Let’s move Aspan Gallery from name to place, from reputation to reality. As one of the Kazakh galleries most visible on the fair circuit, known for its impeccable presentations and strong roster of Central Asian artists, visiting its headquarters in Almaty felt almost inevitable.

It didn’t disappoint. Tucked into the underground floor of a shopping complex in a leafy area of Almaty, where you might catch a glimpse of a stylish passerby balancing a matcha cup before descending the stairs, the gallery unfolds as a quiet enclave.

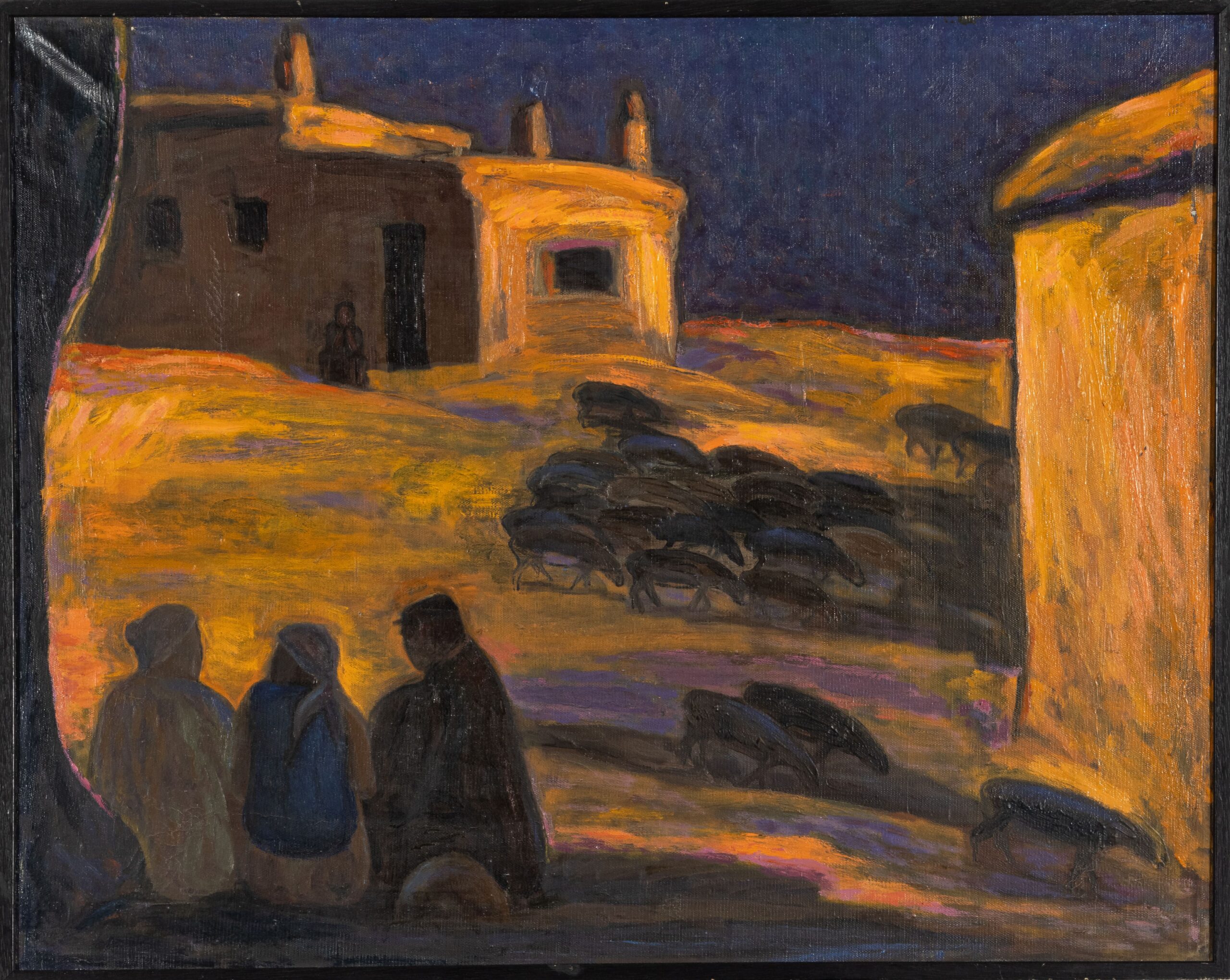

There, Where Wings Grow opens as a multifaceted meditation on the cycles of nature, and particularly on the steppe, explored by several Central Asian artists through ecological, historical, and mythic lenses. What emerges is not a nostalgic portrait of a nomadic past but a layered reflection on resilience and renewal.

At the center of the curatorial vision is Alan Medoev, the archaeologist whose 1960s expeditions uncovered hundreds of sites across the Kazakh steppe. His discoveries challenged Soviet portrayals of the region as an empty expanse and instead presented it as a cradle of memory. The exhibition extends that lineage, tracing how the steppe continues to act as an archive where cultural, personal, and ecological time intersect.

The installation is clean and deliberate: suspended collages, unframed paintings, and subtle shifts in light. Walking through, one feels the exhibition itself has been conceived as a kind of landscape.

Where Wings Grow, installation view; image: Theo Frost

The Interplay Between Distance and Proximity

This quality resonated strongly when encountering the works. At a distance, some pieces seemed almost naïve or casual in their painterly surfaces, but up close, their textures, materials, and embedded details revealed far more intricate worlds.

This is true of Saule Suleimenova’s Plasticographies (two works titled Zhana Omir – New Life and Steppe Romanticism). From afar, they appear to be simple, even sentimental landscapes. Up close, however, they are revealed as collages of discarded plastic: fragments of packaging, commercial logos, counterfeit brands, and old ID cards.

Suleimenova, who grew up in Almaty and trained as an architect before turning to socially engaged art, calls plastic “a treasure” and uses it to question both waste and memory. Within these luminous surfaces are startling details such as embryonic forms and small figures hidden in the texture. These unsettling images evoke new generations coming into a world shaped by waste, suggesting both renewal and ecological crisis.

Steppe Romanticism distills the landscape into minimal horizons and contemplative silence. Yet knowing it is made of plastic prevents forgetting the contradiction, serenity marked by civilization’s residue. It recalls how landscapes themselves operate, inviting from afar but, up close, layered with scars, residues, and histories.

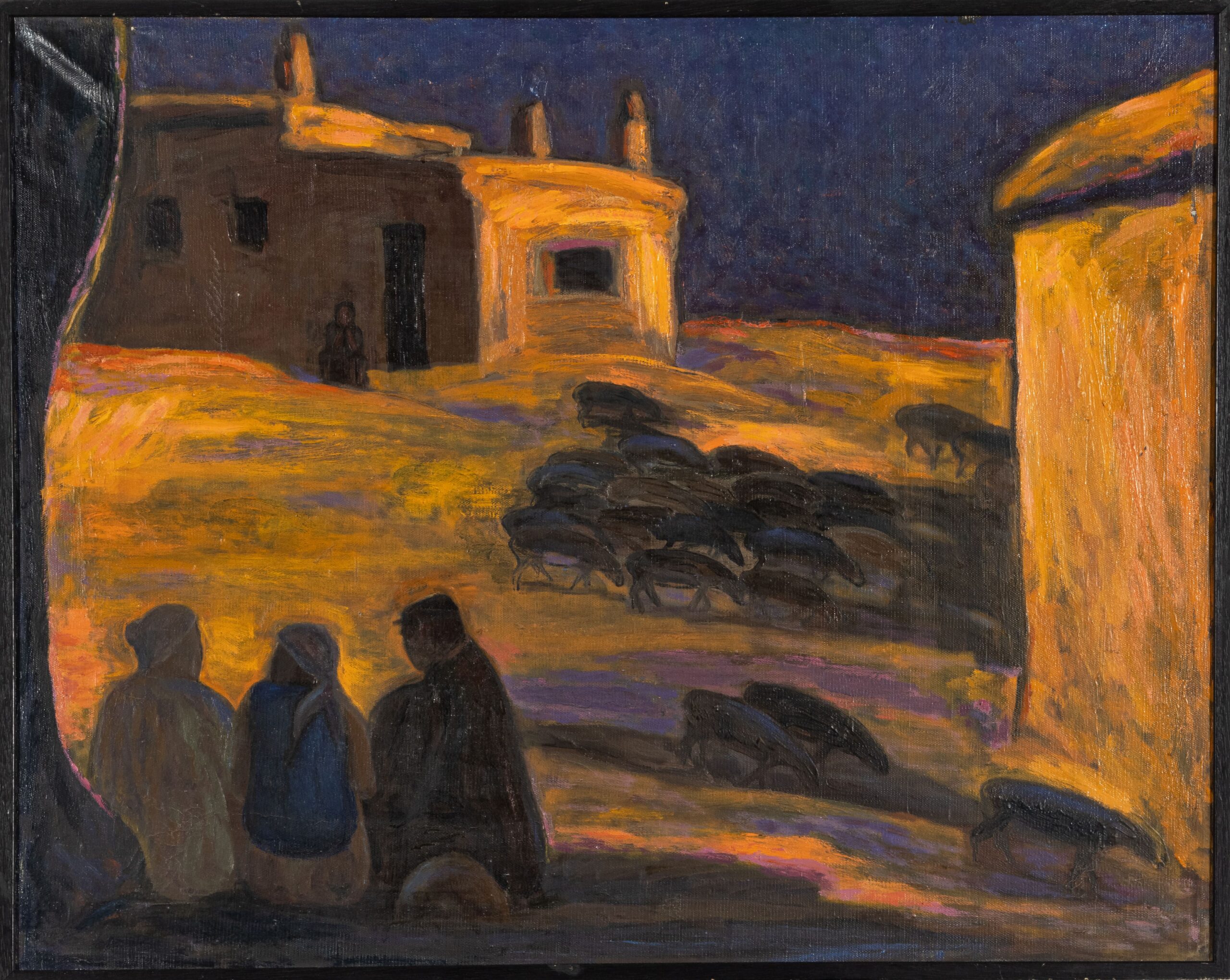

Moldakul Narymbetov, “Untitled”; image: Aspan Gallery.

In a similar spirit, Moldakul Narymbetov’s paintings establish the exhibition’s tone. A founding member of the radical Kyzyl Tractor collective and one of the central figures in Kazakh contemporary art, Narymbetov (1948–2012) was known for fusing folklore, shamanic motifs, and gestural abstraction.

His brushstrokes, dense with fiery movement, make the earth appear both dying and alive. Köktem (Spring) celebrates rebirth through rough, instinctive brushwork that still feels deliberate. Another canvas, Untitled, with its violet and yellow hues, recalls Munch’s haunted skies, yet the subject is a quiet pasture, a landscape impossible to fully grasp. His work, born of the post-Soviet rediscovery of national identity, captures the vitality and volatility of a culture relearning to speak through color.

Resilience in the Face of Adversity

One of the most striking works on view is Ulan Djaparov’s three-minute video Zvezdopad (Falling Stars), created during the Lazy Art Residency. Djaparov, trained as an architect in Bishkek and long active as an artist, curator, and teacher, has always blurred the line between activism and poetics. The video shows children pulling adults into the water, an absurd yet graceful act that alludes to youth movements toppling monuments and to creativity born from collective courage. It is a quiet allegory of change, both generational and moral.

The theme of resilience continues in Bakhyt Bubikanova’s Qanat painting series. Bubikanova (1985–2023), a student of Narymbetov and a rising figure of Kazakhstan’s second avant-garde wave, worked across video, performance, and painting, exploring the paradoxes of modern life. In this series, landscapes are rendered inaccessible by a red fence, a blunt and urgent motif that slices across horizons. The works feel both political and deeply personal, a confrontation between nature and the grids of control. Their quiet unease resonates even more when one recalls that Bubikanova often addressed industrial expansion and environmental degradation.

The photographs by Rustam Khalfin, In Honor of the Rider (created with Zhanat Baimukhametov and Georgy Tryakin-Bukharov), provide one of the exhibition’s most memorable moments. Khalfin (1949–2008), often described as the father of Kazakh contemporary art, was trained in architecture in Moscow before returning to Almaty to teach and experiment with performance, video, and installation. In this piece, a nude man coated in clay sits astride a horse, his body merging with earth and animal. Behind him, a faint rural structure anchors the mythic scene in lived reality. Khalfin’s work, rooted in his lifelong interest in nomadic ontology, visualizes the interdependence of human, animal, and soil. The clay on the rider’s body feels less like a costume than a memory: human flesh as the earth’s own matter.

Askhat Akhmedyarov, “Nomad 4”; image: Aspan Gallery.

That theme of nomadism re-emerges in Askhat Akhmedyarov’s Nomad 4, one of the exhibition’s most urgent interventions. Akhmedyarov, born in western Kazakhstan in 1965 and associated with the Transavantgarde generation, often fuses surrealist imagery with social critique. Here, the traditional nomad is recast as a “new nomad,” displaced not by choice but by circumstance, hanging a painting of a landscape in the open landscape itself.

The work recalls recent evictions in Astana, where urban renewal has meant the demolition of old wooden districts and the relocation of thousands of residents. Many families have spoken publicly about being pressured to leave with inadequate compensation as their homes made way for redevelopment. In this light, Nomad 4 becomes a mirror of forced migration, an image of mobility as injustice. Akhmedyarov’s use of the nomad figure, once a symbol of freedom, now reveals the precarity behind the city’s polished surfaces.

Saodat Ismailova, “Arslanbob”; image: Aspan Gallery.

In a separate room, Saodat Ismailova’s three-channel video Aslanbob closes the exhibition with a lush, meditative reflection on the walnut forests of Kyrgyzstan. Ismailova, born in Tashkent in 1981 and now one of Central Asia’s most internationally recognized artists, works in film and installation to connect myth and environment. Drawing on the legend of a saint who nurtured a seed that grew into the vast forest, Aslanbob reflects on intergenerational responsibility.

What binds these diverse works is their shared reflection on landscape, not as picturesque scenery but as contested terrain. The title Where Wings Grow crystallizes the exhibition’s paradox: to grow wings, one must first be rooted. Yet in Kazakhstan today, both flight and roots are precarious. By turning to the land, these artists seek to reimagine a future where art, ecology, and identity remain intertwined.