Despite having significant uranium resources, Tajikistan does not plan to build a nuclear plant anytime soon, if it all. Quite aware of that, Kazakhstan – Dushanbe’s ally in the Russian-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) – is reportedly eyeing Tajikistan’s uranium. But why?

“I would rather earn a profit from the resources of others than my own,” John D. Rockefeller, a prominent industrialist, is often paraphrased as saying. Policymakers in Astana could soon begin implementing such a strategy in regard to uranium.

Kazakhstan is the largest producer of natural uranium worldwide. In 2022, the energy-rich nation produced the largest share of uranium from mines (43% of world supply), followed by Canada (15%) and Namibia (11%) (ref). In spite of that, Astana could eventually start purchasing the radioactive element from Tajikistan.

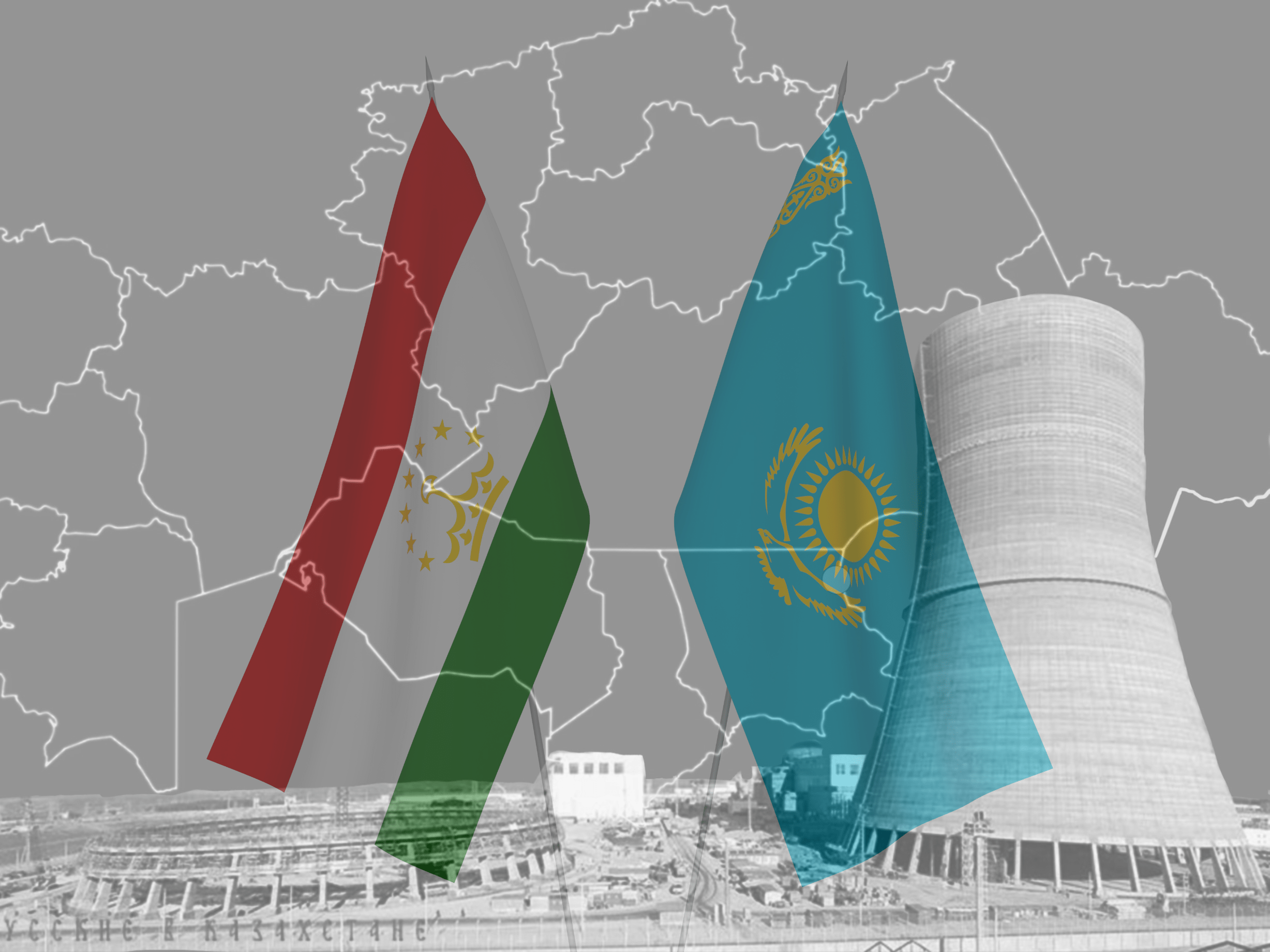

On August 22, following Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s visit to Dushanbe, the Tajik Rare-Earth Metals Company, TajRedMet, and Kazakhstan’s national atomic company, Kazatomprom, signed a memorandum of understanding and cooperation in the extraction and processing of uranium and rare-earth metals. Signing such a protocol aligns with Astana’s ambitions to build a nuclear power plant in the country. In that context, Kazatomprom – the world’s largest uranium producer – is likely seeking to play an active role in producing uranium fuel for the proposed nuclear plant.

Given the global resurgence of nuclear energy and the ensuing “race for uranium,” Kazatomprom is keen to assess the current status of Tajikistan’s uranium reserves, and, if feasible, expand its resource base. Uranium is considered one of the main natural resources of Tajikistan. It is believed that the first atomic bomb developed by the Soviet Union contained raw materials from Tajikistan. But after the collapse of the USSR, uranium mining was curtailed in the mountainous country.

According to various estimates, 14% of the world’s reserves of uranium are located on the territory of the landlocked country of around 10 million people. But compared to other nations, Tajikistan does not have significant uranium mining operations, meaning its uranium deposits remain underdeveloped. However, the fact that Russian companies are interested in exploration and mining of uranium in the Tajikistan suggests that Kazatomprom might have serious competition. It is entirely possible that other foreign corporations will also eventually join the “race for uranium” in Tajikistan.

Meanwhile, Kazakhstan will almost certainly be inclined to consolidate its own uranium market. In terms of uranium production in the largest Central Asian state, the Russian State Nuclear Energy Corporation Rosatom is the leader due to its shares in five enterprises operating in Kazakhstan. Since Astana aims to develop closer ties with the West, it is no surprise that France is looking to strengthen its position in the energy-rich country, particularly in its nuclear and uranium sectors.

Russia and China are unlikely to give up easily on their ambitions to preserve their influence in the Central Asian nation, however. In 2022, Kazakhstan exported around half of its uranium to China. From January to October 2023, Astana shipped uranium worth $922.7 million to the People’s Republic, while over the ten months of 2023, Kazakh uranium exports to Russia reached $1.2 billion. Thus, due to its proximity to Moscow and Beijing, Kazakhstan will likely remain in Russia’s and China’s geo-energy orbit for the foreseeable future.

That, however, will not prevent Astana from developing its nuclear sector.

“Kazakhstan is a uranium producing and exporting country, so we are obliged to use this advantage to the maximum,” Kazakhstan’s Vice-Minister of Energy, Sungat Yessimkhanov said on April 16.

The problem for Kazakhstan is that out of the 14 uranium mining companies in the country, only two are 100% owned by Kazatomprom. Almost half of Kazakhstan’s uranium is reportedly extracted by foreign companies. Since Kazakhstan, unlike Tajikistan, aims to advance its nuclear capabilities and potentially build a nuclear power plant, it will need to secure a sufficient supply of uranium for this purpose. In other words, if Astana continues exporting all the uranium it produces, it will potentially have to import the element from Tajikistan to make its nuclear power plant feasible.

A referendum on the construction of the nuclear power plant is planned to take place on October 6. This decision reflects the government’s push to address the country’s growing energy needs, although the issue remains sensitive as a consequence of the painful history of the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site in northeastern Kazakhstan, where more than 450 nuclear tests were carried out during the Soviet period. Despite the site’s closure in 1991, its effects continue to resonate strongly with the local population.

However, recent opinion polls suggest that a majority of respondents (53.1%) support building a nuclear power plant. Therefore, it is highly probable that referendum will succeed, and Kazakhstan will soon acquire a strategically important nuclear facility, the construction of which may cost up to $15 billion.

As to who will build the nuclear power plant – whether Rosatom, Chinese or Korean companies, or Western corporations – this is another sensitive and serious geopolitical issue.