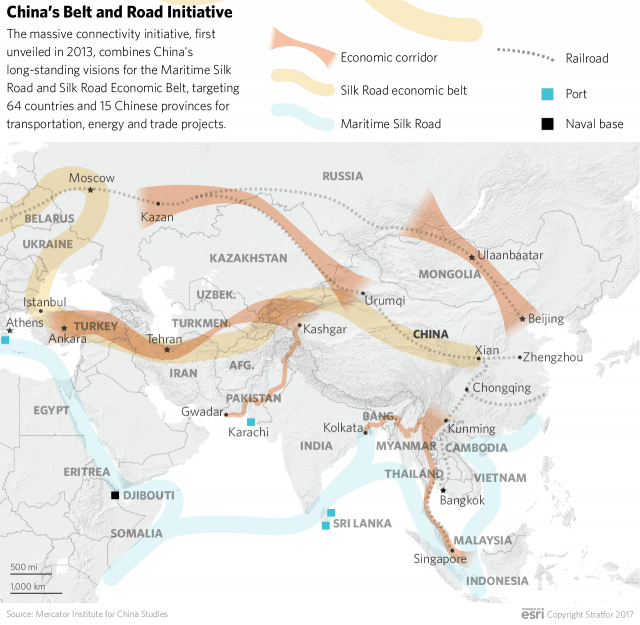

BISHKEK (TCA) — As the summit to promote and showcase China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative finished today in Beijing with China’s new commitment to inject tens of billions of dollars in Eurasian transport and transit projects, we are republishing this article originally published by Stratfor:

The Silk Road has become the stuff of legend. For centuries, the web of trade routes, which expanded to traverse Central Asia and the Mediterranean Sea, connected China to the European Continent, facilitating commerce and cultural exchange. But beyond the economic opportunity that the Silk Road afforded China, it also served a strategic purpose. The Han Dynasty first pursued the routes to defend its heartland from overland invasion and to extend its influence westward. Subsequent rulers in the country continued this mission in one form or another over millennia and through different forms of governance. Mao Zedong, for instance, started the Third Front Movement in the mid-1960s to fortify China’s interior. And today, as the country’s political and economic priorities evolve, its quest to develop its more remote reaches and diversified trade routes while enhancing its access to foreign markets in the region is no less important. With these goals in mind, Chinese President Xi Jinping launched his signature Belt and Road Initiative in 2013.

The program, a modern revival of the Silk Road, has become the centerpiece of Chinese policy since its inception, driving diplomatic, financial and commercial cooperation between China and its neighboring countries. Leaders from 29 countries across Asia and Eastern Europe, along with representatives from 130 nations worldwide, flocked to the summit Xi hosted May 14-15 to commemorate four years of progress on the program. The Belt and Road Initiative, as well as Xi’s summit, is a chance for Beijing to showcase its global ambitions in an era of renewed protectionism, faltering regional economic integration and geopolitical change. China’s aspirations to establish itself at the center of a new global order by increasing its involvement abroad often dominate the discourse over the Belt and Road Initiative, earning it comparisons to the Marshall Plan. Nevertheless, like the Silk Road before it, the Belt and Road Initiative is as much about developing the country’s interior and industry as it is about forging ties beyond its borders.

A Means to Several Ends

China is at a crossroads. Having built an economic empire on low-end manufacturing and exports, the country is now working to shift to a model based on higher-value industries, services and, above all, domestic consumption. Levels of wealth and development vary widely across its vast territory; the discrepancy is particularly pronounced between the bustling metropolises of the Chinese coast and the rural wastelands of the interior. Their enterprises and interests, moreover, not only differ from one to another but also often contradict the central government’s priorities. And all the while, concerns are mounting over the country’s slowing economic growth, not to mention its looming demographic crisis. Managing these issues will be a long and difficult process for Beijing. But in the eyes of the country’s leaders, the Belt and Road Initiative offers a way to at least begin addressing the country’s most pressing social and economic problems.

One of the campaign’s main domestic objectives is to give industrial sectors such as steel and cement production an outlet to offload their excess materials and capacity. As part of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has spearheaded large and resource intensive transportation projects abroad over the past three years, including the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya and the Karakoram Highway linking China and Pakistan. It has even found applications for its burgeoning high-tech manufacturing capabilities in endeavors such as high-speed rail lines, nuclear power plants and telecommunications projects overseas. So far, however, state-owned enterprises and financial institutions have taken the lead in most of China’s Belt and Road ventures, despite Beijing’s desire to encourage growth in its private sector. The heavy reliance on Chinese workers and equipment has also fueled concerns and even resentment among members of the local communities where the projects are underway.

These concerns notwithstanding, the initiative is already producing positive results in China’s interior provinces. Each of the 15 provinces involved in the program has developed its own Belt and Road plan to complement the national blueprint. Several industrial cities in inner China, including Chongqing, Zhengzhou, Wuwei and Wuhan, undertook construction on new freight rail lines to link them to Europe or Central Asia. Other key interior cities such as Kunming, Xian and Kashgar established economic zones, finance and logistical centers, and transport connectivity to facilitate cross-border trade, as well as investment. Though Beijing supplied much of the funding for these projects, provincial governments and businesses also chipped in. Gansu province, for example, worked with China State Construction Engineering Corp. to set up a transportation fund worth 100 billion yuan (about $14.5 billion). The country’s wealthier coastal provinces, such as Guangdong, have had even more leeway to finance investment projects abroad under the Belt and Road Initiative.

Making Connections Abroad

The international ties Beijing forges through its signature policy program will be just as important as the domestic benefits the new infrastructure projects yield. Much as the trade routes of the Silk Road provided imperial China a conduit to convey its influence beyond its borders, the Belt and Road Initiative could give the country greater access to the Eurasian landmass in the coming decades. Beijing has been flexible in implementing this strategy, adapting its approach to suit the specific cultural and political climate of each of its foreign partners. Even so, some countries are more receptive to its advances than others.

Most states participating in Belt and Road Initiative projects were on board with the program’s first step: trade and investment. China has long been a major trade partner and investor for many of these countries. By extending them favorable financing terms through its Silk Road Fund and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing ensured that its partners abroad, many of which are eager to improve their infrastructure, would embrace its proposed ventures. China’s support also provided Eastern European countries such as Poland and Hungary a way to fend off Russia’s influence as the European Union focused on its internal problems. States in Southeast Asia, likewise, were open to Beijing’s investment offers because of their geographic proximity to China and desire to enhance regional integration.

Waning Enthusiasm

As Beijing’s influence in the target countries grew, however, they became wary of the Belt and Road Initiative. Members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), for instance, have found it increasingly difficult to maintain a unified front against China — especially on issues such as maritime disputes — because of varying levels of investment pouring in from Beijing. The predicament may dampen enthusiasm for the Belt and Road Initiative among Southeast Asian countries that want to limit their dependence on China. Similarly, the European Union’s core members have found Beijing’s interest in Eastern Europe to be more competitive than cooperative, something that could influence their policies toward Beijing in the future.

Russia and India, meanwhile, are keeping a close eye on China’s activities in their traditional spheres of influence. Moscow sees Beijing’s investment in Central Asia as a boon for the perennially unstable region, though its growing security presence in the former Soviet territory may inevitably interfere with Russia’s imperatives there. Changes in Russia’s policies, or in its relations with the Central Asian countries, could jeopardize China’s rail and energy projects in the region. Similarly, China could run into complications in its pursuits in South Asia. India vehemently opposed the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — which it views as part of Beijing’s strategy to encroach on the subcontinent — arguing that it would undermine its claims to the contested Kashmir region. In addition, the region’s geographic, political and security challenges will likely impede progress on the CPEC as well as the long-stalled Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar corridor. The projects make easy targets for local separatist or jihadist groups and fodder for political factions leery of China’s increasing sway.

As China’s strategic interests move farther beyond its borders, they will inevitably evolve in keeping with domestic, regional and international developments. The Belt and Road Initiative is just one area in which Beijing may have to adapt its policies and rethink its role on the international stage to accommodate a changing global order. In fact, signs suggest that the shift is already underway: China, which has long adhered to a doctrine of noninterference, is deepening its security ties with Central and South Asian states to combat the threat of Uighur militancy. At the same time, it has begun taking a more proactive approach to conflicts in Myanmar and to territorial disputes in areas such as Kashmir — both areas targeted for Chinese infrastructure. The Belt and Road Initiative, however gradual its progress may be, will test China’s mettle as a rising global power.