Kazakhstan Faces Turbulence as External Pressures Mount

Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s largest economy, is facing a convergence of pressures, from currency depreciation and geopolitical turmoil to volatile oil markets and contentious fiscal reforms, that are testing its economic resilience.

Geopolitical Pressures Escalate

By mid-2025, it had become increasingly apparent that Kazakhstan has limited capacity to influence global geopolitical dynamics. Like many “middle powers,” the country must adapt to the actions of larger states, whose unpredictable decisions continue to exert downward pressure on the tenge and fuel inflation.

On July 28, U.S. President Donald Trump shortened a previously issued 50-day ultimatum to Russian President Vladimir Putin, giving him just 10-12 days to agree to a peace deal with Ukraine. This development added to the mounting uncertainty already impacting Kazakhstan’s economy.

As previously reported by The Times of Central Asia, analysts warn that Trump’s secondary sanctions, 100% tariffs targeting Russia’s trading partners, could potentially be extended to Kazakhstan and other Central Asian economies. Though Kazakhstan is not among Russia’s largest trading partners, its economic links to Moscow are still substantial. The country relies heavily on imports from Russia, including electricity, gasoline, food, and medicine.

Adding to the pressure, on July 7, Trump announced a 25% tariff on Kazakhstani goods, effective August 1, 2025. While $1.8 billion of Kazakhstan’s $2 billion in exports to the U.S. (mostly oil, metals, and rare earth elements) are exempt, the move has nonetheless rattled Kazakhstan’s already fragile industrial sector and spooked investors.

Oil price instability, largely driven by Western efforts to curtail Russian exports, also poses a major risk. Oil revenues make up the bulk of Kazakhstan’s export income and are a key source of budget financing.

Further complicating matters, new Russian restrictions require foreign tankers to obtain Federal Security Service (FSB) approval before accessing key Black Sea ports. This affects the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which handles more than 80% of Kazakhstan’s oil exports and is partly owned by U.S. firms Chevron and ExxonMobil. Reuters estimates the new rules could disrupt over 2% of global oil supply.

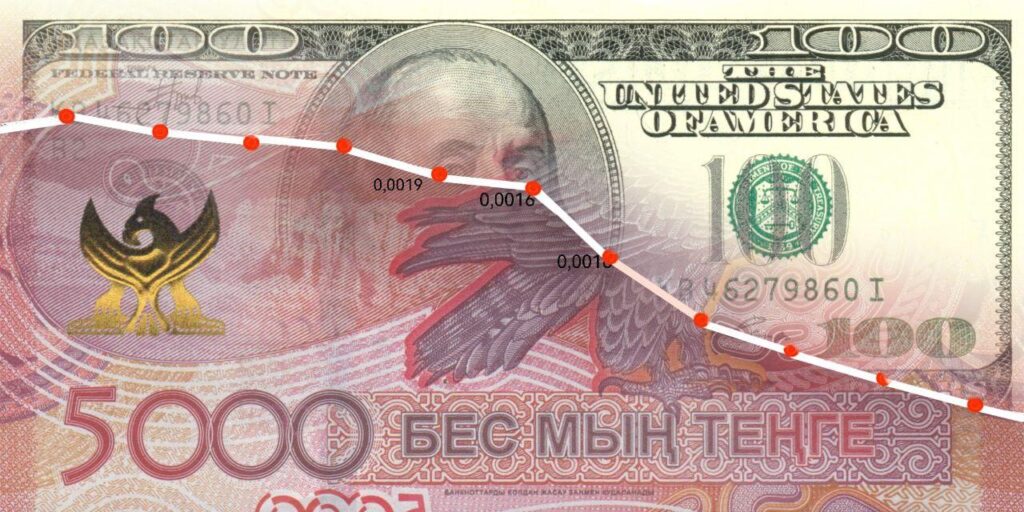

Tenge Hits Historic Low

As of July 28, the tenge dropped to a record low of 544.87 per U.S. dollar. The depreciation is driving up the cost of imports, an acute problem in an import-dependent economy, pushing more families to spend over half their income on food.

Companies with debt obligations in U.S. dollars are also seeing their liabilities grow, worsening the investment climate and prompting firms to scale back on planned expansions.

Central Bank Warns Against Intervention

National Bank Chairman Timur Suleimenov cautioned against government intervention in currency markets, stating that past administrative controls led to abrupt and damaging devaluations.

Suleimenov blamed rising fiscal injections and an 18% increase in money supply for the tenge’s vulnerability. He warned that unless GDP and industrial output keep pace with monetary growth, currency pressure will persist. Although Kazakhstan has $52.2 billion in reserves to mitigate speculative shocks, the governor insisted that intervention should be reserved for market distortions, not fundamental shifts.

Structural Trade Imbalances Deepen

Economist Yernar Serik noted via his Telegram channel, Tradereport, that growing imports of foreign equipment, driven by industrial modernization, are compounding exchange rate pressures. In June 2025 alone, domestic firms spent 652 billion KZT ($1.2 billion) on machinery, a 47% increase from May and 35% higher year-on-year.

Serik also highlighted a deteriorating trade surplus: from $9.5 billion in January-May 2024 to just $6 billion in the same period of 2025. While exports fell 9% to $29.8 billion, imports rose to $23.7 billion. “This trade pattern means Kazakhstan now earns less foreign currency while spending more of it,” Serik said. “The weakening of the tenge isn’t a conspiracy; it reflects the laws of supply and demand.”

Fiscal Reforms Spark Backlash

In a bid to stabilize the economy, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed a new Tax Code on July 18, introducing a 16% standard VAT rate and setting reduced rates for medicine and healthcare services from 2026.

The reforms have triggered strong resistance from the business community. Industry associations and entrepreneurs argue that the changes will stifle business activity, increase administrative burdens, and raise the risk of corruption.

“Due to the increased tax burden, businesses will raise prices, rents will climb, and consumer demand will fall,” warned Berik Zairov, chair of the Union of Independent Businesses of Kazakhstan. Experts also forecast a further drop in small business numbers and a negative impact on wages and investment.

Economic Crossroads: Kazakhstan Faces Prolonged Volatility

As Kazakhstan navigates this storm of external shocks and domestic challenges, the coming months will test the government’s ability to balance fiscal discipline with economic support. While officials are betting on cautious monetary policy, structural reforms, and resilient oil exports to prevent a deeper crisis, the country’s dependence on external markets leaves it exposed to forces beyond its control. Without a decisive shift in trade dynamics or geopolitical relief, Central Asia’s largest economy may face a prolonged period of volatility that reshapes its growth trajectory.