DUSHANBE (TCA) — Authorities in Tajikistan continue imposing restrictions on the private lives of Tajik citizens in the name of combating religious extremism. Such moves, however, may cause the opposite effect, driving Tajik Muslims into the hands of banned Islamist organizations. We are republishing this article by Edward Lemon on the issue, originally published by The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor:

In early September, six million mobile phone users in Tajikistan received text messages telling them to “respect traditional clothes” and “make it a tradition to wear traditional clothes.” The messages, sent at the behest of the State Committee on Women’s and Family Affairs, are the latest stage in a government campaign to suppress Islamic clothing in the name of countering violent extremism (Saama TV, September 5; Daily Sabah, September 17). On August 28, President Emomali Rahmon signed amendments to Article 14 of the 2007 Law on Observing National Traditions and Rituals, stipulating that individuals must “wear traditional and national clothes” at so-called “traditional” gatherings, such as weddings and funerals (President.tj, August 28).

Contrary to many English-language reports, the new legislation does not ban the wearing of the hijab outright. Instead it restricts what citizens can wear to specific events. Nonetheless, it constitutes another government attempt to regulate the private lives of citizens in Tajikistan. At present, the amended law does not outline any punishments for those caught breaking the law at ceremonies. But such punishments are likely to be introduced soon, according to Hilolbi Qurbonzoda, chief of the lower chamber of the parliament’s Committee on Social Affairs (News.tj, September 7).

Officials in Tajikistan have long placed visual appearances at the forefront of their counter-extremism efforts, promoting “national” dress over “foreign” Islamic clothing. Those who wear beards or hijabs are often portrayed as potential terrorists. In a speech delivered on Women’s Day in 2015, President Rahmon condemned females who wore foreign clothing, saying that they were propagating “alien” extremist ideas in the country (President.tj, March 6, 2015). Wearing Islamic clothing does not form an important part of being Muslim, according to officials. In August, for example, the president said that “devotion to God is expressed in the heart, not with dress, or the hijab” (Akhbor, August 23).

Tajikistani authorities have introduced policies in recent years to promote these ideas. These policies are twofold: they encourage individuals to wear “national” dress and discourage Islamic or Western clothing. Officials argue that citizens should wear national dress: a suit with a clean-shaven face for men and a colorful, long, two-piece ensemble with a headscarf worn above the ears by Tajik women. In July, Minister of Culture Shamsuddin Omurbekzoda announced the establishment of a committee to “help design clothes for men and women” (RFE/RL, July 21).

But simply promoting national dress is not enough. In 2005, the minister of education issued a statement banning hijab in schools. And in 2007, education authorities instituted a mandatory dress code that reinforced the ban. Not only has the government established laws to regulate clothing in specific settings, police officers have led a more informal campaign against those outwardly showing signs of their faith. A video that circulated widely on social media in February 2016, for example, shows police in Khujand detaining and swearing at women wearing hijabs (YouTube, February 20, 2016).

Assessing the scale of this informal campaign remains difficult. Statistics that are presented as facts are not sourced and are devoid of any explanation as to how they were reached. An oft-circulated figure that 8,000 women were stopped in early August in Dushanbe by officials telling them how to dress properly, for example, seems to have originated from the Russian website Umma 42 (Umma 42, August 11). But the article does not name any source or explain the figure. Conversely, the scale of the abuses is potentially being underestimated, as many victims of religious persecution remain silent, fearing reprisals if they speak up.

As academic Marintha Miles has argued, the campaign against individuals who grow beards or wear hijabs is unevenly enforced and is not random (Centralasiaprogram.org, May 27). Many are connected to members of the political opposition. With the crackdown on Islam and the political opposition in recent years, thousands of citizens have fled the country, seeking refuge in Russia, Turkey and Europe. To place pressure on these exiles, the government has targeted their family members still in the country, often using their dress as an excuse to do so.

The effectiveness of these measures is questionable to say the least. Conversely, the government’s perceived campaign against Muslims has been utilized by terrorist groups, most notably the Islamic State, for recruitment purposes. In the video revealing his defection to the Islamic State in May 2015, Gulmurod Halimov, the former head of Tajikistan’s military police, laid the blame for his move on the authorities. He accused them of ordering a hijab ban in Dushanbe and paying prostitutes $10 each to appear in hijabs in a video that state media used to discredit Islam. “You passed a law prohibiting prayer on the streets. But God says you can pray anywhere,” Halimov stated (YouTube, May 28, 2015).

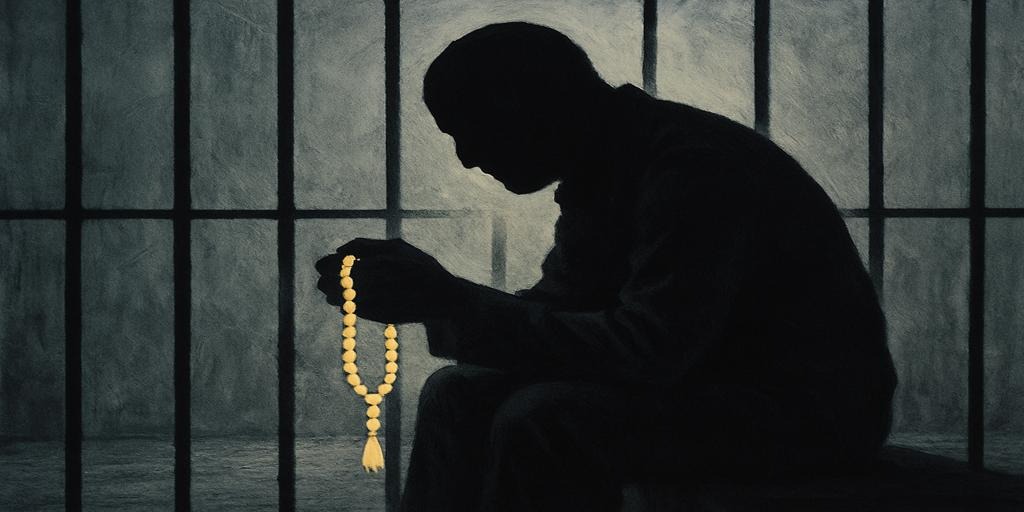

The link between state policies and recruitment to extremist groups remains difficult to prove beyond doubt. And the actual scale of the abuses is difficult to measure. Yet, one thing is clear: many of Tajikistan’s Muslims are seeing their private lives and civil liberties restricted by the government. As the authorities consider further moves to counter extremism, Tajikistanis’ private lives will become colonized by the state more and more.