BISHKEK (TCA) — For Central Asia, China’s Belt and Road Initiative is an opportunity to transform from a landlocked to a transit region, and thus receive a new impulse for its economic development. We are republishing this article on the issue, written by Avinoam Idan*, originally published by the CACI Analyst:

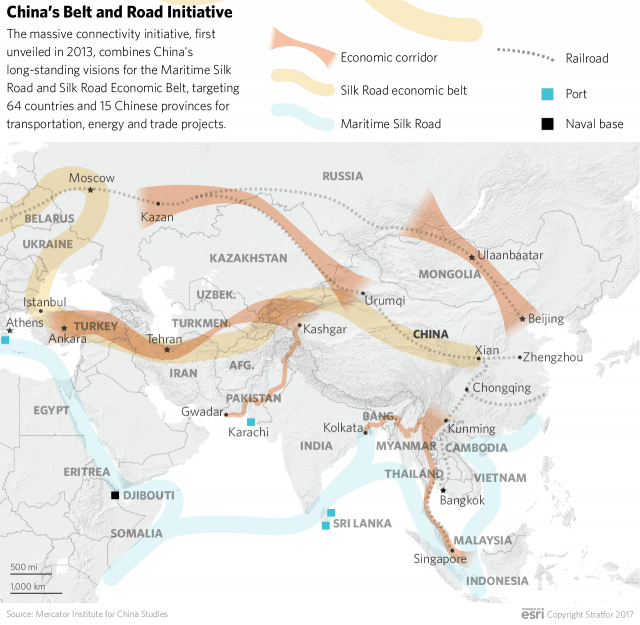

One of the most significant factors impacting Central Asia is its landlocked geography. This situation affects almost every sphere of life—foreign policy, national security and economy. However, China’s BRI project may alter the impact of China on the region. China’s BRI can transform Central Asia from its landlocked state to a transit region between Asia and Europe. Essentially, China is unlocking landlocked Central Asia. Recently, there have been two significant developments: the increase in volume of freight passing through the “dry port” of Khorgos, (in Kazakhstan), and the acceleration of the implementation of the China-Pakistan corridor leading to the Indian Ocean. Each of these developments plays a part in the Chinese initiative and in its impact on Central Asia. The BRI is, thus, the trigger for the geopolitical earthquake in the region.

BACKGROUND: The major geographic characteristic of the Central Asian countries established following the break-up of the Soviet Union is the fact that they are landlocked. This factor creates challenges in all spheres of development – foreign policy, security, and unique human development. Thus, the average GDP of these landlocked countries reaches only 57 percent of that of their maritime neighbors. The cost of shipping reaches 10 percent above that of maritime countries. The combination of geographic location, trade and economic growth explains the cost of being landlocked. Among the results is the fact that these countries suffer from a thirty percent handicap in comparison with their maritime competitors. Therefore, landlocked nations must receive ongoing assistance from international institutions, such as the World Bank and the IMF. They are perceived as countries with high import rates and low export revenues. According to the UN Human Development Index, most of such countries are at the bottom of the list.

From the beginning of their independence, the leaders of the new states of Central Asia recognized and articulated the limitations of their landlocked geography and sought increased transportation and connectivity as a means to deal with this handicap. Kazakhstani President Nazarbayev stated at that time that the lack of access to the sea could be detrimental to the country’s economic development, and to its political independence, as well as making participation in international economic relations difficult.

President Karimov of Uzbekistan expressed similar sentiments, emphasizing the need to continue to seek new solutions to these problems, with an effective transportation system and secure access to the sea.

For the first two decades of independence, there was considerable activity in rebuilding infrastructure and piecemeal efforts to connect Central Asia to the rest of the world. But much of this remained on the conceptual level. The European Union’s Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA) program was the first to envision the region as a transport corridor between east and west. But while it generated numerous smaller concrete projects, it did not have the magnitude to undo the effects of landlockedness.

The conflict in Afghanistan also impeded the attempts of Central Asian states to reach the Indian ocean, geographically the closest warm water ports for the region. While there have been continuous hope for a resolution to the conflict that would enable transit trade through Afghanistan, these hopes have yet to be realized. The U.S.-launched New Silk Road strategy, announced in 2011, offered to remedy this situation, but it never gained significant momentum. It suffered from a lack of top-level support in the U.S. government, and from the fact that it was originally an exclusively north-south affair, failing to include the Caucasus.

Against this background, some of the main advances have been made unilaterally by regional states. Leading among these is the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad, built by Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. (See December 7, 2017 CACI Analyst) But while these were separate affairs, a large-scale vision for transportation infrastructure that would relieve Central Asia’s landlocked nature did not arise until Beijing formalized its earlier disparate initiatives into the Silk Road Economic Belt, which subsequently came to be encompassed within the BRI.

Understanding this reality helps to explain why the states of the region have embraced China’s BRI and do not see it as threatening. The BRI integrates the countries of Central Asia with a new and multi-faceted transportation network, as well as connecting Central Asia to far-away countries and markets.

IMPLICATIONS: The BRI, according to Chinese estimates, will encompass approximately sixty-five countries, 4.4 billion people and will improve connectivity over an area that produces approximately 55 per cent of the global GDP and includes close to 70 per cent of the population of the world. According to the BRI scheme, Central Asia becomes the main continental gateway for Chinese transportation routes westward. As such, an area that was isolated, cut-off and landlocked turns into a transit region of great importance to China as well as to other nations in the area.

There are several geopolitical trends resulting from this change in the region: The first is the intensification of the win-win basis of the relations between the Central Asian countries and China: BRI is currently China’s main policy vector. It now will need to deepen ties with the states of Central Asia, and, while Chinese influence will grow in Central Asia, the reverse works as well, and China’s dependence on good ties and cooperation with the region will grow.

Second, the importance of the Central Asian countries is rising. Central Asia will be more integrated with China’s Western provinces and significantly contribute to the development of this part of China. This can lead to greater two-way influence between these regions, with potential political implications. In addition, China is even more invested than before in the stability of Central Asia, which will become a precondition to the success of the BRI.

Third, there is likely to be an intensification of Chinese security involvement in Central Asia. Chinese security and, potentially, even military involvement in the region may grow, as has been seen in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.(See April 12, 2018 CACI Analyst) Since Central Asia is key to the success of the BRI, its security challenges, mainly current threats from violent extremist Islamist groups, can be expected to lead to an increased Chinese security presence, and perhaps even to active military involvement in the area. The building of the first Chinese military base outside of China, in Djibouti on the Red Sea, is the first sign of a trend that can be expected to characterize Chinese conduct in critical places such as Central Asia. China’s economic and political influence may not be enough to ensure stability in the area, however Chinese current activity, both in Afghanistan and in the area of Tajikistan, is an indication of these security trends.

Fourth, the importance of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization will increase in the new developments in Central Asia: The Shanghai Organization (SCO), in which both China and Russia are leading participants, is an effective platform, both for the new pattern of activity for China in Central Asia and for a coordinated framework for Russian-Chinese cooperation in the area. The recent inclusion of India and Pakistan reflects the growing influence of the BRI on the focus and activity of the organization, including potential access of China and the Central Asian region to the Indian Ocean, through the port of Gwadar in Pakistan.

Fifth, an important issue to be watched is how China’s growing presence affects Russian-Chinese relations in Central Asia and in general. The two countries claim to have an excellent relationship, and are aligned on many international issues. Both also have an interest in the stability of Central Asia. But it is also clear that their interests differ, in that Russia sees Central Asia as part of its sphere of influence. Moscow was willing to accept a situation where Beijing gained influence in the economic realm, while Moscow continued to dominate the region’s security. When, as appears certain, China’s interests require a stronger direct involvement in the region’s security affairs, it remains unclear how Moscow will react to this.

Some liabilities of the BRI initiative should be noted. First, India is highly skeptical of the BRI, which it views as a way to exclude India from the region. Since relieving Central Asia’s landlocked nature will also require gaining access to South Asia, it is imperative that steps are taken to complement the China-Europe connection with one connecting to South Asia. Second, Central Asian states are well aware of the problematic experiences of some countries with Chinese investments – the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka being the most notable example – and of the fact that Chinese investments rarely generate employment opportunities for the local population, as construction is normally done by Chinese workers. Third, Chinese investments in hard infrastructure will need to be followed by the creation of the soft infrastructure needed for trade – from logistics to insurance and warehousing, matters where Central Asian states will seek to ensure they are not bypassed by outside actors. Overall, however, the prospect of escaping some of the consequences of being landlocked more than make up for these potential downsides.

CONCLUSIONS: Central Asia is going through a geopolitical upheaval. President Xi Jinping’s BRI, declared in 2013, is about to change the geopolitical reality of this landlocked region.

There is no changing the geographic location; however, geopolitics can often be dynamic. Connectivity is a factor able to change the geopolitical reality in a region whose geographic location is naturally constant. The BRI stands to change Central Asia from a landlocked to a transit region and thus to create a new direction in its development. Success of the BRI and meeting the complex challenges it presents, as well as the level of its implementation will determine the degree to which this initiative will affect the geopolitical dynamics of Central Asia.

* Dr. Avinoam Idan is a geostrategist and a non-resident Senior Fellow with the Washington based Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program. He is based in Israel. Prior to his academic career, he served in the Israeli Embassy in Moscow during the break-up of the Soviet Union.