Russia and Kazakhstan may be nominal allies, but their geoeconomic interests are not always aligned. As Astana seeks to develop the Middle Corridor – a transportation link connecting China and Europe through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, bypassing Russia – Moscow reportedly aims to build a trade and logistics route that would connect Russia and Kyrgyzstan, thereby circumventing Kazakhstan.

While various regional actors and international institutions actively invest in the Middle Corridor, also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transportation Route (TITR), a potential route linking Russia and Kyrgyzstan, through Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, remains merely an idea. From the geopolitical perspective, the TITR is seen as an alternative to reach European and international markets and bypass Russia. But what is the primary goal of the Russia-Kyrgyzstan route?

Although both Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are members of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, queues of trucks at the Kyrgyz-Kazakh state border seem to have become a norm. Bishkek accuses Kazakhstan of “artificially creating obstacles at the border to weaken competition from Kyrgyzstan”, while the Kazakh authorities claim that Kyrgyz truckers are “unwilling to comply with Astana’s requirements and submit fraudulent documents for cargo.”

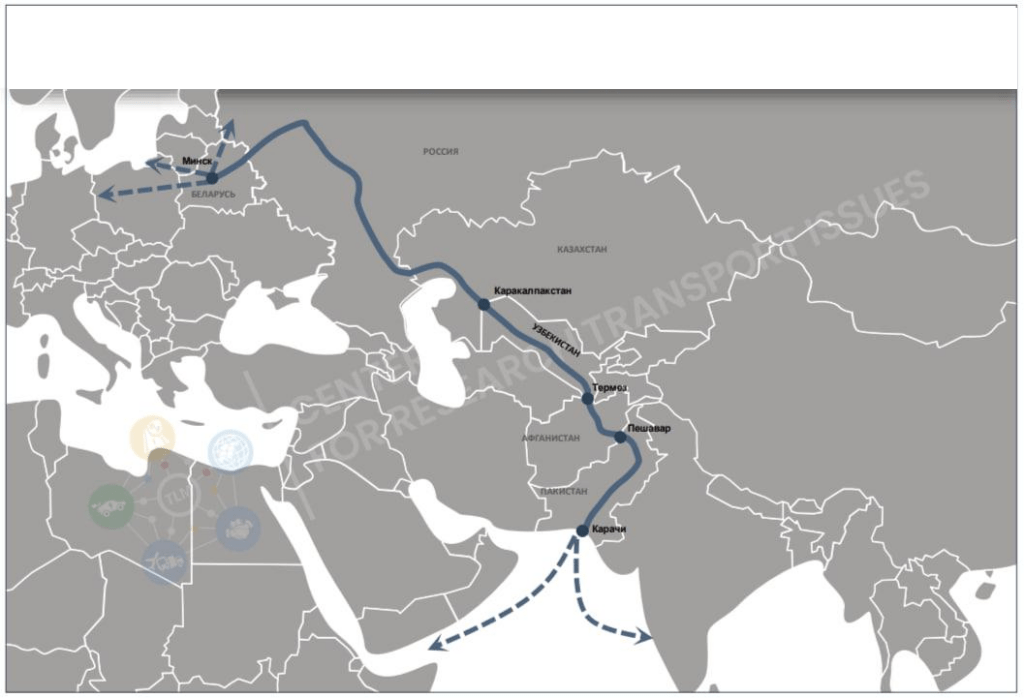

Since Kyrgyzstan’s main connection with Russia – the major market for its agricultural products – goes through Kazakhstan, it is Astana that has the upper hand over Bishkek. From a purely economic perspective, a new route, including sea transport across the Caspian Sea, would enable faster delivery of vegetables, fruits, as well as other goods from Kyrgyzstan to Russia. However, it remains highly uncertain if Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, as transit countries, are genuinely interested in this project.

“Both nations are far more interested in East-West trade, actual supply chain relocations into the region, and new gas contracts with the West,” Samuel Doveri Vesterbye, Managing Director of the European Neighborhood Council, told The Times of Central Asia.

In his view, a Kyrgyzstan-Russia corridor would offer a limited amount of trade, due to the sanctions the West imposed on Moscow over its actions in Ukraine. But in spite of that, Kyrgyzstan, like all countries, tries to be part of any connectivity corridor.

“There is a lot of ‘corridor competition’ at the moment. Most of it is bluff. It is important to look at which projects are being built and how much investments is going into them. The Russia-Kyrgyzstan corridor, at present, is more hot air than reality. There is no funding from the United States, the European Union, China or Turkey. Also, major players like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) do not seem interested in funding the construction of this route. Therefore, its lifespan and potential look rather limited,” Vesterbye stressed.

European institutions seem interested in further development of the Trans-Caspian International Transportation Route. From the European Union’s perspective, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased the need to find alternative, reliable, safe and efficient trade routes between Europe and Asia. That is why Brussels is reportedly willing to invest €10 billion ($10.5 billion) into the Middle Corridor.

For Moscow, on the other hand, a transport corridor through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan serves as a strategic tool. According to Rahimbek Abdrahmanov, a senior economist at the Center for Political and Economic Research, this project is particularly important given the changing geopolitical situation and the potential risks of disruptions in transportation through Kazakhstan.

“It undermines Kazakhstan’s economic position, which has significantly strengthened in recent years, partly due to the redirection of logistics flows through its territory following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine,” Abdrahmanov told The Times of Central Asia, emphasizing that weakening the largest Central Asian country aligns with Russia’s traditional approach of preventing the economic and military-political empowerment of countries within its sphere of influence.

As he sees it, Russia has historically always sought to limit the economic and political independence of countries it considers part of its geopolitical orbit. That is why Astana likely views Moscow’s plans to construct a bypass corridor with caution and concern.

“As the largest country in the region and a key transit hub, Kazakhstan traditionally plays an important role in regional trade. A new corridor bypassing its territory could reduce Kazakhstan’s influence as the main transit route for goods moving between Russia, Central Asia, and China,” Abdrahmanov stressed, pointing out that the bypass route could also mean reduced transit revenues for Astana and a diminished role in regional economic processes.

For Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand, the new route means reducing its dependency on Kazakhstan and strengthening its economic ties with Russia and other partners in Central Asia. For Uzbekistan, according to Abdrahmanov, the new link can help Tashkent achieve its goals of improving transport infrastructure, gaining access to international markets, and strengthening trade ties with Russia. In his view, Turkmenistan, despite its policy of permanent neutrality, is unlikely to obstruct the project.

“As a result, the new route could strengthen Russia’s ties with Central Asia and align with its strategy of diversifying transport flows under the pressure of Western sanctions. The regional actors, maintaining neutrality on this issue, remain important partners for Moscow,” Abdrahmanov concluded.

Although the corridor has the potential to become a vital trade and logistics route linking Central Asia and Europe through Russia, as long as relations between Moscow and the West remain in a ‘new Cold War mode’ the Middle Corridor is likely to remain the most viable option for Central Asian nations to increase their international significance and attract investment.