Afghanistan has increasingly been regarded in expert and journalistic circles as part of Central Asia, which is justifiable from a physical-geographical perspective. However, given current regional realities, it is still premature to classify the country as part of Central Asia in terms of being internationally recognized as such.

The outcome of the 19th-century rivalry between the British and Russian Empires for influence in Central Asia, known as the “Great Game,” not only established the modern southern borders of the region but also set Afghanistan and its northern neighbors on entirely different social and historical paths. The countries differ in value systems, ideologies, public consciousness, and, of course, economic development.

At the same time, experts from the Russian Institute for Central Asian Studies note that “In the early 21st century, approaches to analyzing regional realities shifted towards geo-economics. The spatial dimension of Central Asia began to be seen as a zone for pipeline transit.”

This perspective is hard to argue against — Afghanistan’s current geopolitical interests and challenges are largely tied to the economic interests of countries at the regional level. This includes India, Iran, China, the UAE, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, and the Central Asian states, for whom Afghanistan’s prospects are evident. Chiefly, these prospects concern its transit potential as a territory connecting various parts of Asia. Four out of the six logistics corridors under the Asian Development Bank’s Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program (CAREC) pass through Afghanistan into Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Other relevant projects include the “China–Pakistan Economic Corridor” under the “One Belt One Road” initiative, the “Trans-Afghan Corridor,” and the TAPI Gas Pipeline.

However, Afghanistan’s current situation, particularly given the stagnant Afghan-Pakistani conflict, casts doubt on the feasibility of these and other major projects involving Afghanistan. As previously stated by TCA, the future of these large-scale projects involving Central Asian countries, as well as regional stability, a fundamental condition for steady economic development, depends directly on whether an understanding is reached between these two nations.

Thus, a geo-economic approach to redefining Central Asia’s new boundaries still requires a different reality.

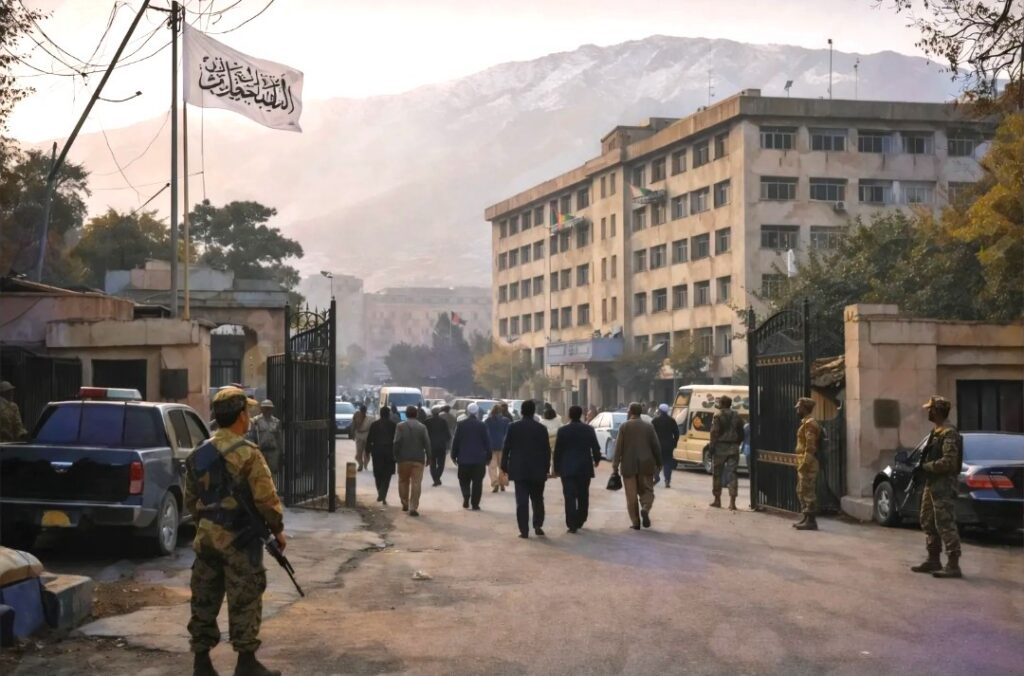

Meanwhile, within Central Asia itself, there is little enthusiasm for political rapprochement with Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. The primary focus is on trade/economic and humanitarian cooperation, with no broader agenda, particularly at a regional level. Tajikistan’s position is significant here, as its authorities continue to view the Taliban as a threat and tread cautiously in building relations with them.

What Prevents Central Asian Countries from Accelerating Relations with Afghanistan?

The answers lie not only in different developmental trajectories and scenarios. First and foremost, Afghanistan is still associated with “uncertainty” and numerous risks, particularly in terms of security.

According to many assessments, the Afghan-Pakistani zone will, in the long term, remain a source of terrorist and religious-extremist threats to Central Asia. These conclusions are based on a retrospective analysis of escalating tensions, current processes in Afghanistan, and the geopolitical confrontation of global powers in the area.

For example, the Soviet invasion in 1979 fostered the consolidation of the Afghan mujahideen, united for the first time since the Anglo-Afghan wars, through political, financial, and military support from NATO countries, China, and Islamic states. The 1979–1989 intervention led to the emergence of an international Islamist movement, which attracted thousands of foreign militants, primarily from Muslim countries, to the Afghan-Pakistani zone. This war gave rise to the term “Afghan Arabs,” referring to those from the Arab world who joined the mujahideen.

In his book, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia, Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid notes that around 35,000 Muslim radicals from 43 Islamic countries in the Middle East, North and East Africa, Central Asia, and the Far East fought alongside the Afghan mujahideen. Financed by the Pakistani government, tens of thousands more foreign Muslim radicals came to study in hundreds of new madrasas in Pakistan and along the Afghan border. Ultimately, over 100,000 Muslim radicals were influenced by jihadist ideologies.

Among them was the then-unknown Osama bin Laden, who arrived in Afghanistan to participate in the jihad against the Soviet Union — an experience that enabled him to establish al-Qaeda in 1991 for a global war against the Western world. Another notable “Afghan Arab,” Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, later founded the terrorist group Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, which eventually evolved into the Islamic State.

For jihadists worldwide, the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan symbolized the triumph of Islam over a communist power that had invaded a Muslim country. Furthermore, they gained confidence in the necessity and feasibility of spreading their jihad to other nations.

Thus, the Soviet-Afghan war set a new “trend” in global terrorism, with al-Qaeda as one of its products. Following the Soviet withdrawal, the “terrorist center” shifted toward the Middle East and later the African continent. However, many experts believe that, given the growing geopolitical confrontation around Central Asia and ongoing shifts in spheres of influence, Afghanistan will remain a focal point for major players due to its explosive potential.

Taliban Governance: Current and Long-term Questions

Today’s Taliban have no ambitions to export their revolutionary ideas abroad. Their primary concerns are international recognition and stabilizing the country’s socio-economic situation. Resolving territorial disputes with Pakistan is also pressing. But what will happen in the long term, once the regime strengthens? What will its character be, given the Taliban’s current radical and uncompromising stance on several issues significant to the international community?

Such concerns, among others, are particularly pressing for Central Asian nations. While Pakistan and Iran have historically been deeply involved in the “Afghan knot,” as TCA has previously pointed out, Iran and Pakistan are historically most similar to Afghanistan in terms of their understanding of ethnic, economic, and political conflicts and border issues. This is not the case with the Central Asian republics, which are just getting to know their southern neighbor.

What Worries Central Asia?

First, the Taliban continues to allow terrorist and extremist groups with a Central Asian orientation to establish themselves in Afghanistan. These include Jamaat Ansarullah, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM, also known as the Turkistan Islamic Party), which make no secret of their goal of overthrowing secular regimes in Central Asia.

According to many governments and experts, these terrorist groups continue to be present in Afghanistan. In particular, a UN report from July 2024, notes that despite lacking the capacity to conduct large-scale operations abroad, al-Qaeda is seeking to increase cooperation with regional terrorist organizations of non-Afghan origin.

UN experts believe that while the Taliban have significantly limited the activities of al-Qaeda’s core and affiliated groups in the country, there have been visits to Afghanistan by prominent al-Qaeda figures, particularly related to training. Ongoing reorganization and training, in the view of the specialists, are indicative of the group’s long-term intentions. The same report notes that “Member States express continued concern that terrorism emanating from Afghanistan will, in most scenarios, contribute to insecurity in the region and beyond”.

The Taliban acknowledge the presence of militants from Central Asian terrorist organizations on their territory but claim there is no threat from them. They believe they can integrate foreign fighters into Afghan society and make Afghanistan a second home for them. At the same time, the Taliban will allegedly ask those who do not want to integrate to leave Afghanistan – which begs the question: where will this category of terrorists go?

This position of the Taliban looks somewhat idealistic, even utopian – all Central Asian countries have faced the challenges of deradicalizing and integrating their citizens who took part in the activities of international terrorist organizations, primarily in Syria. In general, this experience cannot be called successful. This, in particular, is stated in a special study, “Radicalization and deradicalization: studying the experience of foreign terrorist fighters”, conducted by the Research Center for Religious Studies and the International Center of Excellence for Combating Violent Extremism “Hedayah”. In it, using Kyrgyzstan as an example, experts describe in detail all the complexities of these processes.

In this regard, doubts about the possibility of deradicalization (as understood by Central Asian countries) are quite reasonable.

Secondly, modern Central Asia continues to face the challenges of Islamic radicalism, and religious fundamentalism itself has become a global problem.

Some experts and observers tend to conclude that radical Islamism does not pose an existential threat to regional stability for Central Asian countries. According to this view, the majority of people in the region are moderate Muslims who are more concerned with the practical aspects of creating a better life for themselves and their communities than with zealous adherence to religious ideals. However, Syria, too, was once a country with moderate Islam, and neighboring Lebanon was called the “Switzerland of the Middle East.” Now, the war in Syria has led to a humanitarian crisis of serious proportions.

In this regard, neighboring Afghanistan with its form of fundamentalist Islam could possibly play a role in the Islamization of the entire region.

Here, it will be appropriate to return to the Soviet-Afghan war. In particular, after 1979, with substantial foreign assistance, many madrassas and religious training centers, most of which still exist today, were established in the tribal zone of Pakistan and certain areas of Afghanistan, along with special training bases for militants. This was a feature of that conflict and created the conditions for the emergence of a phenomenon in which the ideological direction of Islam began to take on a militant, jihadist character.

According to various data, most Afghan refugees, whose total number in Pakistan during the entire period of the civil war (1979-2021) is estimated at 6-7 million people, were and are being trained in them. It was these graduates who became the basis for the formation of the Taliban movement, as confirmed by Taliban functionaries themselves.

Thus, the Soviet Union contributed to the strengthening of radical and militant Islam in the Afghan-Pakistani zone, while the Pakistani authorities have so far failed to establish control over the Pashtun tribal zone.

After August 2021, the relevance of madrassas in the Pakistani tribal zone continues in light of the stagnant conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan, which is based on territorial claims and Pashtun nationalist ambitions.

At the same time, the Taliban, having gained power in the country and considerable experience in the religious training of the population, have begun to actively implement their emir’s message to open religious schools (madrassas) and mosques throughout the country. Many general education schools, especially in the provinces, are being transformed into madrasas with the opening of mosques attached to them. Emphasis is being placed on expanding the network of madrasas in the northern parts of the country, especially in the northeast, where inter-ethnic tensions are particularly strong. In this regard, these moves by the Taliban are seen as measures to strengthen their regime in the troubled regions and to Pashtunize the local population.

The Taliban have not limited themselves to expanding the network of religious schools – the “jihad madrassas” have become an innovation.

According to the Persian-language version of The Independent, the establishment of jihadi madrassas was first proposed in early 2022 on the orders of Akhundzada. According to the plans announced by the Taliban, a large jihadi school will be built in each provincial center and three schools in each district. In total, the publication points out, the Taliban regime is establishing 1,224 schools, including 34 large jihadi schools in cities, to promote jihadi ideology and strengthen its social base. A writer for The Independent called these madrassas a “time bomb for neighboring countries,” and the Afghan publication Jomhor called them a nightmare for the future of the region.

The BBC quotes an Afghan expert as saying that “one of their goals is the military use of students from these schools in possible future wars. The fact is that the creation of such schools gives the Taliban a purely ideological reserve force that will never face a shortage of fighters in future wars.”

Australian professor William Maley, the author of several books on Afghanistan, draws similar conclusions. In his view, one of the greatest dangers is the Taliban’s desire to raise a new generation socialized to the Taliban’s extremist mindset.

For the sake of objectivity, it should be noted that in neighboring Islamic Iran, expert circles have also expressed concern about jihadist madrassas. Thus, the Tahlilroz publication, citing the opinion of the theological specialized forum Taqrib News Agency, points out that the intellectual roots of the Taliban originate in the Deobandi school, according to the teachings of which a Muslim must be committed to three conditions:

- The Muslim is loyal to the religion and the country of which he is a citizen or resident.

- The boundaries of the Islamic Ummah take precedence over national boundaries.

- The obligation and duty to wage jihad anywhere in the world to protect Muslims.

The Iranian expert in his study does not rule out that the Taliban will use these interpretations in establishing their religious schools, and given that deviant and extremist currents are active among the Taliban, the establishment of such schools will educate Takfiris (those hostile to Muslims deemed heretical) more than training religious scholars. This would not only lead to a crisis in Afghanistan, but would be dangerous for the region and the entire world.

In Afghanistan, a separate body, the General Directorate of Jihadi Schools, has been created for the purpose of “jihadi madrassas”. Its head is Sheikh Abdul Wahid Tariq.

These estimates and the number of jihadi madrassas are alarming in themselves, especially against the background of the Taliban’s strict measures to regulate the social life of Afghans, primarily in gender policy.

A popular forecast in expert and journalistic circles now is that if Syria manages to achieve relative stability, which is very likely, foreign fighters, mainly from Central Asia, are likely to move to Afghanistan. Given the current situation in that country, this forecast looks quite reasonable.

Thus, Afghanistan has been and remains convenient for the birth of all sorts of narratives in the context of threats to the region and the world.

At the same time, the Taliban themselves have so far been unable to counter anything except to claim that their regime poses no threat to anyone. Clearly, they need more transparency and openness, as well as an objective understanding of the views and concerns of their neighbors, whose distinction between the definitions of “ideology” and “religion” is not only linguistic.

The countries of Central Asia themselves are inclined not to actualize the problems and challenges described above; they have chosen the path of dialogue and gradual integration of Afghanistan through economic ties, which should bring this country towards being an understandable and adequate member of the region.

According to The International Crisis Group, dysfunction in the relationships between Afghanistan and its neighbors affects the lives and livelihoods of people across South and Central Asia. Kabul and its regional partners should explore ways of expanding trade, managing disputes over water and other shared resources, and combating transnational militancy. Failure to do so could lead to instability across a vast area.