Michael Hilliard is Director of Defense & Security Analysis at the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, where he leads a specialist project analyzing the armed forces of Central Asia. The Oxus Society’s latest report, focusing on Uzbekistan’s military, has just been released.

The Times of Central Asia spoke with Hilliard about the report, Uzbekistan’s evolving defense doctrine, and its future role as a military power in the region.

TCA: In light of the new report on Uzbekistan’s military, how would you characterize Uzbekistan’s overarching security and defense doctrine, especially in relation to the broader Central Asian region?

Michael Hilliard: Uzbekistan’s primary defense doctrine is essentially internally focused.

Since independence, and particularly since the events in Andijan in 2005, Tashkent has concentrated on transforming its forces into a rapid-response military with specializations in counterterrorism, crowd control, and dispersal operations.

When you speak with officers or policymakers within the defense establishment, 2005 is a recurring reference point. During those early hours, protestors overran a motor rifle unit and seized weapons. Many defense personnel still believe that if they had been able to react faster, the final outcome in the square might have been different. This need for rapid adaptability has driven much of Tashkent’s defense policy since then.

TCA: The report notes that Kazakhstan has now overtaken Uzbekistan as the region’s leading military power and that this gap is likely to widen. To what extent does this reflect Tashkent’s greater emphasis on regional cooperation and the resolution of border disputes, rather than competition?

Hilliard: Kazakhstan’s economic dominance makes this outcome unsurprising. The country now accounts for just under 60% of Central Asia’s total GDP as of 2024. With that level of wealth, Astana naturally has greater resources to allocate to defense.

However, Uzbekistan traditionally spends a higher proportion of its budget on the military. Despite having only half of Kazakhstan’s GDP, it has often matched Kazakhstan’s defense spending in real terms.

If Kazakhstan simply accelerates its defense spending to the regional average, it will quickly surge ahead. Ultimately, it’s an issue of economics; Kazakhstan has more money to spend.

TCA: What is the role of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and its Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in shaping Uzbekistan’s regional military posture?

Hilliard: While some once had ambitious visions for the SCO, today it’s primarily intelligence-focused. Joint exercises are still held but remain limited, and RATS’ influence has declined somewhat following China’s controversial maneuvering within the organization.

At present, RATS focuses more on identifying individuals or groups, such as traffickers or terrorist networks, that all member states have a shared interest in apprehending. It’s quite different from the CSTO, where Moscow wields far greater control.

TCA: How might Tashkent view the recent clashes between Taliban and Pakistani forces, given that Pakistan currently chairs RATS?

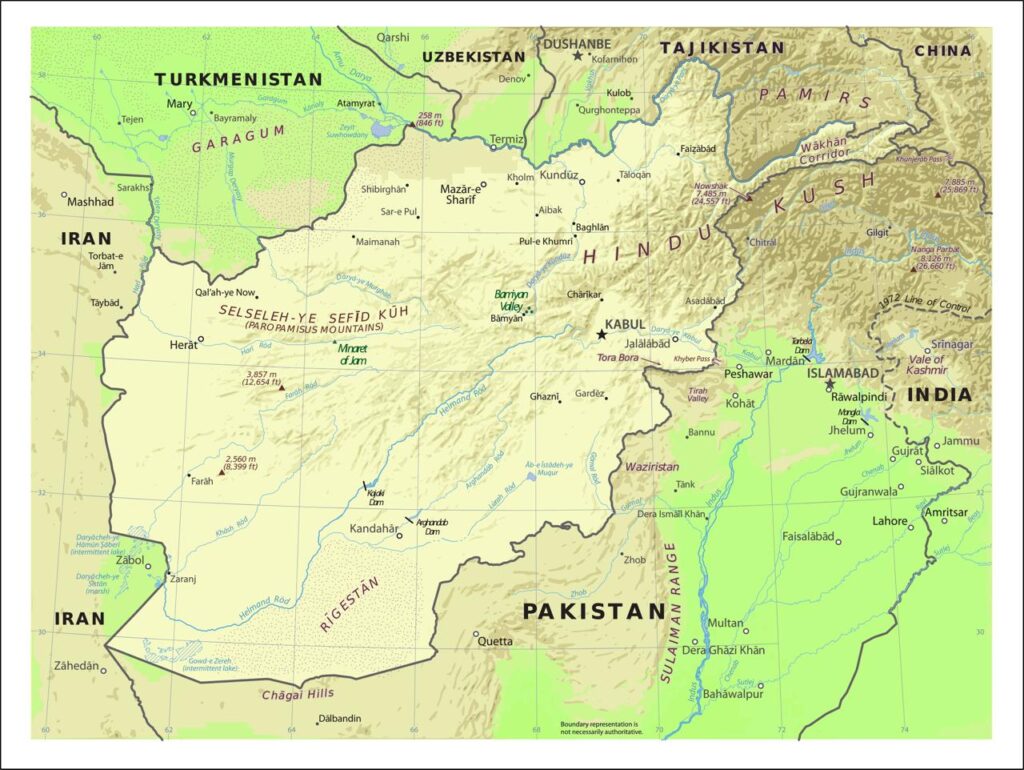

Hilliard: Tashkent’s attention is mainly on northern Afghanistan, not the Taliban-Pakistan clashes in the southeast. These incidents appear limited, so they’re unlikely to alter Tashkent’s calculus significantly. However, they do make cross-regional initiatives such as the Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline even less likely.

Regardless, Uzbekistan remains deeply concerned about overall stability in Afghanistan and the risk of unrest spilling across borders.

TCA: Given Uzbekistan’s focus on preventing instability in Afghanistan from spreading, whether through the IMU, ISKP, or other groups, how capable is its military of meeting such challenges?

Hilliard: Uzbekistan maintains substantial garrisons along the Afghan border, particularly around Termez. The city is heavily fortified, a legacy of Soviet preparations before the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan.

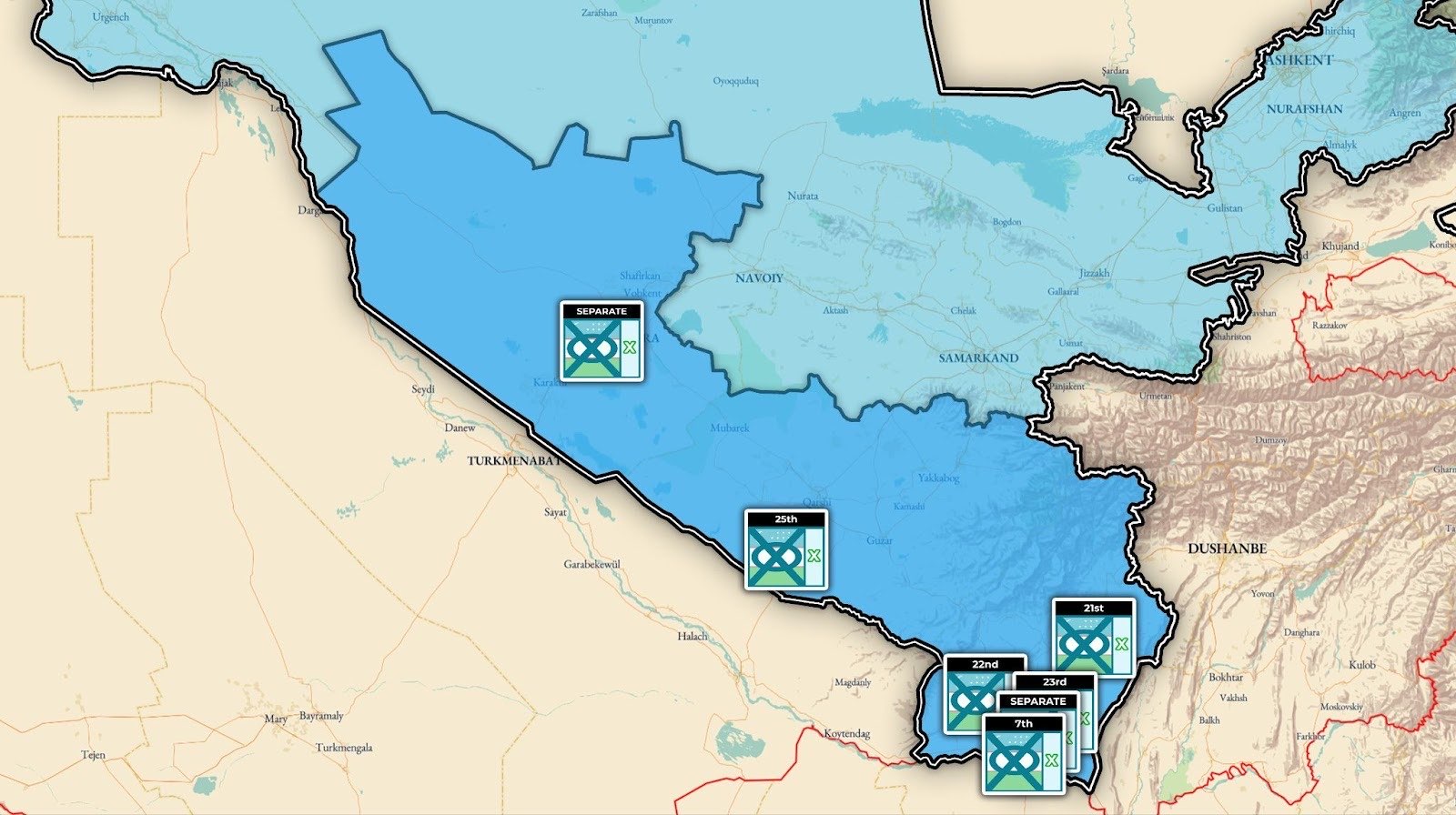

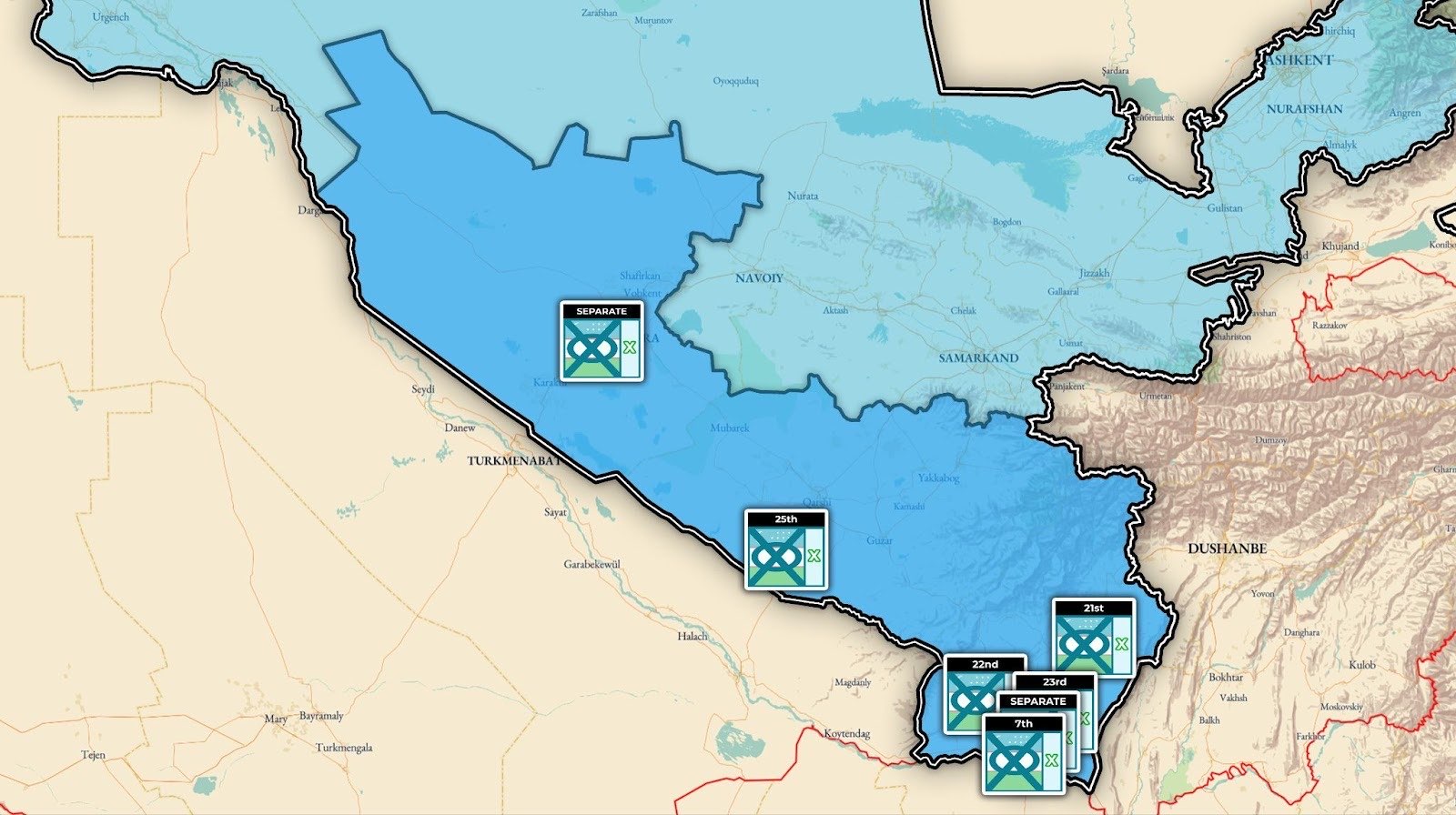

By contrast, many of the country’s best rapid-response units are based in the Fergana Valley. For example, some of the newest drone units, Special Operations Battalions (SOBs), and elite formations like the 17th Air Assault Brigade, one of Uzbekistan’s best-trained and best-equipped units, are stationed in Fergana rather than Termez or Tashkent.

Map of major ground force brigades, under the command of Southwest Special Military District

TCA: To what extent do Uzbekistan’s joint military exercises with the SCO or other regional partners improve interoperability, particularly with Kazakhstan?

Hilliard: That’s an interesting question. Uzbekistan conducts many multilateral exercises and gains value from them.

However, the benefits are somewhat limited. The same personnel often rotate through multiple exercises, reducing the breadth of experience across the force. Moreover, many of these drills resemble what I’d call “pageantry exercises”, highly choreographed events, similar to pre-2022 Russian displays, designed more for optics than for genuine combat readiness.

TCA: How has resolving border disputes with Kyrgyzstan influenced Uzbekistan’s defense posture, especially in the Fergana Valley, which is vital to both its economy and population?

Hilliard: While some disputes have been settled officially, the underlying tensions remain. Border incidents tend to arise in the field, not in headquarters.

Patrols operate in remote areas with broad engagement rules; they can fire on illegal border crossers or insurgents. That means 18-year-olds with minimal training must make split-second life-or-death decisions.

In calm times, patrols from both sides often just wave to one another. But during tense periods, such as before the 2022 Batken clashes, nervousness on either side can cause confrontations to escalate quickly.

Recent demarcation efforts have eased some tensions, but they haven’t eliminated the risk of future flare-ups. What happens on the ground often differs greatly from the official narrative in headquarters.

TCA: How would you assess the strategic depth of the Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan relationship? Are there hidden points of tension behind the public cooperation?

Hilliard: There’s a lot of potential for defense cooperation, especially in industrial and logistical areas, but limited trust.

Both countries use similar equipment and munitions, so pooling repair and maintenance facilities could save time and money. For instance, both currently send their aircraft to Belarus for major overhauls. It would make sense to jointly refurbish facilities like the aircraft plant in Chirchik. But Astana may be reluctant to depend that heavily on a regional peer and potential competitor.

TCA: How prominently does Karakalpakstan figure in Uzbekistan’s internal security planning after the 2022 unrest?

Hilliard: Karakalpakstan remains highly sensitive at all levels of government.

Most of Uzbekistan’s ground force units are stationed in the east, far from Karakalpakstan. While smaller units operate in Urgench and a single Ground Forces brigade is based in Nukus, the majority of personnel in the region belong to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Border Service, or the National Guard, forces specialized in crowd control and disaster response rather than conventional warfare.

Since 2022, training and communications capabilities in the region have improved significantly, and the government has strengthened its ability to redeploy troops rapidly if necessary.

TCA: Given Uzbekistan’s internal focus and close alignment with Kazakhstan, is there any plausible scenario in which Astana might view Tashkent as a threat?

Hilliard: I’d say no. Neither country has built its military with large-scale offensive operations in mind.

At worst, they might envision a short, localized border skirmish. While some mutual distrust remains among planners, the overall level of trust and cooperation has improved markedly over the past decade. Both governments share broadly similar goals for regional stability.

TCA: How does Tashkent view its long-term dependency on Russia for defense manufacturing and munitions? Can it realistically change that?

Hilliard: Uzbekistan remains deeply embedded in the Russian defense ecosystem because most of its arsenal is Russian or ex-Soviet.

It’s a bit like the “Apple vs. Android” dilemma: switching platforms would require enormous capital outlays to retrain personnel and replace maintenance systems. For an Uzbek general managing a limited budget, upgrading a Russian tank for 5% of the cost of buying a new U.S.-made Abrams makes practical sense.

Russian equipment is also cheaper now due to the weaker ruble, and Moscow often sells to Tashkent at near cost, sometimes even bartering raw materials for weapons. Russia also allows installment payments, which the U.S. would not.

That said, when it comes to new systems rather than upgrades, especially drones, Tashkent looks elsewhere. Russia lags far behind suppliers like Turkey and China in drone technology, and Uzbekistan prioritizes partnerships with those states for modern platforms.

TCA: Is the recent joint venture with a Russian company to build drones in Uzbekistan an example of dependency or capacity building?

Hilliard: It’s part of building domestic capacity. Uzbekistan is investing heavily in drones, which makes sense given the technology’s strategic importance.

While it’s working with Russian firms, it’s also developing joint ventures with Turkey for military drones and with Iran for agricultural drones, where Tehran has relevant expertise. For Tashkent, this is about cultivating an industry rather than deepening dependency.

TCA: Thank you, Michael, for such an interesting in-depth discussion of Uzbekistan’s armed forces and the broader Central Asian security landscape.

Readers of The Times of Central Asia can access the full report as well as the Oxus Society’s Central Asian Military Units Map at the Oxus Society’s website.