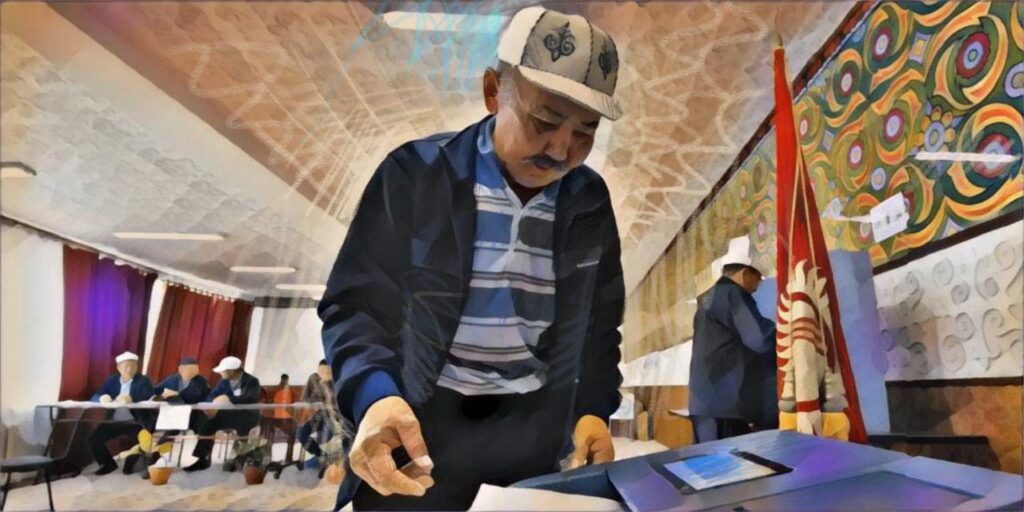

Campaigning for seats in Kyrgyzstan’s upcoming parliamentary elections is underway, and it is already shaping up to be a race unlike anything seen before in Kyrgyzstan. The 467 candidates competing for the 90 seats in parliament have only 20 days to make their cases to voters in their districts. Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov’s government has vowed to keep these elections clean and fair, and threatened severe punishment for those who attempt to cheat in any way.

Uneven Electoral Landscape

The country is divided into 30 voting districts, and in each district, the three candidates who receive the most votes will win seats.

The level of competition varies, depending on the district. Electoral district 11, which is Manas city (formerly Jalal-Abad), has 155,023 eligible voters. Only five candidates are running in the district, three of whom are women. According to new election rules, a woman (or a man) must win at least one of the three seats available in each district.

Name recognition is always important, and especially so in elections with many newcomers seeking seats in parliament. One of the candidates in District 11 is Shairbek Tashiyev, the brother of the current head of the State Committee for National Security (GKNB), Kamchybek Tashiyev. He is almost certain to win one of the seats.

In electoral district 19 in Kyrgyzstan’s northern Chuy Province, with 138,373 eligible voters, there are 25 candidates competing.

The two districts with the largest number of voters, district 15 in the Aksy area of western Kyrgyzstan with 160,218 voters, and district 28 in the Zhety-Oguz area of eastern Kyrgyzstan with 160,181 voters, have, respectively, 15 candidates and 17 candidates. In the districts where there are 15 or more candidates, the three winners might only receive around 10,000 votes, or even less.

The candidates are out meeting with voters, but many are relying on social networks to promote their image and spread their message. Domestic television stations, ElTR and UTRK, are airing candidate debates that “will be distributed regionally, depending on the candidates’ electoral districts.”

Not Running

Eleven of the current 90 deputies in parliament have opted not to run for reelection. Among them are Iskhak Masaliyev – currently in the Butun (United) Kyrgyzstan Party but previously the long-time head of Kyrgyzstan’s Communist Party – the son of Absamat Masaliyev, who was first secretary of the Communist Party of the “Kirghizia” Soviet Socialist Republic from 1985 until independence in August 1991.

Another current member of parliament who is not running is Jalolidin Nurbayev, whose attempt to register was rejected due to two criminal cases having previously been opened against him, one in 2006, the other in 2021.”

A new election rule prohibits people whose cases were “terminated on non-rehabilitating grounds” from being eligible to hold public office. Effectively, this means that any case against them has been closed without declaring the person innocent, but without restoring their reputation, even though they are no longer being prosecuted.

Members of organized criminal groups and their family members have won seats in previous elections.

Back in September 2005, Member of Parliament Bayaman Erkinbayev was shot dead outside his home in Bishkek. A wealthy businessman, Erkinbayev was widely believed to have connections to organized crime.

Some 20 years ago, Ryspek Akmatbayev was allegedly the top kingpin in Kyrgyzstan’s organized criminal world. His brother, Tynychbek, was an MP when he was killed when a riot broke out at a prison he was visiting outside Bishkek. Ryspek ran for his slain brother’s vacant seat in parliament and won the April by-election, but was gunned down a month later while leaving a mosque in Bishkek.

More recently, Iskender Matraimov was elected to parliament in 2015, reelected in 2020, and in the snap elections of 2021. His younger brother, Raimbek, a former Customs Service deputy chief, was allegedly one of the biggest underworld figures in Kyrgyzstan and the subject of several investigative reports. GKNB chief Tashiyev started a crackdown on organized criminal groups in late 2023, and Raimbek fed the country. The CEC finally stripped Iskender of his deputy’s mandate in February 2024.

On November 7, the CEC announced it had denied the registration documents of 34 people, several of whom were rejected because of their connections to organized crime. In total, the CEC refused to register 122 would-be candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections.

Enforcing the Rules

Since the snap elections were first announced in late September, President Japarov and GKNB chief Tashiyev have repeatedly warned that the abuses seen in past elections will not be tolerated. Tashiyev said just days after the date of the early elections was announced that “any fraud will be exposed, and the punishment will be the harshest.”

Since Kyrgyzstan’s inaugural parliamentary vote in 1995, elections have been consistently marred by vote-buying. Speaking at a youth forum on November 10, Japarov said, “We have established strict controls on voter bribery.” One candidate from electoral district 3 has already been caught and disqualified after he arranged a small meeting with some 15 voters and promised them “material rewards” for casting their ballots for him.

The practice of buying votes is unfortunately deeply entrenched in Kyrgyzstan’s parliamentary elections, so while this example is encouraging, it is unlikely to discourage everyone in the country from attempting to bribe people for their vote.

The Field of Candidates

The change from elections decided by party (2007, 2011, 2025, 2020) or partially party lists and single-mandate (2021) to the impending elections decided solely by single-mandate districts has led to an interesting array of candidates. Most of the candidates are politicians or state employees, many are businessmen, several dozen are listed as “unemployed,” there are some bloggers, and a few academics and activists.

Changes to the constitution approved in a national referendum in 2021 transferred most of the political power to the executive branch. However, Kyrgyzstan’s legislative branch has often been weaker in the past than the executive branch, yet deputies were still able to use parliament to carry out changes and keep presidents in check.

Parliament has been relatively quiet since the 2021 elections, outside of the scandals that surrounded some of the 27 deputies whose mandates were revoked during the four years since the last elections. Perhaps the new parliament, with some new lawmakers, can re-energize the role the legislative branch plays in the country.