In the aftermath of the terrorist attack in Moscow, the media has once again been saturated with discussions about the terrorist group Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISKP), also known as ISIS-Khorasan and “Wilayat Khorasan.”

At this point, most of the coverage has focused on the Afghan wing of Islamic State, and not its other “wilayats,” such as on the Arabian Peninsula, “Wilayat Sinai” (Islamic State – Sinai Province) or “Wilayat Caucasus” (Islamic State – Caucasus Province).

The international media covering the ISKP attack in Moscow, including journalists from Russia, widely speculated that the terrorist group is looking at Central Asia as its next base. Such media coverage included a variety of sentiments indicating that Central Asia should be worried. Reports have suggested that the alliance of Central Asian leaders with Moscow makes them look weak in the eyes of ISKP and that the terrorist threat emanating from Central Asia has become a point of weakness for the Putin regime. It has also been suggested that Islamic terrorism in Central Asia remains a real problem for the FSB, and even though the FSB has extensive experience in fighting extremists in the Caucasus, having committed enormous resources to the issue, Central Asia is a blind spot. Alarm bells sounded that regional jihadist groups have become more powerful.

Thus, the terrorist attack in Moscow significantly increased media attention on ISKP in the context of Central Asia. Overall, the ISKP theme fits into existing narratives regarding threats to the southern border of the CIS.

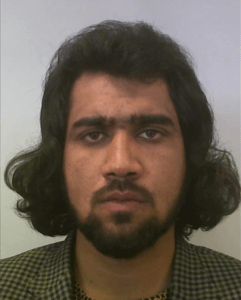

Sanaullah Ghafari, Emir of ISIS-K; image: rewardsforjustice.net

The more likely reality is that in Central Asia, ISKP has been more of a challenge to regional security than an existential threat. In recent years, the region has been broadly successful in dealing with threats from Afghanistan.

How real of a threat is the ISKP?

A very narrow circle of experts can give a truly objective assessment of ISKP. Information about ISKP membership is contradictory and seemingly based on political considerations. As such, it is difficult to back these up with statistics. The number of fighters reported vary greatly from 2,000 to several tens of thousands.

What remains indisputable are two facts: 1. Despite measures declared by the Taliban to eliminate the ISKP, terrorist acts by the group are still recorded throughout Afghanistan, and 2. The group lacks a serious infrastructure in Afghanistan. The activity of ISKP in Afghanistan consists of carrying out targeted, low-level terrorist acts, mainly against local Hazara Shiites.

Based on the assessments of the UN Afghanistan monitoring team, the potential of ISKP success looks dubious. In its reports, UN experts point to a decrease in ISKP activity in Afghanistan. Recently, the UN has avoided estimating the size of the group, but previous estimates put it at 1,500-2,200 fighters. At the same time, according to a UN report in January, “ISKP adopted a more inclusive recruitment strategy, including by focusing on attracting disillusioned Taliban and foreign fighters.” Taliban officials, meanwhile, tend to play down the situation. According to the press secretary of the Afghan Ministry of Interior Affairs, as quoted by the Afghan site TOLOnews, the number of incidents fell 40% in 2023 versus the year before although their geographic footprint included the provinces of Badakhshan, Baghlan and Herat and “even the capital.” The Taliban admit that there are IS cells in the country, with which they claim to be successfully fighting.

In the end, geopolitical competition for influence in the region, also called the latest round of the Great Game for Central Asia, will likely include a component on countering terrorism. On the one hand, as Russia becomes increasingly concerned about the possibility of losing its influence in the region to China and the West, carrying out anti-terrorism measures abroad could ultimately become its ‘Trojan horse.’ The surge in xenophobia against people from Central Asia and Islamophobia seen inside Russia only strengthens these trends. On the other hand, Moscow is increasing pressure on countries in the region due to what it claims to be the terrorist threat to Russia emanating from Central Asia. In this regard, the choice of using Tajik citizens for the terrorist attack likely comes from the fact that they are the most convenient. Tajikistan ranks first in terms of labor migration to Russia. It borders Afghanistan, where Tajiks represent the second largest ethnic group. Tajik society is still dealing with the consequences of the civil war of the 1990s in which religion and Islamic institutions played an important role. Additionally, the Tajik state tightly controls religious life in the country. Note that the Jamaat Ansarullah group, also known as Tehrik-i-Taliban Tajikistan that operates in northern Afghanistan, is purely Tajik.

It seems that currently the ISKP’s numbers and bases in Afghanistan as well as in the Central Asian countries are not rising. The discussions surrounding the group should be taken in the context of intensifying geopolitical conflicts, with ISKP being turned into a “formidable regional structure” and thus gaining notoriety in the world.

Aidar Borangaziyev is an Open World Foundation expert and a consultant for the Investment Group, ACME.