The hype surrounding the recent summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Council of Heads of State in Astana has died down, and the expert community has offered differing takeaways, with some experts optimistic and others cautious. Few, however, have considered what new this summit delivered on Afghanistan. In general, what is the role of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in resolving the political issues around long-suffering Afghanistan and rebuilding its economy?

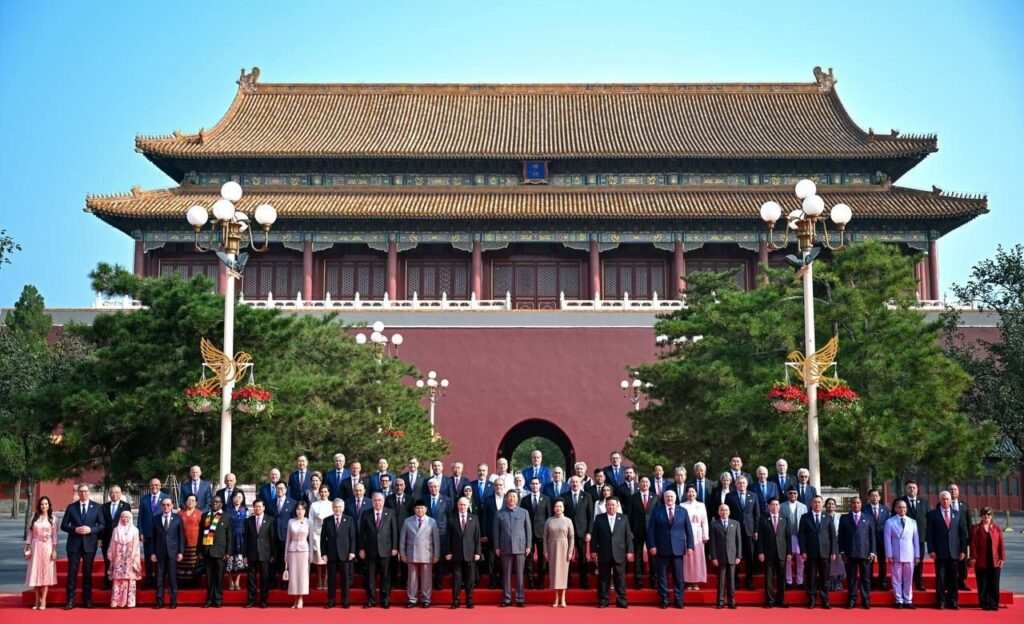

Despite the SCO’s previous hands-off approach to Afghan affairs, the issue of Taliban-ruled Afghanistan was raised for the first time at the highest level of the SCO in Astana, which gives hope that the organization will expand its role. In their remarks, almost every SCO head of state touched on Afghanistan in essentially the same vein, stating the need for peace, stability and security, while underlining the fact that Afghanistan is an integral part of Central Asia.

Indeed, Afghanistan was mentioned in the final declaration of the Astana summit, with Member States “reaffirming their commitment to asserting Afghanistan as an independent, neutral and peaceful state free from terrorism, war, and narcotic drugs [and voicing] their readiness to support the international community’s efforts to facilitate peace and development in that country.” At the same time, there was a clear message to the Taliban that “the establishment of an inclusive government involving multiple representatives of all ethnic and political groups of Afghan society is the only way toward attaining lasting peace and stability in that country.”

These statements represent a rather big step, considering that previously the SCO failed to find a consensus on Afghanistan and develop its own mechanisms to interact with Kabul. The creation of the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group back in 2005 was rather a spontaneous reaction to the US-led coalition’s Operation Enduring Freedom in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack. The SCO itself says the contact group was created because of the “concerns of the SCO countries about the negative development of the situation in Afghanistan and the intention of the SCO to establish a specific consultative dialogue with Kabul.” While the contact group included the members’ permanent representatives to the SCO, only a few events were ever held.

Indeed, interest in the contact group was only really apparent from the Afghan side, which was looking for SCO assistance in rebuilding the Afghan economy and SCO participation in implementing various energy and transport infrastructure projects and creating favorable conditions for Afghan goods to access the markets of SCO countries. However, none of this was realized. The SCO states preferred, as they still do, to conduct relations with Afghanistan bilaterally, and did not support the efforts of the SCO Secretariat to intensify the work of the contact group. In 2010, Uzbekistan directly indicated its interest in building relations with Afghanistan exclusively on a bilateral basis and stated that it would no longer take part in the contact group.

In June 2012, Afghanistan’s application for SCO observer status was granted. Yet this step was more symbolic and failed to jump-start the development of SCO-Afghanistan relations. In July 2021, a month before the fall of the republican regime in Kabul, a contact group meeting took place in Dushanbe between the foreign ministers of the SCO states and their Afghan counterparts, with a joint statement being adopted.

The contact group continues to exist on paper, but uncertainty about its status prevails, as demonstrated at the Astana summit: Russian President Vladimir Putin and Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev pointed to the need to restart the contact group, while the Tajik leader Emomali Rahmon stated that there is no legal basis for the contact group and proposed launching an extensive expert discussion of Afghan issues in the format of the SCO member states.

Against a backdrop of stalling UN initiatives on Afghanistan and the growing influence of the SCO in world affairs, the organization could take a firmer stance in the international discourse on Afghanistan. SCO countries cover more than 35 million km², 65% of the territory of Eurasia, and have a combined population of approximately 3.5 billion people, almost half of the planet, accounting for about a quarter of world GDP, and more than 15% of international trade.

In this respect, a potential transformation of the SCO is hoped for, as voiced by Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev at the Astana summit: “In the context of rapid global changes, we face the urgent task of further improving the SCO’s activity. The ongoing process of expanding the organization opens new opportunities and gives impetus to its development,” he stated. Indeed, Kazakhstan, which currently chairs the organization, has put forward “balanced proposals for transforming the organization into an even more effective multilateral cooperation mechanism” in particular strengthening the SCO Secretariat and the secretary-general.

Objectively, in the current era of turbulence, change and upheaval, when a global crisis of confidence is driving geopolitical conflicts and confrontations, the SCO should cultivate a new regional reality that excludes bloc and confrontational approaches to resolving international problems, which directly affects the entire system of continental and global security. None of the SCO member states are interested in another destabilization of Afghanistan. The mission of the country, historically a geopolitical buffer and a site for proxy wars, should be rethought, and Afghanistan should serve as a link in the SCO space between Central Asia and South Asia, as well as between the north and south of Eurasia.

At the same time, the national interests of all SCO member states are closely linked with the situation in Afghanistan, which should make this a key issue on the organization’s agenda. All the countries interested in future large-scale economic projects in Afghanistan are members of the SCO. These projects include the trans-Afghan railways, the North-South Transport Corridor, and the Central Asian branches of the New Silk Road – which are part of the Partnership Network concept of strategic ports and logistics centers that are being developed within the SCO. In addition, the SCO countries have direct economic interests in other projects, like the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) gas pipeline, the Central Asia–South Asia (CASA-1000) power project, and mining in Afghanistan.

Today’s Afghanistan, following the withdrawal of Western coalition troops, offers the SCO more opportunities to promote the interests of its members in the country. But what is preventing the SCO from taking a firmer stance on Afghanistan? One obvious factor is the need to transform the organization itself, as voiced by the Kazakhstani president.

The new goal of the SCO in Afghanistan could be combining and coordinating the efforts of its member states on trade, and economic as well as political issues. The SCO could act as an agent of the political process on Afghanistan as part of a broader mission to take on some of the most challenging issues of international relations, with the rights and responsibilities of the SCO as an international organization expanded. This is exactly what Astana has in mind.