Urban Night Almaty: Creative Communities and the Future of Central Asia

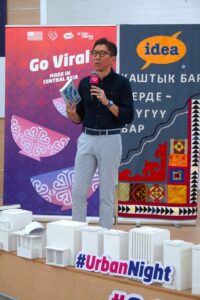

Ecology, entrepreneurship, and innovation in urban life were the central themes of Urban Night Almaty, a one-day festival held last Saturday in Kazakhstan’s largest city.

The event sought to answer a key question: Can small-scale initiatives and grassroots communities meaningfully improve life in a metropolis? Organizers and attendees alike believe they can.

The festival drew together a wide array of participants, recycling advocates, artists, artisans, confectioners, cosmetics producers, startup founders, writers, journalists, students, sociologists, urbanists, architects, and entrepreneurs, each contributing to a shared vision of sustainable, inclusive urban development.

@Eduard Galeev

“Each of us lives in our own information bubble, and events like this push us to step outside of it. We’re all different, but we can achieve something together,” said ecologist Pakizat Sailaubekova. “Looking at the people who came to the festival and how moved they are, it’s inspiring.”

Discussion and Decision-Making

Urban Night Almaty was organized around several thematic zones. One area was dedicated to public discussions on technology, education, and ecology.

Bekežan Kaigaliev, founder of Food Recycling and Aquajem, presented on the use of fly larvae to process organic waste in large cities. Alexey Kupriakov, founder of the Green Workout movement, shared ideas on integrating eco-friendly practices into urban planning.

Zhuldyz Saulbekova, CEO of the Almaty Air Initiative, spoke about technological solutions for combatting air pollution and chronic smog.

@Eduard Galeev

Other panels focused on educational innovation. Journalist and PR expert Anuarbek Zhalel, alongside Nursultan Amirkhan, product manager at Daryn.online, discussed promoting startups and integrating new tools in learning environments.

A separate session brought together alumni of U.S. internship programs. Among them were athlete and IT specialist Aina Dosmakhambet, lawyer Zhibek Karamanova, and Yerzhan Nauruzbayev, a Forbes 30 Under 30 honoree with professional experience across three continents.

Practice and Inspiration

Beyond the panels, attendees participated in workshops and creative performances. Highlights included a sports-themed cleanup organized by Kupriakov and an urban exploration of Almaty led by the GoroZhanym project.

An eco-themed market showcased small-scale producers offering food, toys, jewelry, souvenirs, and hygiene products. Many entrepreneurs shared stories of how their ventures, though modest in scale, contribute to making Almaty cleaner and more future-oriented.

@Eduard Galeev

“We often speak in terms of global problems, but it’s essential to respect action at the micro level,” said political analyst Dosym Satpaev. “Thanks to social media, even the smallest project can gain traction. The more of these we have, the stronger our creative economy becomes. These are the foundations for national stability, development, and retaining talent.”

Satpaev also hosted a futurology session addressing the challenges and prospects artificial intelligence presents for Central Asia.

The festival concluded with a tұsaуkeser ceremony, a Kazakh tradition that involves cutting a symbolic cord representing a newborn’s first steps. The cords, handcrafted by members of the Niti Dobra movement (which supports premature infants), symbolized renewal and the strengthening of ties between citizens and their city.

@Eduard Galeev

Regional Reach

“Our goal is to create a platform uniting entrepreneurs, startups, and those committed to transforming cities for the better,” said Elmira Karmanova, the festival’s organizer. “Urban Night Almaty is just the beginning, next week, we’ll bring the festival to Bishkek, followed by Dushanbe, Samarkand, and Ashgabat.”

Urban Night Almaty was held as part of the Go Viral program with support from the U.S. diplomatic mission in Kazakhstan.