BISHKEK (TCA) — Through Iran’s Chabahar port, India has got access to the markets of Afghanistan and Central Asia states, with the possibility to reach Russian and European markets by land routes. We are republishing this article by Sudha Ramachandran on the issue, originally published by the CACI Analyst:

On November 11, a consignment of 15,000 tons of wheat arrived in Afghanistan from India via Iran’s Chabahar port. This is an important milestone for the three countries as it marks the operationalization of the transit trade agreement they signed in 2017. In addition, the first phase of the development of Chabahar port has been completed. It is expected to energize Iran’s economy and provide India with a gateway for overland access to Afghanistan and the Central Asian states. Importantly, landlocked Afghanistan now has another outlet to the sea, reducing its dependence on Pakistani ports. This will reduce Islamabad’s influence over Afghanistan.

BACKGROUND: Iranian President Mohammed Khatami mooted the topic of India developing Chabahar into a trade and transshipment hub during his visit to New Delhi in 2003. India at first embraced the idea enthusiastically but then its interest waned. It was concerned over the project’s economic viability, especially in the context of international sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program. Under pressure from the US to distance itself from Iran, India dragged its feet on the Chabahar project.

India’s interest in Chabahar port revived from 2012 onwards. US-Iran relations were improving and with nuclear-related sanctions on the Iranian economy being lifted in January 2016, the port’s economic prospects brightened. India’s ambitions to expand trade with and influence in Afghanistan and Central Asia had grown but Pakistan refused India overland access to Afghanistan. Consequently, Indian investment in Chabahar port’s development as a gateway for overland trade to and through Afghanistan became necessary.

Importantly, China’s presence in the region has grown remarkably over the past decade. Not only has Beijing funded, built and begun to operate Gwadar port in Pakistan, but is also financing and constructing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a trade corridor linking Gwadar with China’s Xinjiang province. Worryingly for India, Chinese naval ships have docked at Gwadar.

Moreover, Beijing also demonstrated an interest in developing Chabahar port and Iran was not averse to this prospect. Concerned of being edged out of the project, Delhi expedited its participation in the Chabahar project. In May 2016, India signed an agreement with Iran to build and operate Chabahar port for ten years. New Delhi agreed to invest US$ 500 million in developing two terminals and cargo berths as well as other related infrastructure. A trilateral agreement signed by India, Iran and Afghanistan provided for transit trade through Chabahar.

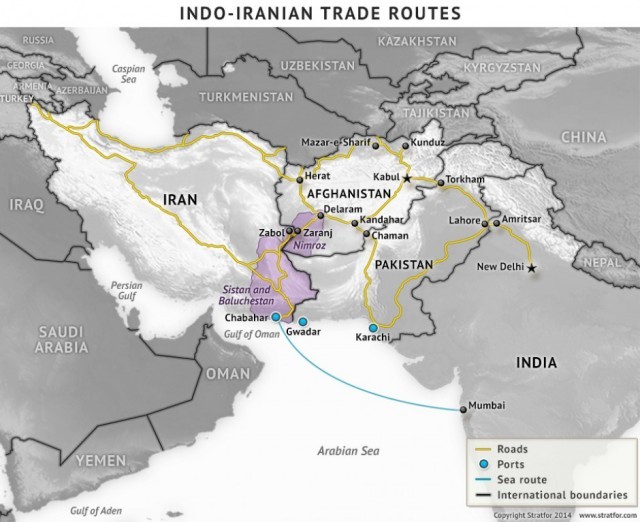

The plan is for shipments from India to be offloaded at Chabahar port, where the cargo would be loaded on to trucks and trains heading to Zahedan near Iran’s border with Afghanistan and onward to Zaranj in Afghanistan (the distance between Chabahar –Zahedan and Zahedan – Zaranj are 1,380 km and 200 km, respectively). Similarly, Afghan goods reaching Zahedan would be transported overland to Chabahar from where ships would carry the cargo to India and other countries.

IMPLICATIONS: Chabahar port has immense strategic value. Its location outside the Strait of Hormuz reduces the Iranian economy’s vulnerability to a blockade of the Strait by hostile powers. Situated on the Makran coast, it gives Iran direct access to the Indian Ocean.

Chabahar port is Iran’s only deep-sea port. Its development will enable Iran to receive high tonnage ships, which was not possible in the past, forcing Iran to route such ships to Dubai. Most international shipping is conducted via high tonnage cargo vessels and Chabahar can henceforth expect to benefit from the docking of these vessels, especially once Chabahar is linked to the International North-South Transport Corridor. Industrial development in and around the port complex is also likely to strengthen the Iranian economy and boost employment in Sistan-Baluchistan, Iran’s least developed province, where Chabahar is located.

For India, which has so far been denied overland access to Afghanistan and Central Asia by Pakistan, Chabahar port opens up enormous opportunities as it will function as a gateway to overland trade corridors linking India to resource-rich Central Asia and European markets.

Delhi has so far been airlifting cargo to Afghanistan, constraining its role in the war-torn country’s reconstruction. With overland routes from Chabahar to Afghanistan opening up, this is poised to change. In 2009, India completed the construction of a 215-km-long highway linking Zaranj with Delaram and several other cities on Afghanistan’s Garland Highway. This road network will multiply India’s access to Afghanistan and subsequently to Central Asia, and expand its influence in the region.

For Afghanistan, access to the sea via Chabahar port will ease its dependence on Pakistani ports, which are an uncertain option given the unstable relations between Islamabad and Kabul. This will reduce Afghanistan’s vulnerability to Pakistani pressure.

Afghan traders complain of harassment from Pakistani officials as their trucks are often prevented from crossing into Pakistan, and say that customs tariff rates are increased without warning. Overland routes via Iran to Iranian ports are safer, they argue, and more cost-effective than the routes to Karachi port.

Indeed, Afghan traders have in recent years opted to trade via Iran’s Bandar Abbas port. In 2008-09 nearly 60 percent of Afghan imports were transited through Pakistan. In 2016 this figure dropped to less than 30 percent. Afghan trade through Iran increased from 15-20 percent to 37-40 percent during the same period. Afghan trade via Pakistan can be expected to drop further when Chabahar port becomes operational.

According to Indian analysts, Pakistan’s main concern in light of these developments is losing its leverage with Kabul, rather than losing Afghanistan’s transit trade to Iran. Kabul is likely to gain greater confidence in dealing with Pakistan on the issue of transit trade and could, for instance, decide to deny Pakistan overland access through Afghan territory to Central Asia. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has repeatedly articulated this threat in recent years in response to Pakistan’s refusal to allow Afghanistan-India overland trade via Wagah.

Importantly, Chabahar could have a substantial impact on Gwadar port, just 72 km away. Gwadar is far more developed than Chabahar; it has a head-start of at least ten years. Transport links between Gwadar and Xinjiang are progressing and CPEC will also hook up with the network of the Belt and Road Initiative. These advantages notwithstanding, Gwadar needs to accommodate more trade than CPEC will bring – it also needs to transit cargo to and from Central Asia. Pakistan will need Kabul on its side to make this happen. The question is whether Kabul, newly freed from its dependence on Pakistani ports, will oblige.

CONCLUSIONS: The start of transit trade through Chabahar port is a momentous event. It is expected to pave the way for India’s increased trade with and influence in Afghanistan and Central Asia as well as Iran’s rise as a global transshipment hub. However, the most significant change it will bring is in Afghanistan’s relationship with Pakistan. By providing Afghanistan with another outlet to the sea, Chabahar reduces Kabul’s dependence on Pakistan. Indeed, it could provide Kabul with new confidence, even leverage in dealing with Pakistan, especially on trade matters.