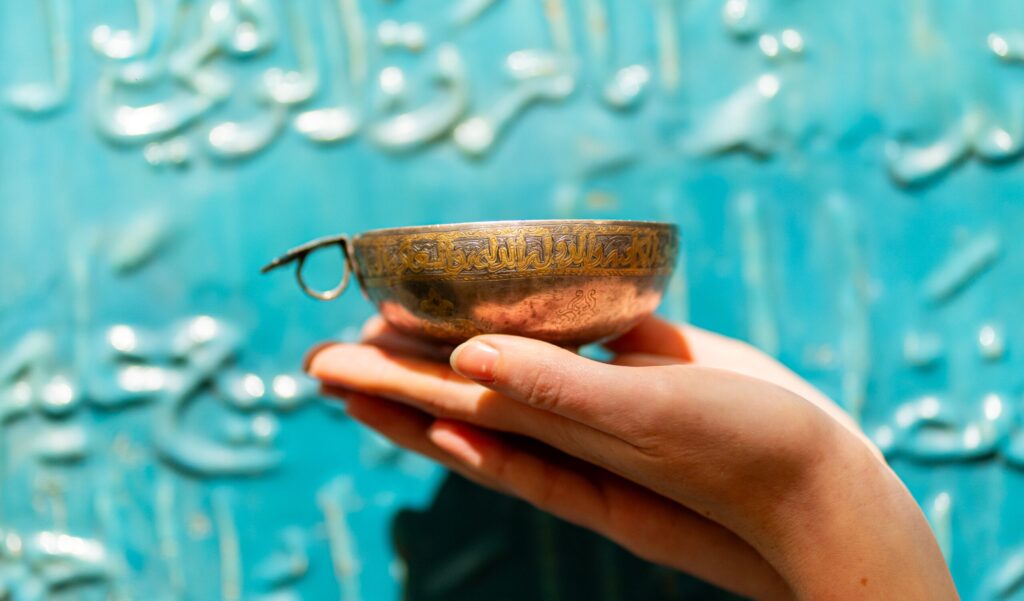

On October 29, Sotheby’s will host its Arts of the Islamic World and India sale, featuring a dazzling selection of manuscripts, ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry that together trace the creative reach of Central Asia across six centuries. The auction highlights how the region’s artists shaped Islamic visual culture from the early medieval period to the Timurid age. Among the most important works is a rare page from the monumental Baysunghur Qur’an, produced around 1400 in Herat or Samarkand. Another piece connects to the earlier Samanid Dynasty, whose rule from Bukhara and Tashkent fostered a flourishing of calligraphic pottery in the ninth and tenth centuries. The Arab geographer al-Maqdisi once praised the “large bowls from Shash,” an early name for Tashkent, noting their reputation throughout the Islamic world. [caption id="attachment_38298" align="aligncenter" width="1797"] A line from the 'Baysunghur Qur'an', attributed to 'Umar al-Aqta, Herat or Samarkand, circa 1400; image: Sotheby's[/caption] Two colorful Timurid mosaic tiles from the fourteenth or fifteenth century illustrate the architectural splendor of Samarkand and Herat. Their glazed patterns in cobalt, turquoise, and white once formed part of vast decorative panels in mosques and mausoleums. The geometric interlace and stylized foliage that define them became a visual signature of Timurid architecture, a style that spread from Central Asia to Persia and India. [caption id="attachment_38301" align="aligncenter" width="1346"] A Golden Horde turquoise and pearl-set gold belt or necklace, Pontic-Caspian Steppe, 14th century; image: Sotheby's[/caption] The Times of Central Asia spoke with Frankie Keyworth, a specialist in Islamic and Indian Art at Sotheby’s, for a closer look. TCA: How did manuscripts like the Baysunghur Qur’an serve as symbols of power and faith in the Timurid court, and what does its immense scale - a Qur’an so vast it took two people to turn a page - reveal about the empire’s ambition, artistry, and self-image? Keyworth: The manuscript was a hugely ambitious and challenging project, even just by the tools it would take to create, with monumental sheets of paper measuring 177 by 101cm., and a large pen whose nib would have to measure over 1cm. Displayed on a magnificent marble stand, the manuscript would be a staggering visual representation of the patron’s wealth and piety. Their subsequent use during public recitation reinforced the elite’s religious aspirations. The fact that this manuscript is unsurpassed by any other medieval Qur’an and remains so valued centuries after it was produced at the turn of the 15th century reveals the key role manuscripts played in the establishment of the Timurid dynastic image. [caption id="attachment_38299" align="aligncenter" width="1346"] A Timurid brass jug (mashrabe), Herat, Afghanistan, 15th-early 16th century; image: Sotheby's[/caption] TCA: A brass jug from Herat shaped like a Chinese vase, a ceramic bowl from Tashkent inscribed in Arabic script - these objects tell of traders, scholars, and artists linking worlds from Samarkand to Beijing long before globalization had a name. What can you tell us about how this trade transpired, and are there similarities to modern transport corridors? Keyworth: Trade via the so-called Silk Road endured for...