Right Place, Right Time: Central Asia Basks in Russia’s Eastern Energy Pivot

On January 1, with the closure of pipelines through Ukraine, deliveries of Russian gas to Europe came to a virtual standstill. Prices across the continent have ratcheted up in the first six weeks of 2025 and have now hit two-year highs.

In Central Asia, the effects of the Russo-European decoupling have also been profound. In 2024, Kyrgyzstan posted a 48% year-on-year increase in Russian gas imports, while Uzbekistan’s inbound gas purchases soared over 142% to $1.68 billion.

But while Gazprom’s reorientation has been a boon to Central Asia’s economies, this phenomenon appears to be more than short-term supply dumping due to the war in Ukraine. Rather, it is part of a lasting trend that could define the region’s, and the world’s, energy map.

Russia’s Supply Glut

In 2018, Russia exported a record 201 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas to Europe. The closure of the Yamal and Nord Stream pipelines had already brought these supplies down to 49.5 bcm by 2024 and will be further impacted by the cut in supplies via Ukraine. Despite some gas supplied via Turkstream and a steady trade in liquefied natural gas (LNG), Russian gas supplied to Europe is a fraction of what it once was.

The Central Asian market offers both short and long-term solutions to this.

“Most likely, Gazprom views its expansion into Central Asia as a partial and immediate solution to the challenge of finding new markets for its gas,” said Shaimerden Chikanayev, a partner at GRATA International, a law firm. “While the region cannot fully replace the volumes or profit margins previously achieved in Europe, it offers a readily accessible and stable outlet for Russian gas exports.”

Central Asia is accessible due to old Soviet pipelines that link the region to Moscow. These pipelines, known as Central Asia–Center, were originally built to take gas from Turkmenistan, via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Russia. This system has now been engineered to run in reverse. The pipeline has a capacity of around 50 bcm per year, but there are ongoing efforts to increase it.

Still, this is only a quarter of what was once supplied to Europe, nor are the revenues as lucrative. In 2023, the average rate charged by Gazprom to Uzbekistan for gas was $160 per thousand cubic meters (tcm), this compares to European prices that fluctuated between $200-400tcm throughout the 2010s.

For Stanislav Pritchin, head of the Central Asia sector at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO), Moscow, the price is not a major factor. “Russia of course sells gas to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan lower than the market price. This is a politically motivated decision. And this is not just because it is struggling with [selling to] Eastern Europe. Russia could sell it to Central Asia at market prices, but this is the Russian approach towards its allies in the region,” he said.

Central Asian Serendipity

For Central Asian states, these new supplies have come at a good time. Countries such as Kyrgyzstan are trying hard to increase the use of gas rather than coal for domestic heating. Meanwhile, traditional gas exporters such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are using the opportunity to buy cheap Russian gas while selling their own gas further afield, particularly to China.

“Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have faced difficulties in fulfilling their gas export obligations to China due to rising domestic demand,” said Eldeniz Gusseinov, co-founder of the political advisory firm Nightingale International Intelligence. Uzbekistan was forced to briefly suspend its gas exports in 2022, with Kazakhstan also slashing its supplies. “Access to Russian gas enables these countries to meet their domestic needs and, theoretically, frees up resources to fulfill their export commitments to China,” Gusseinov added.

Tashkent in particular is in desperate need of these supplies. “Uzbekistan used to be a leading gas producer, but they lack the resources, technology, and investment to develop [their gas industry],” said Pritchin. “They are now in quite a vulnerable situation because they can barely even meet their demands for basic gas and electricity.”

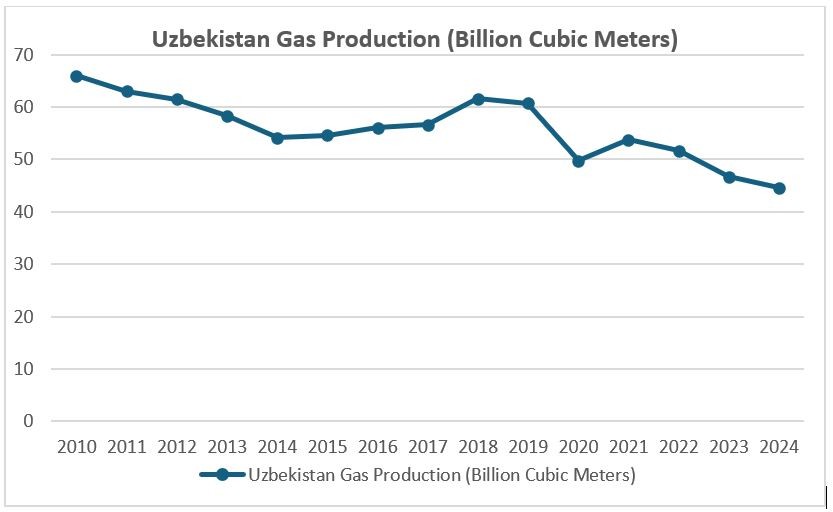

According to Uzbekistan’s official statistics authority, gas production has fallen by around a third from 66 bcm/year in 2010 to 44.6 billion in 2024. Pritchin forecasts that this decline will continue, despite the increased demand for electricity and gas from Uzbekistan’s growing population and economy.

Uzbekistan’s gas production has declined over the past decade. Credit: Joe Luc Barnes. Sources: 2010-2023 Stat.uz; 2024 figure as reported in The Tashkent Times

Chikanayev refers to the paradoxical situation where resource-rich countries such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are struggling with energy resources as the cobbler without boots. “Both [countries] have failed to invest adequately in their gas and power sectors since the collapse of the USSR. This includes neglecting the development of new gas fields and modernizing energy infrastructure,” Chikanayev said.

Uzbekistan has repeatedly stated that it intends to raise gas production to 62bcm as part of its Uzbekistan 2030 strategy, but the trend does not look positive.

No European Comeback

The increase in Russian gas imports is not without its critics. One fear is that Russia may simply abandon Central Asia and seek to prize open its old European markets should a peace deal be agreed in Ukraine.

Pritchin does not think so. “Even at the end of the special military operation, I don’t think the situation will dramatically change,” he said, adding that reopening pipelines between Russia and the EU is a decision for the Europeans, and even if there is re-engagement from Europe, the expansion of the Central Asian pipelines provides diversification.

Gusseinov agrees – “Diversify or die has become the prevailing mantra nowadays. Russia will want to remain at the center of Eurasian processes; [gas] allows the state to wield considerable geopolitical influence in the region with relatively modest resources.”

As evidence of Russia’s long-term plans for the region, he also points to a fifteen-year agreement signed at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum 2024 between Sanjar Zhareshov, chairman of QazaqGaz, and Gazprom’s Alexey Miller, undertaking to supply Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan with Russian gas until at least 2040.

Transit to China (and India?)

Kazakhstan is seen as essential to Russia’s strategic pivot. According to Chikanayev, “Kazakhstan has effectively replaced Ukraine as the key transit region for Russian gas.” He said that this does not necessarily mean that Kazakhstan will be reliant on the Kremlin, instead seeing it as mutual dependence, particularly if new pipelines are built to bring gas to China and India.

Currently, the Power of Siberia gas pipeline provides China with 38 bcm/year, but there are plans to increase this capacity. In a recent interview with Rossiya 24 TV Channel, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak announced that talks were underway between Russia, Kazakhstan, and China on the joint construction of a new pipeline with a capacity of 45 bcm/year – 10 bcm of this would be made available to supply the northern and eastern parts of Kazakhstan, with the rest going to China.

The other huge benefit of these cheap Russian supplies is that it allows Central Asian countries to export their own gas at higher prices. Both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan recently announced a surge in gas exports to China, despite imports also increasing. “This development supports the assumption that Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are purchasing cheaper gas from Russia and reselling their own freed-up gas volumes to China at higher prices,” said Chikanayev.

Another prize is potentially even greater. For over a decade, Russia and India have discussed a pipeline to connect the two countries. However, the length of the route, mountainous terrain, and instability in Afghanistan have all conspired to keep such an option off the table.

“However, in the context of the new geopolitical realities – such as Russia’s pivot away from Europe and its growing focus on Asia – there may now be additional arguments in favor of revisiting this direction,” said Chikanayev.

The arrangement makes sense – on the one hand, the world’s most populous nation with limited natural resources, on the other, an enormous gas supplier. Should Central Asia be able to connect the two, it could be very lucrative.