BISHKEK (TCA) — As China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is poised to bring in huge economic opportunities for the Eurasian continent and Central Asia countries, we are presenting this article which was originally published on Asia Pathways, the blog of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI):

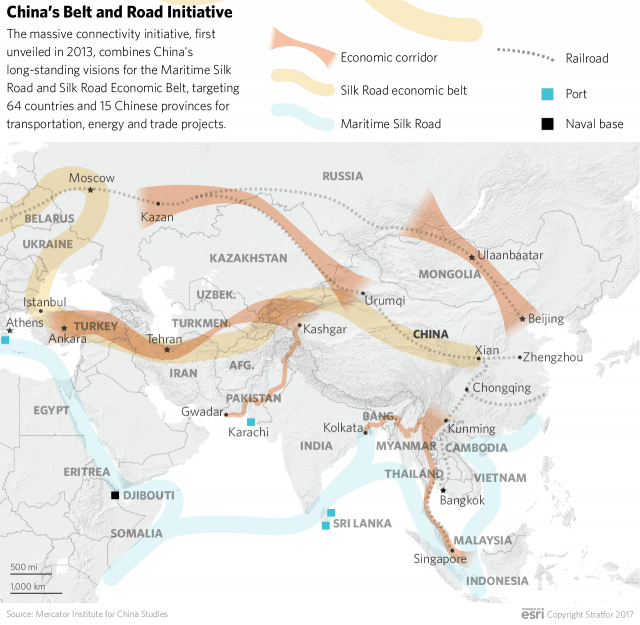

The New Silk Road Initiative was originally unveiled by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 and became known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). From the beginning, the initiative was presented as a reestablishment of the trade routes that were successful many centuries ago. The initiative was also a call for partner countries to accelerate transport infrastructure improvements and connectivity to boost trade. Through active diplomacy and intense public relations, 65 countries felt they had to join the initiative with the prospect of Chinese financial assistance.

Reviving the traditional Silk Road has, however, been on the agendas of Central Asian countries and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for a few decades, and the Asian Development Bank has contributed to it. Departing from the original route through Iran and the Middle East, alternatives have surfaced with routes through Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation. Container block trains between the PRC and Europe started in 2008. Services on this Eurasian bridge are now an interesting option for air services and shipping.

The maritime Silk Road is defined as the sea route from the PRC’s southwestern ports through the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean before reaching the Arabic Peninsula and the African shore. The route is reported to have started in the 8th century and is now busy and dominated by bulk carriers, oil and gas tankers, and container ships. The PRC has 170 ports along its long coast and, with the Port of Hong Kong, has regular shipping lines plying the new “container Silk Road.” Along the route up to the Suez Canal, Singapore, the Port of Tanjung Pelepas, and Klang with Colombo are major transshipment ports.

The first point to make is that there are no huge missing gaps in transport infrastructure to connect Asia to Europe by land or sea. Infrastructure improvements of a different scale may be needed on rail corridors. The corridors through Kazakhstan or Mongolia and the Russian Federation require only “fine tuning,” productivity enhancement, and, more importantly, rolling stock to meet demand. The situation is different on the historical Silk Road through Central Asia, the Black Sea, or the Middle East, where massive investments are required to turn the corridor into an effective transit route. For sea voyages, transshipments along the route are well managed and work effectively. All ports along the Maritime Silk Road have plans to remain competitive by responding to demand through productivity enhancement and capacity expansion. There is no obvious economic justification to construct new large transshipment ports as they would simply fragment total demand.

The second point to make is that the BRI is a clear win-win initiative for the PRC. It comes at an opportune time for the country. Supporting large infrastructure projects abroad would help resolve the overcapacity problems for both cement and steel (Miller 2016: 25). In addition, infrastructure, and more specifically transport infrastructure, has always been a major contributor to economic growth, and the initiative presents a new opportunity.

The expansion of the Eurasian land bridge is bringing a new era of prosperity to the centers of production in central PRC to cities like Chongqing, Chengdu, and Xian. The BRI is also used as an instrument to foster growth in peripheral provinces like Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Guangxi and to revive growth in the northeast. In fact, all provinces have been asked under the BRI to prepare qualifying infrastructure projects. Beijing has a massive foreign exchange reserve of approximately $3 trillion, and using the reserve for projects with returns higher than 5% or 6% is a better option than investing in United States bonds. Also, massive lending abroad would strengthen the acceptance of the renminbi as an international trade denomination. Chinese banks have ample funds to support the infrastructure diplomacy.

There are other motivations behind the initiative. The land bridge can provide better access to consumer markets in Europe, the Indian subcontinent, and Africa and also establish direct access to needed energy resources in the Gulf. For the maritime road, if expanding trade is elusive, asserting the PRC’s role as a world naval power brings additional political gains.

The third major point is that for BRI country partners, a win-win situation is far from guaranteed, and serious risks are involved. One risk is that political elites would, with easy Chinese financing, implement infrastructure projects with high political gains and limited economic benefits that are doomed to become “white elephants.” These mega projects would have the backing of government-to-government agreements with the involvement of Chinese banks. Chinese lenders rely entirely on borrowers to conduct economic, financial, and socioeconomic/environmental impact analyses. Transparency suggests that such projects should be debated in the public domain, but the restrictions on free press prevent a fair review of these contentious projects. The following examples illustrate this point.

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic’s rail construction from the Yunnan border to Vientiane is financed by the PRC. The estimated cost is $7 billion, while the Lao People’s Democratic Republic’s gross domestic product (GDP) stands at $12 billion. The revenue generated from the expected low traffic may not cover the cost of the toxic public debt increase. In Sri Lanka, under the past president and financed by Chinese banks, a new, grossly unused container terminal was built in the south at Hambantota. In December 2017, Sri Lanka could not repay the loan and decided to transfer the port to the PRC. Many other infrastructure projects were built (including a grossly unused new international airport in the south), and foreign debt to GDP during that period increased from 36% to 90%.

In recent years, in Malaysia, there has been a mushrooming of “dream infrastructure projects” that had been dormant before. The Malacca Gateway port project and Carey Island projects, both also supported by the PRC, raise disturbing questions. Malacca has no hinterland, and reviving past glory under the BRI might apply to tourism for cruise ship activities but not to a new container port. Along the Strait, capacity utilization stands at 75%. Future capacity expansions are well underway for Klang Port, Tanjung Pelapas Port, and Singapore. A new port on Carey Island, sponsored by the PRC, has no obvious domestic economic rationale. Another mega “dream” infrastructure project financed by the PRC, the East Coast Rail Line, has also raised questions. It consists of a rail line across the peninsula from Klang to Kuantan then to Kelantan State. The cost estimate for the rail line is RM55 billion for 620 kilometers of single track, with land acquisition likely to raise the cost. There are serious risks and it is hard to see how the expected traffic could make the project financially feasible.

BRI official documents stress that the initiative has no strings attached; geopolitical interests may, however, imply otherwise. Chinese foreign policy has a set of non-negotiable values that are expected not to be challenged by “friendly” partners (e.g., the Tibet Autonomous Region and Taipei, China). An example is the Chinese attitude to the Republic of Korea to the issue of Thaad anti-missile deployment.

The PRC, in official documents, has clearly stressed a non-intervention position with respect to country-partner decisions in selecting and implementing projects. It is entirely the responsibility of country partners to ensure economic and financial sustainability, but it seems that Chinese banks are prepared to finance risky projects for strategical geopolitical benefits.

There are three options, not necessarily exclusive, to consider for mitigating the risk of building white elephant infrastructures:

(a) For sensitive and contentious large infrastructure projects, Chinese banks decide to finance projects with developing banks like the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank that are known to conform to strict safeguarding criteria.

(b) All participating country members in the Silk Road Initiative agree when signing memoranda of understanding to submit large infrastructure projects for independent financial auditing.

(c) All participating countries agree to insert in memoranda of understanding between sovereign governments a request for feasibility studies to be fully accessible in the public domain.

The BRI initiative and the supported projects could turn out to be a beneficial “win-win” situation for partners if there are enough mechanisms in the countries to adopt a vigilant and transparent attitude. This is a tough order, but it can be done.