While a court in Astana tries former economy minister Kuandyk Bishimbayev for murdering his wife Saltanat Nukenova, the Kazakhstani Senate has passed a law strengthening protections for women and children against domestic violence.

The new law, if properly implemented, can hand out much harsher punishments to those who abuse those closest to them. In particular, a term of life imprisonment has been introduced for the murder of a minor child.

In the Face of Widespread Indifference

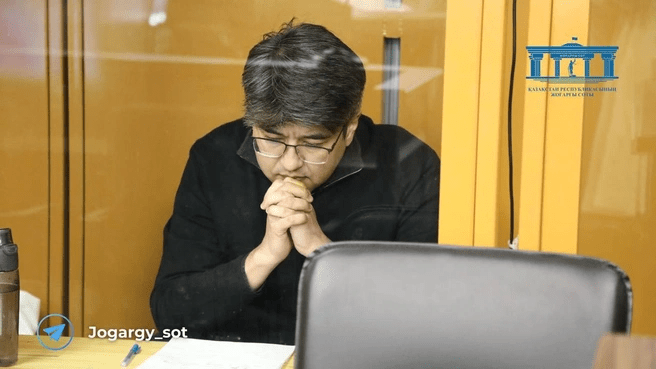

The trial of Bishimbayev – and his relative Bakhytzhan Baizhanov, who is accused of failing to report the murder – has uncovered an uncomfortable truth. Many people already knew that Bishimbayev beat his wife, who died last November. Relatives and close acquaintances of the victim recounted details in court about bruises on Nukenova’s face.

On the day of her death, a number of witnesses saw Bishimbayev arguing with, and possibly beating, Nukenova. Many of these witnesses are employees of the restaurant where the alleged murder took place. Baizhanov admitted under interrogation that he saw blood as Nukenova was laying motionless, but, on the orders of Bishimbayev, had the restaurant’s surveillance tapes deleted, and then drove Nukenova’s phone around the city, so that it would seem later that she was still alive at the time.

According to Baizhanov, he “did not know and did not realize” that Nukenova was dying. However, a forensics expert testified in court that the nature of Nukenova’s injuries indicated serious beatings, not “light slaps and falls,” as Bishimbayev had previously claimed. Examinations confirmed that Nukenova died of multiple brain injuries and a lack of oxygen, likely as a result of asphyxiation.

Will the New Law Help Stop Violence?

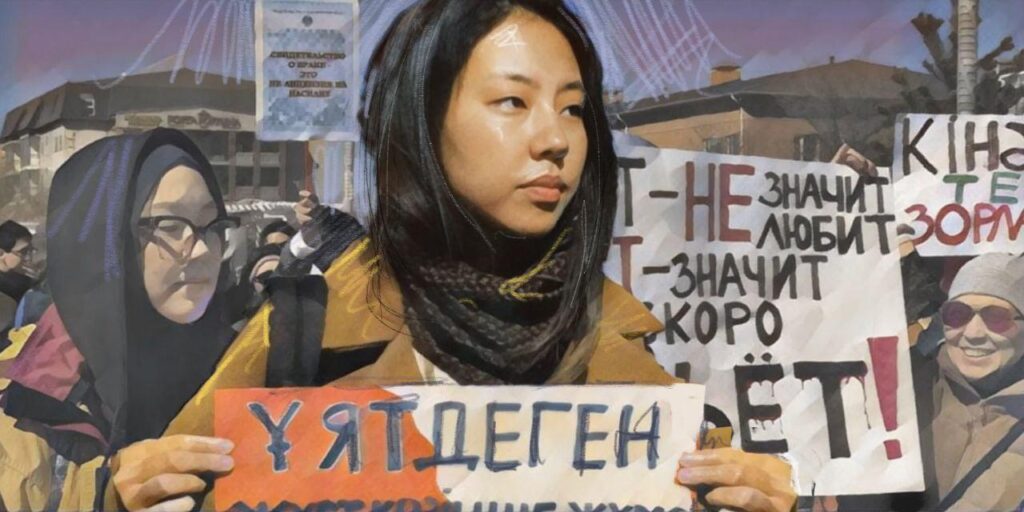

Kazakhstanis are closely following the legal proceedings that have resulted from Nukenova’s death, and are organizing viral online actions and rallies in her memory in cities across Europe. Human rights activists and ordinary Kazakhstanis fought long and hard for domestic violence to be criminalized.

Under the new law, criminal liability will be applied to any intentional infliction of harm to health, however minor. The Code “On marriage (matrimony) and family” establishes the legal status of family support centers and the functions they perform, and establishes helplines for information and psychological assistance relating to women’s and children’s rights. The law also contains many measures aimed at protecting children in public and online.

Activists are still cautious about the new law, and argue that much will depend on its practical application and the amount of funds allocated to it. Support centers for victims of violence receive many calls per day, and physically cannot provide assistance to all those in need.

Central Asia’s Changing Attitudes to Domestic Violence

The other countries in Central Asia face a similar, and perhaps more difficult, situation. Uzbekistan, for example, adopted a law last year to give women and children more protection against domestic violence. Domestic violence in Uzbekistan is subject to administrative and criminal liability, and harassment has been made a crime. The sentences for sexual crimes against children have also been increased, prompted by an increase in the number of such crimes.

Kyrgyzstan has long had a law against domestic violence. It contains recourse to protective orders, which is a progressive concept for Central Asia. In practice, however, according to human rights activists such as Human Rights Watch, the law is incredibly difficult to enforce, and perpetrators often escape punishment.

In Tajikistan there have also been attempts to increase the penalties for domestic abusers. According to a report by the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR), half of all Tajik women have been abused at some point in their lives. The Tajik government, the report says, has not undertaken effective structural reforms, and the law on the prevention of domestic violence has proven to be an ineffective tool.

Last month, while Kazakhstan’s new domestic violence law was going through the Mazhilis (lower house of parliament), the country’s deputy interior minister, Igor Lepekha said that the new legislation would bring about a new challenge for the penal system. “We are already now assuming that about 5,000 persons, and maybe more, [will have to be kept] under these articles in detention centers,” he said.