In recent years, a new generation of Uzbek artists has begun to reshape how culture, history, and identity are visually narrated. Among them is Oyjon Khayrullaeva, whose practice moves fluidly between photography, digital collage, and large-scale public installations.

Born after independence and largely self-trained outside formal art institutions, Khayrullaeva works with inherited visual languages such as Islamic ornament and traditional textiles, reassembling them into contemporary forms that speak to the present moment.

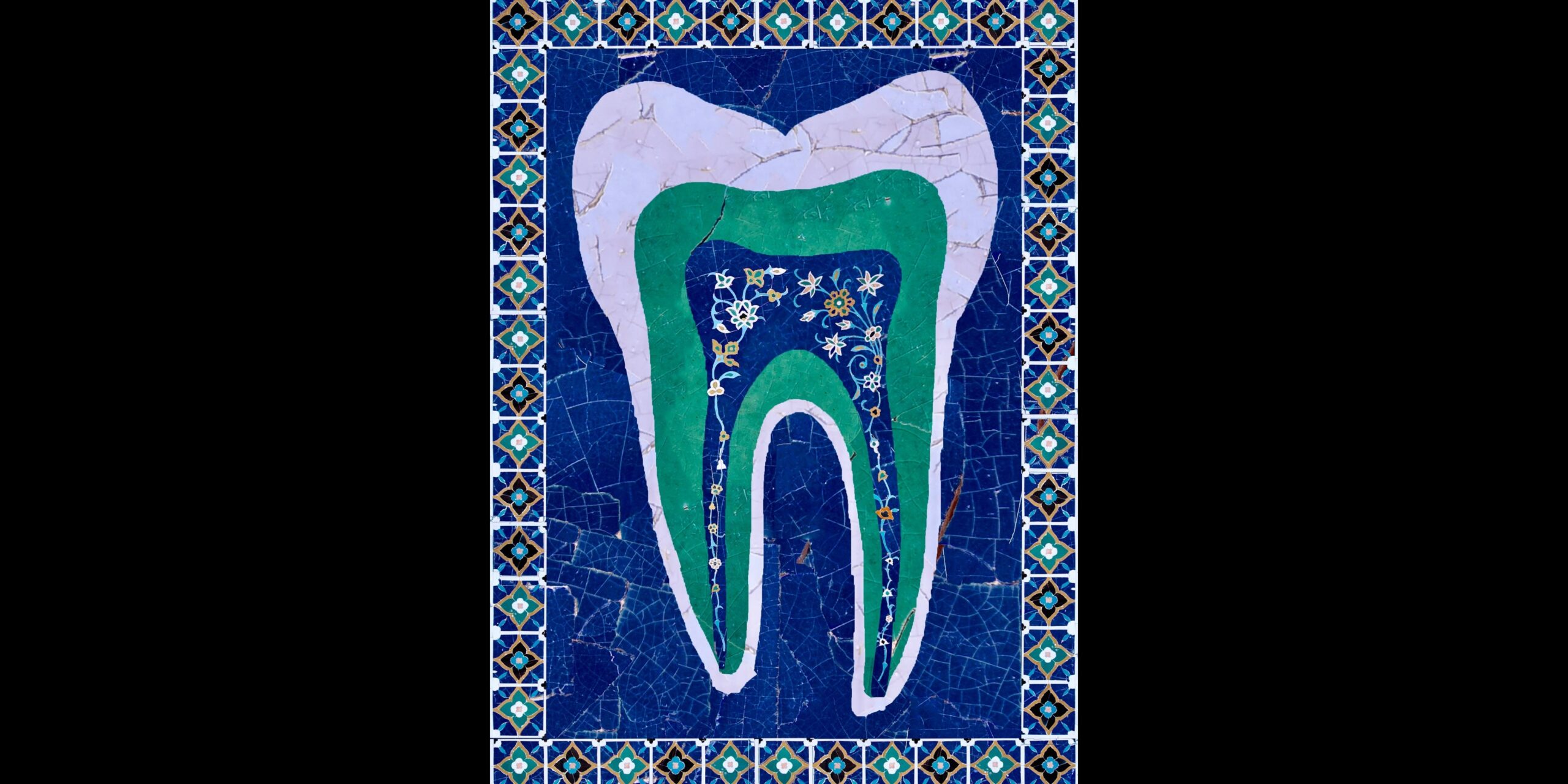

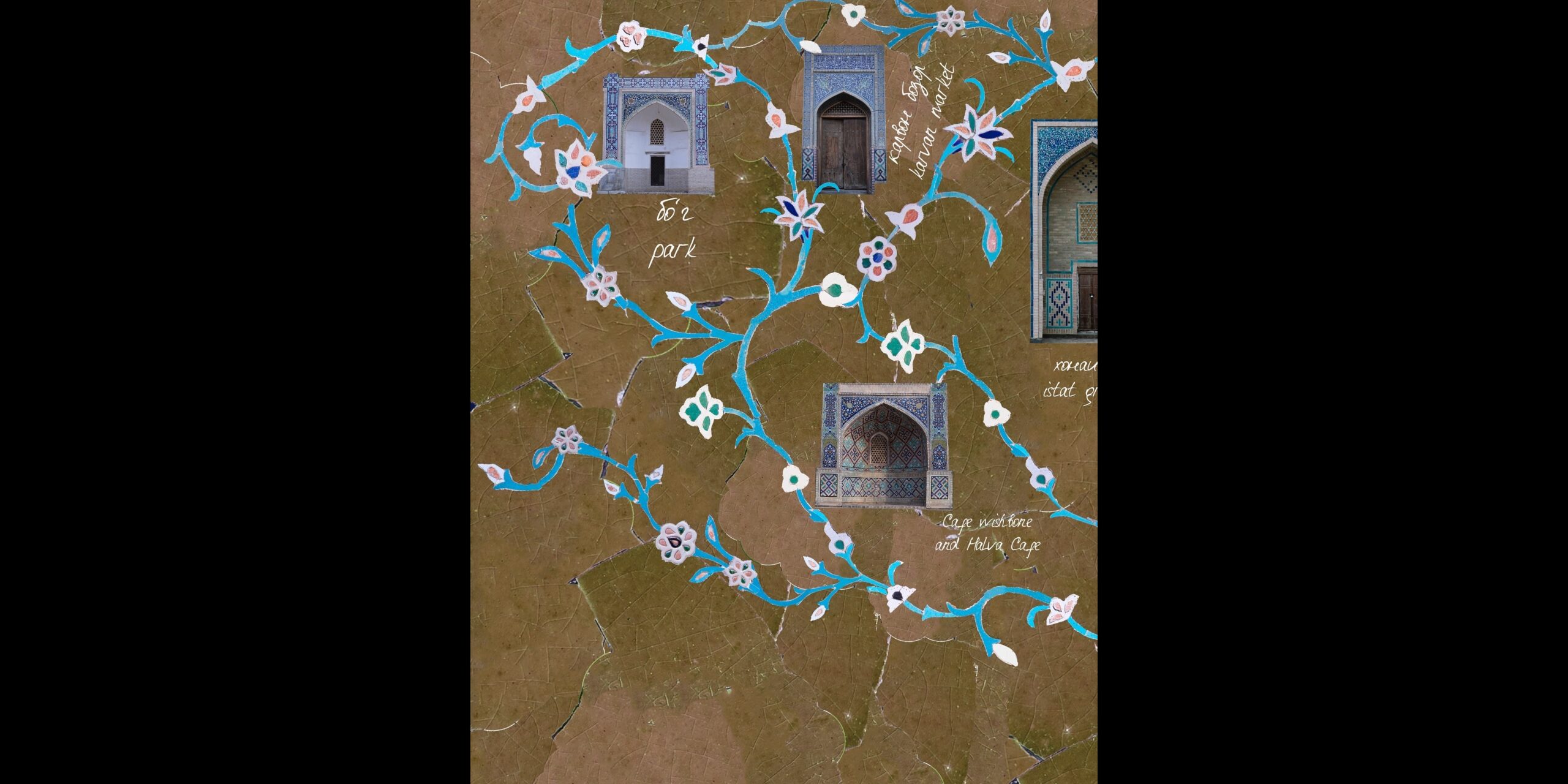

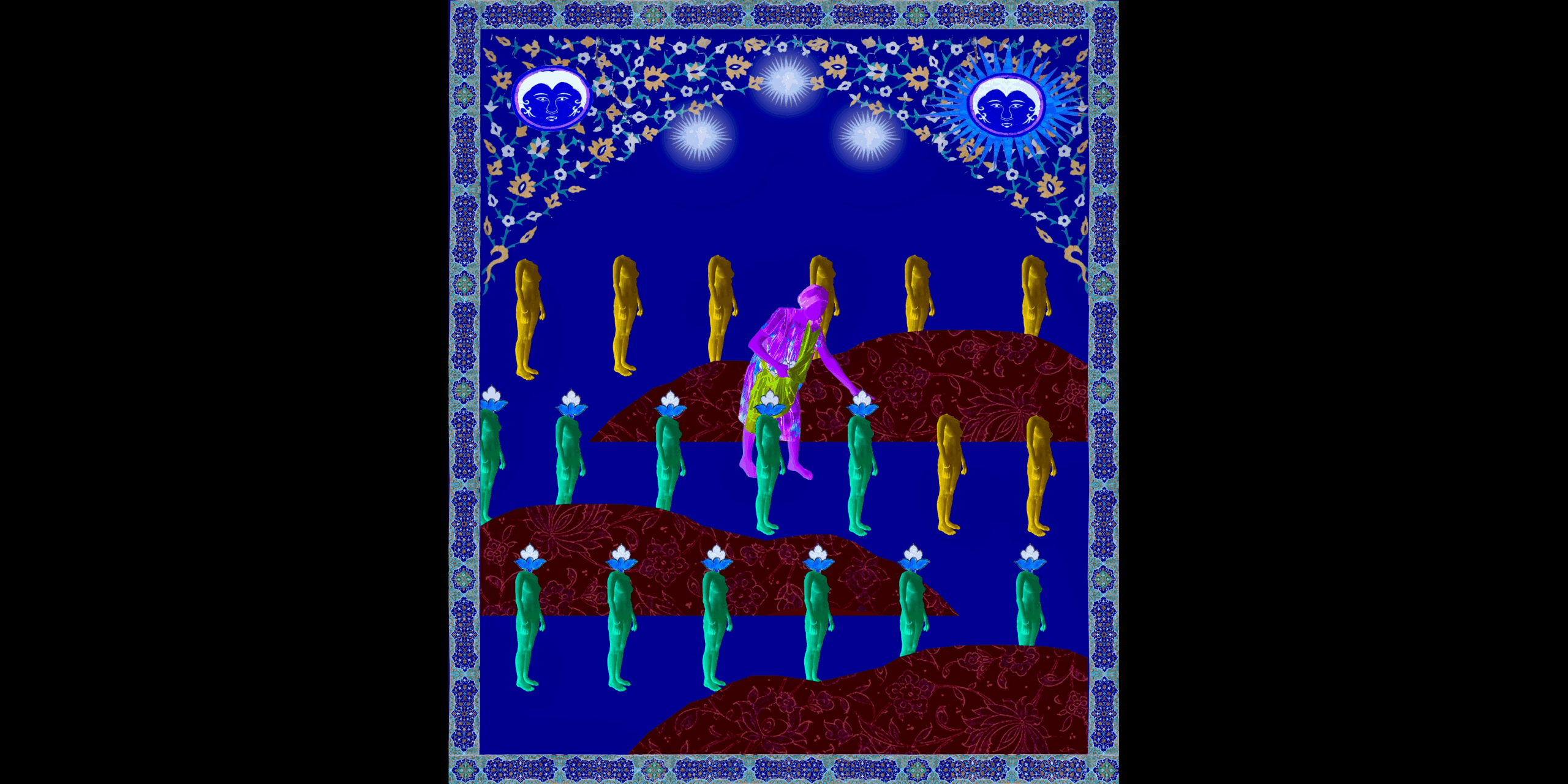

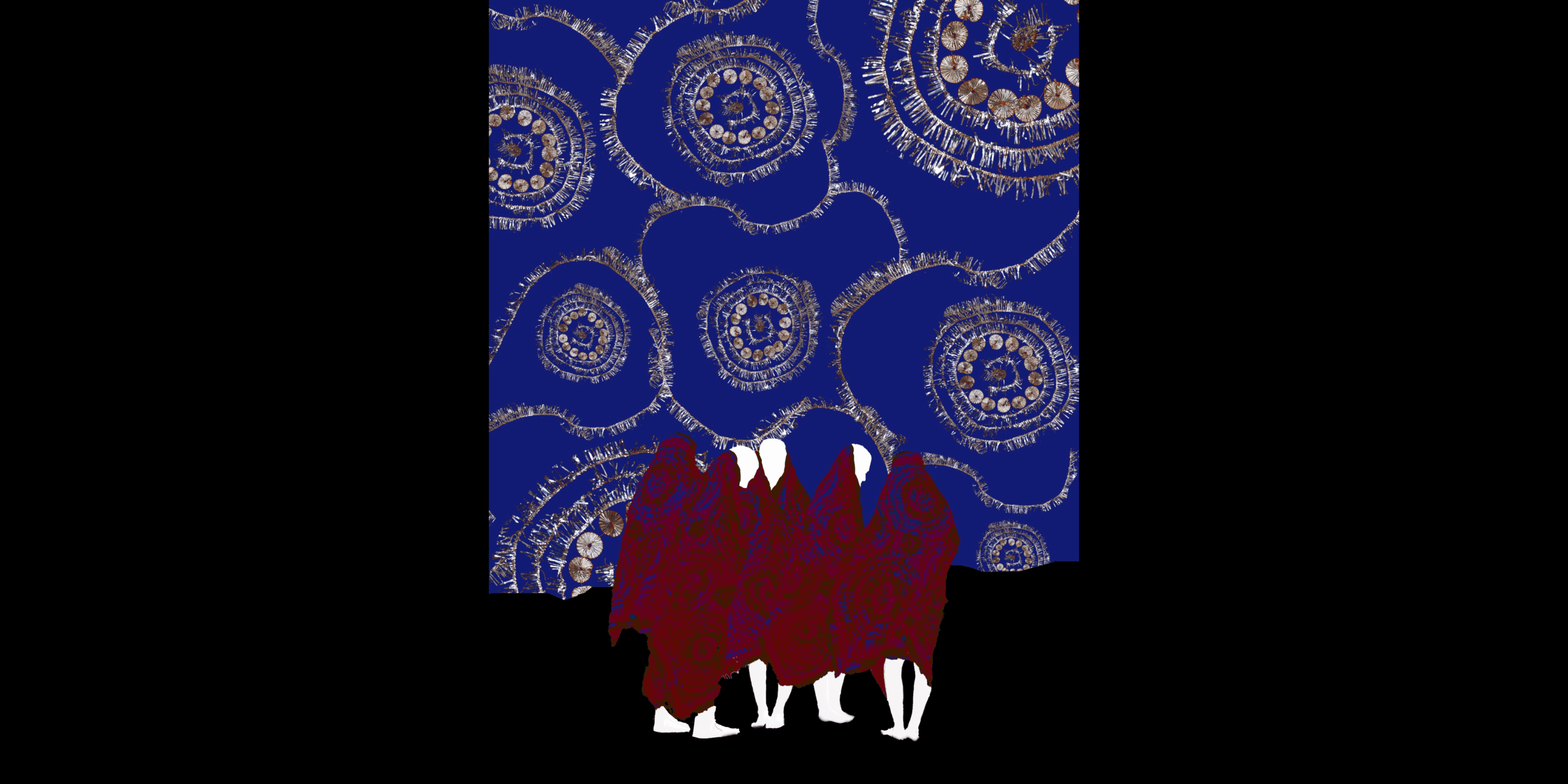

Her recent project for the Bukhara Biennial, called “Eight Lives,” marks a turning point in this exploration. Installed in the public and historical spaces of the ancient city, the work consists of monumental mosaic organs that connect physical vulnerability with emotional states and collective memory. Through the human body, Khayrullaeva maps experiences of anxiety, healing, spirituality, and social pressure, transforming ornament into anatomy and architecture into inner landscape.

The Times of Central Asia spoke with the artist to trace how Eight Lives emerged, how collaboration with mosaic masters shaped its final form, and how audiences in Uzbekistan are responding to seeing contemporary art in public spaces.

TCA: Can you tell me about your beginnings as an artist? Did you always want to become one?

Khayrullaeva: From early childhood, my parents noticed that there was something a bit unusual about me. My father has always called me – and still does – an “alien,” because I’m probably the only person in my family who chose a creative path. No one else in my family has been involved in art, at least not for the past seven generations.

I was always a creative child, but I never imagined that I would become an artist. As a child, I tried many things; I went to music school, studied piano, and attended various creative clubs. Still, the idea of pursuing art professionally never crossed my mind.

Becoming an artist was, in many ways, an unexpected turn in my life. For a very long time, honestly, until around the age of 24, I had no clear idea of what I wanted to do or what my profession would be. I was never certain about it.

So yes, life is an interesting thing. You never really know where it’s going to lead you.

TCA: Your artistic journey began with photography before evolving into digital collage. How did your early work in photography shape the way you now approach layering, texture, and composition in your digital pieces?

Khayrullaeva: When I was around 17 or 18, I became interested in photography. At that time, I didn’t have a camera, so I was shooting with my phone. For my birthday, I was given some money, and I decided to use it to buy a camera. My father added a bit more, and I bought my very first one.

It was an incredible feeling taking photos, holding the camera, and shooting. Mobile photography and working with a camera are completely different experiences, and that difference brought me so much joy. I remember the pure pleasure of photographing everything around me. Naturally, I started with my friends.

Very quickly, I realized that I was drawn to portrait photography and staged images. I was interested in creating surreal scenes, something slightly unreal. I still keep my very first photographs taken with that camera. I intentionally printed them and put them in frames to remind myself why I chose this path in the first place.

There are moments when you want to quit everything; that happens to everyone, it’s normal. Those photographs are there to remind me that this path was never about achievements or results, but about enjoyment. I understand that without creativity, my life would lose its meaning. I live through creativity, and I simply cannot imagine myself without it.

When I decided that I wanted to dedicate my life to photography, I received a harsh comment from my father. He didn’t believe that creativity could be a profession. I clearly remember him saying that art could only ever be a hobby, not a career. Because of that, I had to choose a different path and enrolled in a university in Europe, studying tourism and hospitality.

That was the beginning of a very dark chapter in my life, a descent that eventually led to new discoveries in my creative practice. Studying something that wasn’t aligned with my inner world pushed me into a severe depression, one that I struggled with for almost three years.

Eventually, I returned to Tashkent. Despite my father’s disapproval, I went back to photography. I started by taking courses, learning the technical foundations of the medium, while the intuitive side had always been there. Soon after, my practice shifted sharply toward collage.

I don’t regret going to Europe or going through depression. It opened something new within me, as if a third eye had awakened. That experience became the source from which my later work began to flow.

Now, on the contrary, my father says that he is very proud of me and very happy for me, and now he truly believes in it. I always tell myself: everything that happens, happens for a reason, and ultimately, for the better.

TCA: Your collages often incorporate elements such as Suzani embroidery and historical mosaics. How do you decide which cultural motifs to bring together, and what guides your process of blending tradition with contemporary expression?

Khayrullaeva: The process always happens in different ways. Sometimes, certain elements inspire me to create a specific work. For example, I have one of my mother’s Suzani embroideries, her wedding Suzani, which is embroidered with golden tinsel. It’s quite unusual, though it was popular in the 1980s and 1990s. That piece inspired several of my works.

Other times, an idea simply appears first, and then I look through all my photographs, mosaics, and Suzani pieces. If something fits, I use it. Or sometimes I already know exactly which photographs I want to use for a particular idea. I’ve worked with these photographs and mosaics for so long that I’ve almost memorized all of them. This makes it easy for me to organize the process in my head and work calmly. I still rely a lot on intuition.

More broadly, I’ve always been interested in combining something old with something contemporary. At the beginning of my journey, when I was reviewing all these photographs and mosaics, I thought, Why not create something new from them? I wanted to give traditional mosaics a new life, reinterpret them, and use them in contemporary contexts.

TCA: How do you envision digital tools transforming the landscape for artists in Uzbekistan?

Khayrullaeva: In the past, traditional fine art education played a very dominant role, but today its influence is gradually weakening. I see a huge number of young artists actively working with digital tools and technologies, and every year there are more and more of them, especially among the younger generation. This makes me genuinely happy, because art should never remain static.

Digital tools offer artists greater freedom and access to knowledge, to audiences, and to an international context. They allow traditional forms to be reinterpreted rather than rejected, encouraging hybrid practices that move beyond local systems and expectations. I believe it is precisely in this space between heritage and the digital present that a new artistic future for Uzbekistan is currently taking shape.

TCA: I was curious to know about Меҳргон | Mehregan | Harvesting. Can you tell me how you conceived that piece?

Khayrullaeva: I think it’s probably connected to a deep sense of frustration and injustice towards artists. Unfortunately, there’s still a lack of recognition for artists here; their work is often undervalued, and many exhibitions or projects are either unpaid or very poorly paid. I had this anger inside me, and I wanted to channel it into this piece.

In this work, as you can see, I juxtaposed cotton, the process of harvesting it, which involved exploitation in Soviet times, with the exploitation of artists today. To me, these situations are similar – work that requires effort and time often doesn’t receive proper acknowledgment or compensation. I wanted to highlight this parallel.

TCA: Your work tackles themes like identity, patriarchy, and uyat, shame. Is it somehow still taboo to speak about these themes in Uzbekistan?

Khayrullaeva: No, and it hasn’t been like that for a long time. There is growing awareness among the population, especially among women. It’s as if they are awakening, which is uplifting and inspiring. Things are changing, for example, a recent law addressing violence against women was developed by activists from the media project “Ne Molchi. UZ,” my good acquaintances.

Although taboos are gradually loosening, social pressure and stereotypes still exist, especially in more conservative regions. But art plays an important role here; it allows these topics to be discussed through images and stories, creating space for dialogue and reflection. Personally, I find it very encouraging to see women and young people beginning to speak openly about difficult issues; it inspires and motivates me to continue my work.

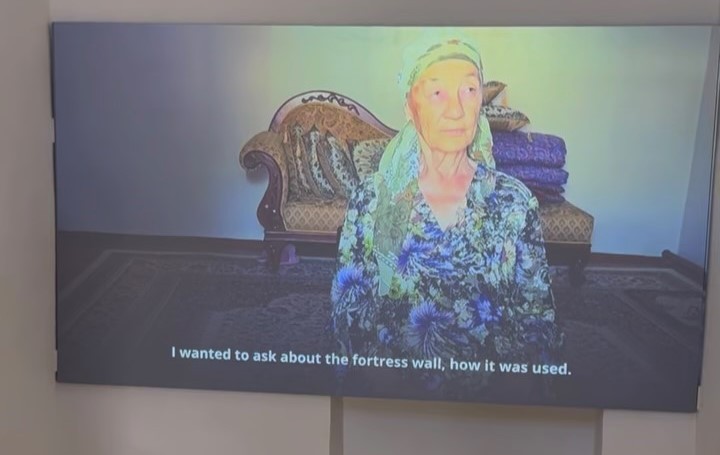

TCA: A very strong video piece you presented in Bukhara is “Grandmother’s stories.” How did you create that?

Khayrullaeva: This is an archival video of my grandmother. I started filming it about two years ago. One day, I realized that she was the only grandmother I had left, and I wouldn’t be able to remember all the stories she told me. So, I began recording them on video to preserve them and later pass them on to my nieces, nephews, brothers, or sisters who might be interested in learning more.

My grandmother is the only one who knows these stories, and unfortunately, no one paid much attention to them before I started asking. It was very important to me, and I believe it’s important for my family as well.

Later, the curator Diana Campbell, hearing the stories connected to medicinal herbs, suggested including them in the biennale. I then filmed additional footage showing what these herbs were, what rituals were performed, and the objects used, so viewers could better understand.

The final video is about 30 minutes long. Of course, these are just small excerpts; I had filmed much more, but those are personal family stories that I did not include in the biennale context.

TCA: Your work, Eight Lives, grew from a deeply personal exploration of bodily pain into a public installation. Can you tell me how you worked on that piece?

Khayrullaeva: The idea came to me in 2023 in Samarkand, at the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis. The mausoleums are completely covered in mosaics, and they are incredibly beautiful. At that time, I was in a process of healing and searching for forms of self-expression. It was then that I discovered collage and primarily began working with Islamic architecture.

At Shah-i-Zinda, I noticed mosaics with floral ornaments called islimi. Several mausoleums were almost entirely covered with these elements. I studied them closely and realized that they reminded me of veins and vessels in the human body.

Some time later, my anxiety intensified as a side effect of depression. It manifested in my body, in my heart, stomach, intestines, and nervous system. One day, I experienced severe tachycardia and had trouble breathing. I felt sharply how complex the human body is.

That was when I had the idea to use these floral elements to construct a heart. Then I created lungs dedicated to my mother. Later, I made all seven organs.

TCA: Sufi concepts appear in your work. Is Sufism part of your background?

Khayrullaeva: Sufism came to me after my depression, during my healing process. I had many existential questions, and Sufism gave me answers. I feel very connected to this philosophy. It has a therapeutic effect on me.

TCA: Collaborating with mosaic masters must have been fascinating. What did you discover?

Khayrullaeva: There were technical challenges, such as color matching. Some digital details were too small to translate into mosaic, so I had to adapt them. But overall, it was a very successful experience.

TCA: Are you working on something new?

Khayrullaeva: Yes, but I’m not ready to share. I’m continuing my series on the human body.