Using the emerging technology of color photography, Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky (1863–1944) undertook several photographic expeditions to capture images of the Russian Empire. Most of his work took place between 1909 and 1915, though some photographs date as early as 1905. At the time, the Russian Empire stretched roughly 7,000 miles east to west and 3,000 miles north to south. It encompassed one-sixth of the Earth’s land surface, making it the largest empire in history, spanning what are now eleven time zones.

Abutment for a dam and house belonging to the government. [Kuzminskoe] Prokudin-Gorsky, Sergey Mikhaylovich, 1912

Tsar Nicholas II supported Prokudin-Gorsky’s ambitious endeavor by granting him travel permits and access to various modes of transportation, including trains, boats, and automobiles. His journeys are preserved in photographic albums that include the original negatives. One album also features miscellaneous images, including scenes from other parts of Europe. The photographs capture a broad array of subjects: religious architecture and shrines (churches, cathedrals, mosques, and monasteries); religious and secular artifacts (such as vestments, icons, and items linked to saints, former Tsars, and the Napoleonic Wars); infrastructure and public works (railroads, bridges, dams, and roads); a variety of industries (including mining, textile production, and street vending); agricultural scenes (like tea plantations and field work); portraits, which often showed people in traditional dress, as well as cityscapes, villages, natural landscapes, and blooming plants.

Besides being a photographer, Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky was a chemist who is renowned for his pioneering contributions to color photography in the early 20th century. In 1901, he traveled to Berlin to study photochemistry before returning to Russia, where he outfitted a railroad car as a mobile darkroom with the support of Tsar Nicholas II. As he traveled across the Russian Empire, he documented its people and landscapes, eventually earning recognition in Russia, Germany, and France. In 1906, he was appointed head of the photography section of Fotograf-Liubitel, Russia’s leading photography journal. One of his most famous works is a color portrait of Leo Tolstoy, taken in 1908.

“By capturing the result of artistic inspiration in the full richness of its colors on the light-sensitive photographic plate, we pass the priceless document to future generations,” wrote Prokudin-Gorsky. As a nobleman, inventor, professor, and pioneer of color photography in Russia, Prokudin-Gorsky had a deep sense of national identity and heritage. Although he was unable to complete his grand project due to the outbreak of World War I and increasing social unrest across the Russian Empire, he still managed to capture photographs in regions such as the Urals, Siberia, Crimea, Dagestan, Finland, and Central Asia, as well as along the Volga and Oka rivers. Unfortunately, much of his photographic archive was lost in the aftermath of the 1917 Revolution.

Prokudin-Gorsky created unique black-and-white negatives using a triple-frame method, taking three separate exposures through blue, green, and red filters. This technique allowed the images to be printed or projected in color, often for magic lantern slide presentations. The complete collection of 1,902 triple-frame glass negatives has been digitized, including approximately 150 images not included in his original albums. Each digitized image displays all three frames. Additionally, the individual frames, typically the green-filtered center shot, are also available, enabling closer inspection of the details.

Fishing settlement, Prokudin-Gorsky, Sergey Mikhaylovich, 1915

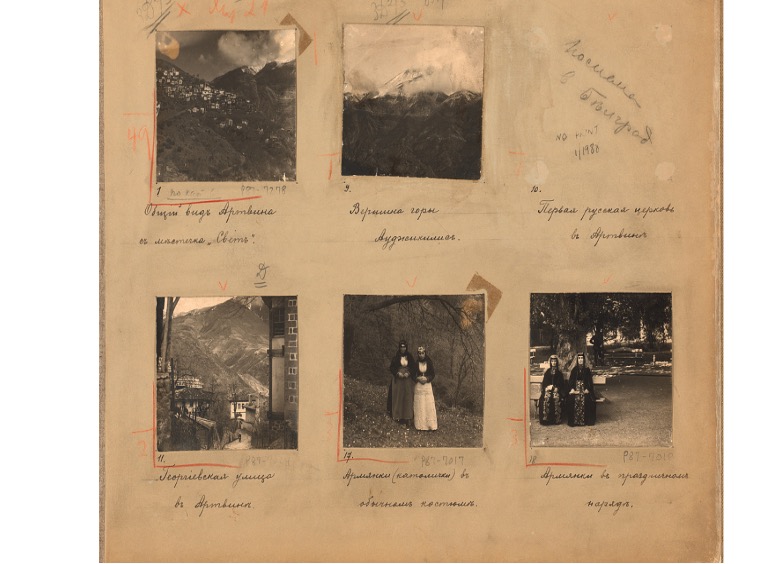

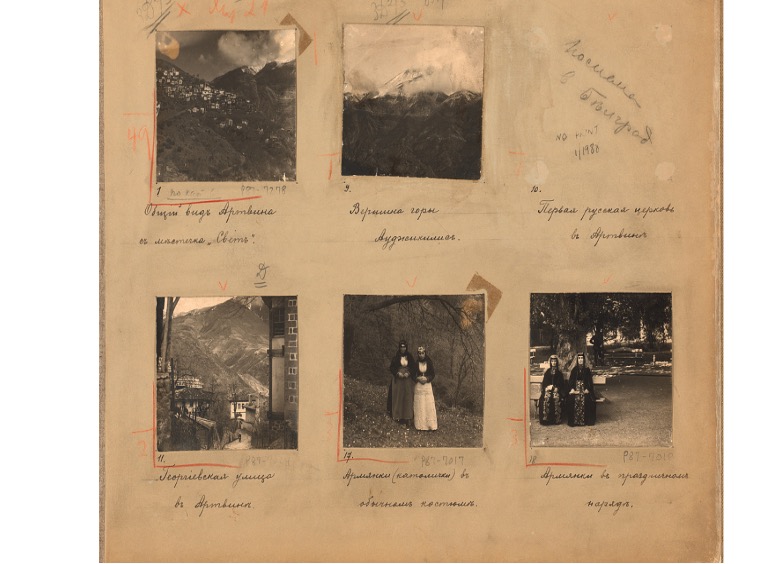

The Library of Congress holds twelve albums (in fourteen volumes) that Prokudin-Gorsky compiled as visual notebooks documenting his travels and research. Digitized pages from these albums allow modern viewers to retrace the same routes Prokudin-Gorsky followed over a century ago, viewing the photographs in the original order he intended. The pages display all 2,433 contact prints contained in the albums, along with their original Cyrillic captions and annotations. Each page typically includes six prints, though some contain blank spaces where images were removed long ago.

Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky and two men in Cossack dress are seated on the ground

A page from Prokudin-Gorsky’s photo album of Europe containing images of Venice, Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky

Prokudin-Gorsky also traveled to Italy, Finland, and Yasnaya Polyana — Leo Tolstoy’s estate in Russia — to photograph subjects of cultural and historical significance, including Tolstoy himself. These travels were most likely undertaken before he began his larger project to document the Russian Empire.

A page from Prokudin-Gorsky’s photo album of the Caucasus containing photos of Artvin (in present-day Turkey), as well as its surrounding mountains and some of its Armenian inhabitants, Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky, between 1900 and 1920

From the photographs he took a century ago, we can clearly see the face of society at that time.

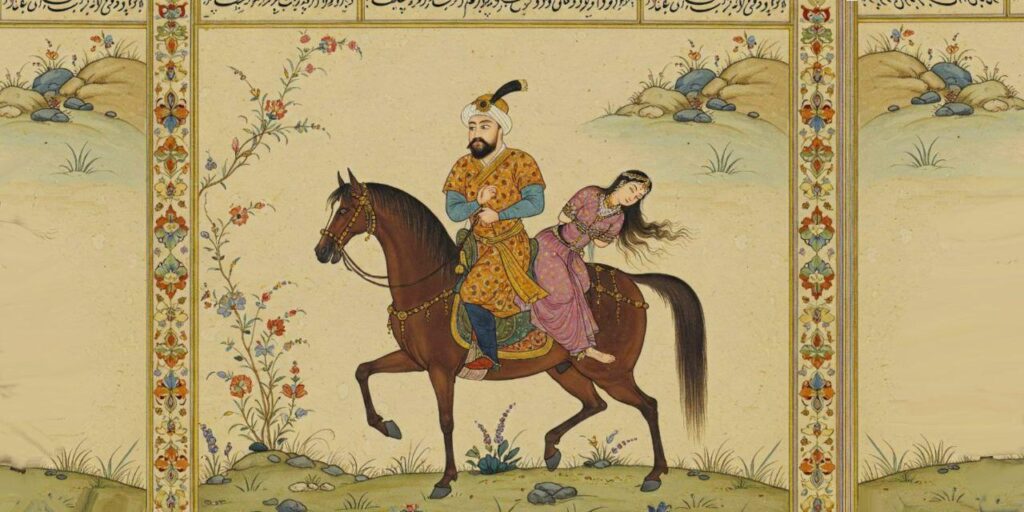

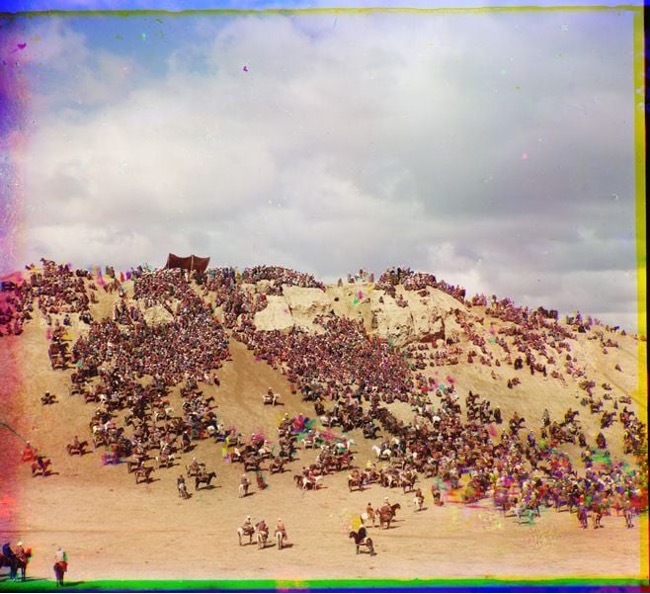

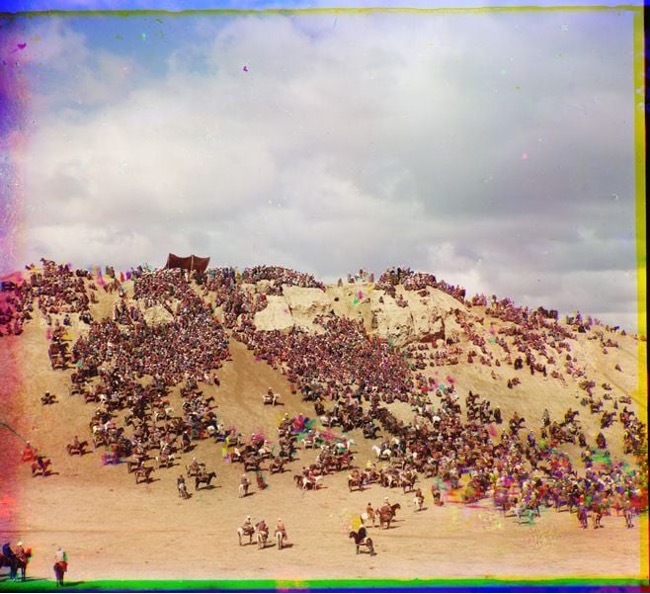

Bayga, near Samarkand, Turkestan, Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky, between 1905 and 1915

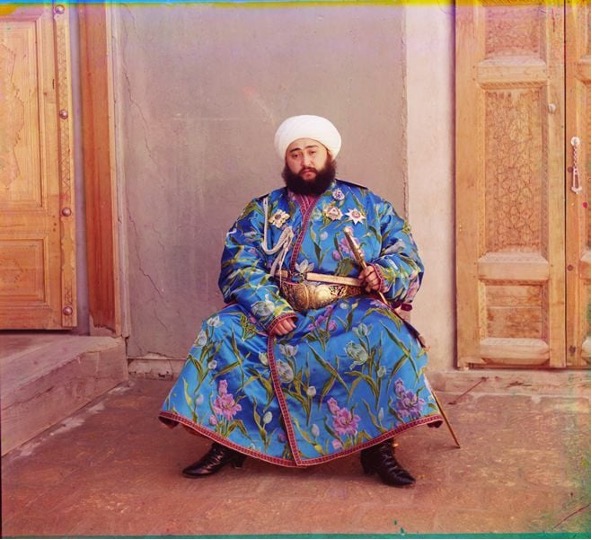

Isfandiyar Jurji Bahadur, Khan of the Russian protectorate of Khorezm (Khiva, now a part of modern Uzbekistan), Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky, 1910

A watercarrier in Samarkand (present-day Uzbekistan), Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky, 1910

Nomadic Kirghiz on the Golodnaia Steppe in present-day Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky, 1910