For France – a country that gets around 70% of its electricity from nuclear energy – Kazakhstan’s decision to build its first nuclear power plant presents an ideal opportunity to strengthen economic ties with the Central Asian state. For Astana, potential cooperation with French nuclear corporations could help reduce dependence on Russia and its State Nuclear Energy Corporation, Rosatom. But will things really go that smoothly?

In November 2023, following the meeting between Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and his French counterpart Emmanuel Macron, in Astana, it became clear that, for Paris, establishing a strong nuclear partnership with the largest Central Asian nation was the top priority with regard to Kazakhstan. The following year, Tokayev flew to Paris for another round of talks with Macron. Reports suggest that nuclear cooperation was once again one of the key topics the two leaders discussed.

On November 4, a day prior to the Macron-Tokayev summit, French and Kazakh officials signed 24 documents on cooperation worth $2 billion. Unsurprisingly, energy was a central focus. Kazakhstan agreed to establish closer ties with two French nuclear giants: Orano and Électricité de France (EDF).

According to Gabidulla Osspankulov, Chairman of the Investment Committee of the Kazakh Foreign Ministry, Orano’s great experience in uranium extraction makes it a key partner for Astana. That is why the former Soviet republic aims to use the company’s technologies and experience in uranium production in Kazakhstan. Ospankulov also expects both Orano and EDF to be part of a consortium that will build the nuclear power plant in the Central Asian country.

Paris, on the other hand, is likely seeks to not only be involved in the construction of the nuclear facility, but also to get Kazakhstan’s spent nuclear fuel for reprocessing. In exchange, Astana – possibly the world’s largest uranium producer – can increase its uranium exports to France. From the French perspective, such an arrangement would be very beneficial, especially after Niger’s military government revoked Orano’s permit to operate at its Imouraren uranium mine – one of the biggest in the world. The problem, however, lies in geography and logistics.

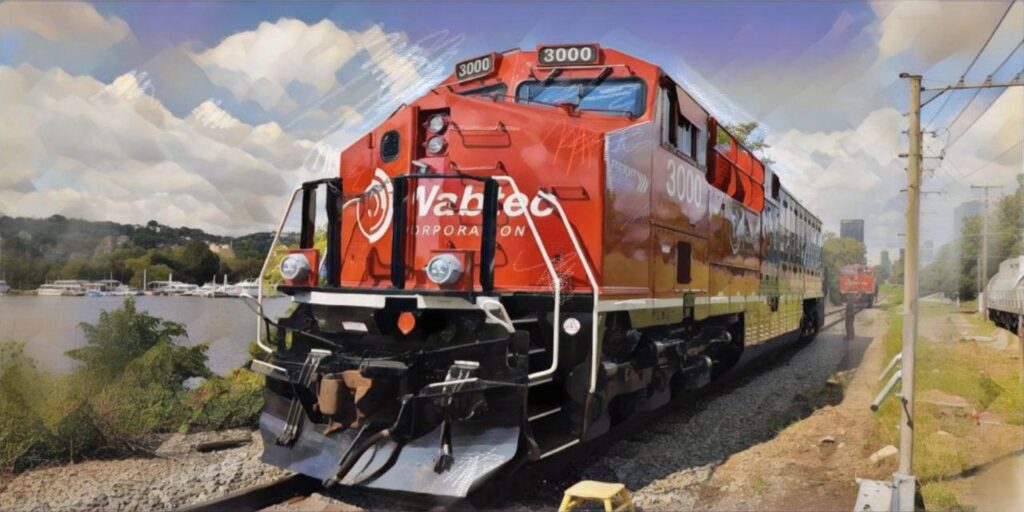

On the eve of the Macron-Tokayev summit, the French train manufacturer Alotom and the Kazakhstan Temir Zholy Electric Locomotive Assembly Plant signed a deal on the supply of 117 French-made freight electric locomotives, weighing up to 9,000 tons, to the former Soviet republic. Will they be used for the transport of Kazakh uranium to France?

Russia and China, as the Central Asian nation’s giant neighbors, could easily, under any pretext, block the transport of Kazakh nuclear materials through their territories to Europe. Rail remains the dominant mode of transport for Kazakhstan’s uranium exports, but its reliance on Russian and Chinese routes poses a strategic challenge for Astana.

To avoid using the two nations’ railways, Astana would have to boost uranium and potentially also spent nuclear fuel exports via the Caspian Sea Route, primarily through the Middle Corridor. It is, therefore, no surprise that modernization of this network remains Kazakhstan’s primary objective. But without reaching a “nuclear deal” with Russia and China, this route could also become problematic, as Kazakhstan risks worsening relations with Moscow and Beijing.

Quite aware of that, Tokayev stated before his trip to France that the first Kazakh nuclear power plant “must be built by an international consortium.” In other words, he likely aims to apply his well-known “multi-vector” foreign policy to the construction of the nuclear facility in Kazakhstan. That, however, does not mean that Astana will hesitate from strengthening economic and energy cooperation with Paris.

As Tokayev wrote in his article for the French Le Figaro newspaper, “after it decided to build the first nuclear power plant, Kazakhstan can support the French nuclear industry while retaining its status as a reliable partner.” That is exactly what France, which recently reached similar arrangements with Serbia – another country Tokayev is expected to visit in the near future – hopes to achieve.

While in Kazakhstan France eyes uranium, in the Balkan nation it aims to get lithium and other raw materials, and potentially to build small modular nuclear reactors. More importantly, Belgrade has recently signed a deal with Paris for the purchase of twelve French-made Rafale jets, although without the Meteor missiles. Interestingly enough, in November 2023, following the summit between Macron and Tokayev in Astana, French media reported that Kazakhstan also eyed Rafale jets.

Indeed, there are similarities between the deals France reached with Serbia and those it hopes to sign with Kazakhstan. But there are significant differences, too. Serbia, unlike Kazakhstan, is not Russia’s ally in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and it does not share a border with the Russian Federation. Also, the Southeast European nation is firmly in the Western geopolitical orbit, which gives Moscow very little room for maneuver there.

Kazakhstan’s proximity to both Russia and China forces the authorities in Astana to maintain a delicate balance, avoiding confrontation with its neighbors while developing closer economic and energy ties with the West. But will Moscow and Beijing view Astana’s nuclear ambitions favorably?