstan. Central Asian governments will manage instability by centralizing power and cracking down on security threats to a greater degree than they have before. This will invite more security involvement from Russia and China, which will compete and cooperate with each other as the situation warrants.

In Kazakhstan, succession concerns and economic stagnation compel the elite to make some critical power plays in 2017, particularly in the energy and financial sectors. These kinds of moves, however, will test the government’s plan for a cohesive succession.

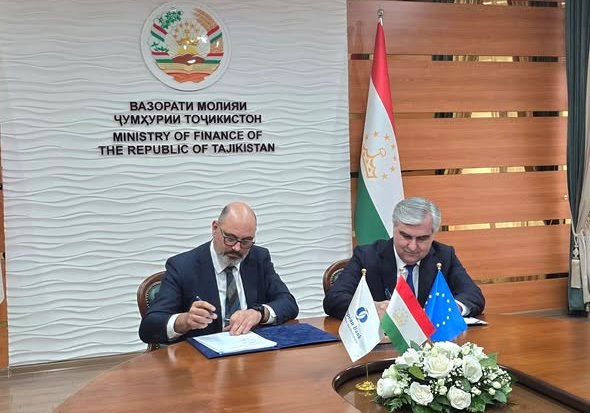

In Uzbekistan, despite its best efforts to stay strategically neutral, the government will find itself cooperating with Russia on energy, military and political issues. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are likely to see intensified security cooperation with China.

2017 Annual Forecast: Eurasia is republished with permission of Stratfor