For Turkey, a NATO member and EU hopeful, the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) is an instrument that helps Ankara increase its presence in the strategically important region of Central Asia. For Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, the Turkish-dominated group seems to be a tool that allows them to achieve their economic goals, while also continuing to distance themselves from Russia.

Although Moscow still has a relatively strong foothold in Central Asia, it does not seem able to prevent the growing role of the Organization of Turkic States in the post-Soviet space. This entity – whose members are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, while Turkmenistan, Hungary, and the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus hold observer status – has the potential to eventually serve as a counterbalance not only to Russian, but also Chinese influence in the region.

Since its foundation in 2009, the OTS has held ten summits of its leaders. Over this period, the intergovernmental organization’s working bodies have also convened dozens of times. On November 5-6 in the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek, the OTS heads of states will meet for the eleventh time to discuss the future of the Turkic world.

Although the agenda has yet to be announced, it is believed that the OTS leaders will seek to strengthen economic cooperation between its members. Currently, their major trade partners are nations outside the bloc. For instance, Turkey’s largest trading partner is Germany, Azerbaijan’s is Italy, while China has recently become Kazakhstan’s biggest trade partner with bilateral trade hitting $31.5 billion. For neighboring Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, China and Russia remain the most important economic partners.

One of the group’s major problems is the fact that its members, excluding Turkey, are landlocked countries heavily-dependent on Russia and China geographically. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, as major energy exporters, rely on oil and gas pipelines traversing Russian territory to reach their customers in Europe. It is, therefore, no surprise that the Organization of Turkic States governments’ agreed in September to create a simplified customs corridor, aiming at reducing the number of documents required for customs operations and customs procedures between OTS member states. In other words, they plan to increase trade among themselves.

According to Omer Kocaman, OTS Deputy Secretary-General, the Turkic nations are also looking to “continue cooperation to stimulate positive changes in their financial systems.” That is why the organization has recently launched the Turkic Investment Fund – the first joint financial institution for economic integration of the Turkic countries, with an initial capital of $500 million. Kyrgyzstan’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry announced on October 17 that, starting in January 2025, the Turkic Investment Fund will begin financing major joint projects in OTS nations.

However, in July, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev said that the current structure of the Organization of Turkic States does not meet its established goals, and that its budget is insufficient for their implementation. In order to change that, on October 19, ministers of economy and trade of the OTS nations met in Bishkek to discuss how to strengthen cooperation and the economic development of member states.

The economy is undoubtedly an important aspect of the OTS members’ cooperation, but it is not the only one. Culture – including language as its essential part – and history also play crucial roles in the Turkey-dominated group’s ambitions to create a unified Turkic world. It is the Turkic language that connects Turkey with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, which is why Ankara has reportedly been pressuring Astana and Bishkek to give up on using Cyrillic and switch to the Latin alphabet instead.

In January 2021, the Kazakh government announced its plans to transition to a Latin-based alphabet, although to this day Cyrillic remains widely used in the largest Central Asian country. Most recently, on September 11 the Organization of Turkic States agreed to adopt a common Latin alphabet consisting of 34 letters. But Kyrgyzstan, reportedly under pressure from Moscow, aims to maintain the use of Cyrillic – at least for now.

In the long-term, however, if Moscow continues to lose influence in Central Asia, Cyrillic is likely to become a thing of the past in the region that has traditionally been in Russia’s geopolitical orbit. Meanwhile, Turkey is expected to continue using the Organization of Turkic States as a mechanism that could help Ankara crowd Russia out not only of Central Asia, but also of the South Caucasus.

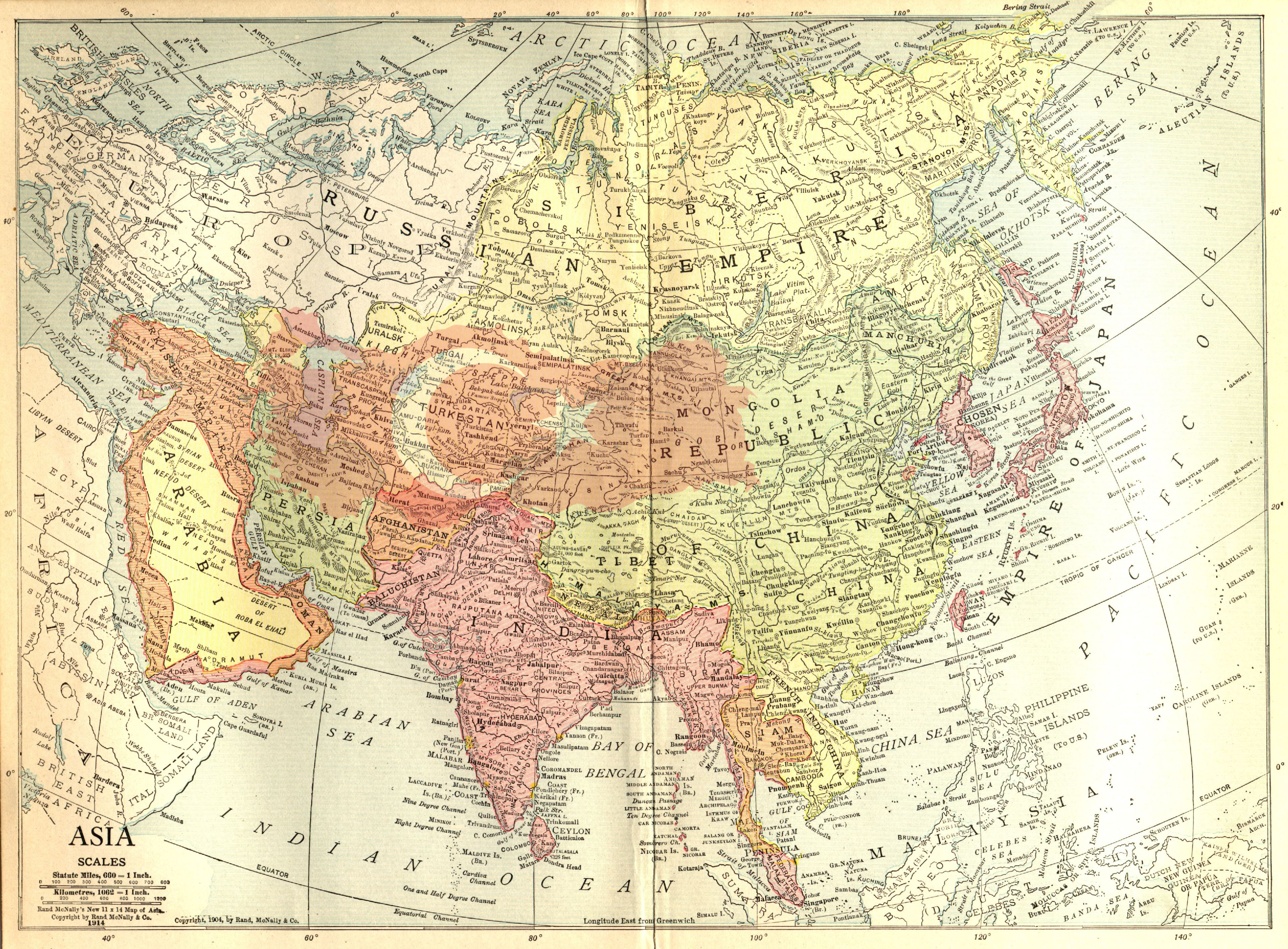

The OTS leading member does not hide its ambitions. In 2021, the leader of the Turkish Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), Devlet Bahceli, gifted a map of the Turkic World – which includes a significant portion of the Russian Federation – to Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Such a move drew criticism in Moscow, where many analysts are now unhappy about Ankara’s plans to replace the phrase “Central Asia” with “Turkestan” in its history curriculum. What seems to worry them more is the tendency to present Russia’s historical role in Central Asia in a rather negative light through the education system in most, if not all regional countries.

But the Kremlin, preoccupied with the war in Ukraine, does not seem to be in a position to effectively compete for the hearts and minds of Central Asians. Fully aware of that, Turkey is seeking to achieve its geopolitical goals in the region by developing closer ties with regional actors through the Organization of Turkic States – a tool that Ankara is expected to continue using in various fields, from education and the economy to foreign policy and even military affairs.