Containerization is rapidly becoming one of the most talked-about topics in Kazakhstan’s logistics sector. Amid surging transit traffic, the question is increasingly raised: why, despite clear potential, is the domestic market still underutilized? What’s holding Kazakhstan back from making containerization a cornerstone of its integration into global trade?

Currently, transport costs account for up to 30% of the final price of goods in Kazakhstan, nearly three times the global average of around 11%. Experts agree that a systemic transition to containerized transport could speed up delivery times, cut logistics costs, and boost the competitiveness of Kazakhstani products. Yet progress remains sluggish.

A Priority Still in Waiting

In September, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev named the development of containerization as a strategic economic priority. Despite this, containers make up only 7% of domestic freight transport, less than half the global average of over 16%.

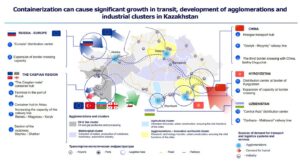

Meanwhile, transit volumes are surging. According to Kazakhstan Temir Zholy, the national rail company, container transit grew by 59% last year to 1.4 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU). The national target is 2 million TEU by 2030. Yet this growth is bypassing the domestic economy: Kazakhstan remains a transit bridge between China and Europe without yet unlocking containerization for its own industries.

Hidden Resources Still Untapped

Research by Russian consulting company Arthur Consulting suggests that Kazakhstan has the potential to containerize 50-55 million tons of domestic cargo, a volume capable of revitalizing the country’s entire logistics ecosystem.

So why hasn’t it happened? The reasons are well known.

First, infrastructure remains underdeveloped. Modern terminals capable of handling high volumes are lacking. Many transport routes lack essential repair facilities and service centers, meaning containers must often be returned without proper maintenance.

Second, there is a chronic shortage of containers and fitting platforms. This forces businesses to opt for cheaper, less efficient alternatives. Third, current tariffs make container transportation less attractive than road transport or covered railcars. Under such conditions, containerization appears more costly than beneficial. And lastly, there is a widespread lack of expertise. Some industrial players still don’t fully understand how to work with containers, optimize logistics, or implement modern transport solutions.

As a result, a significant portion of cargo is still transported the “old-fashioned way”, in covered railcars. This increases costs, extends delivery times, and limits access to multimodal transport routes.

Speaking at the New Silk Way transport and logistics forum, held in Almaty in September, Arthur Consulting partner Boris Poretsky described the sector as being “stifled” by systemic barriers. He emphasized the need for industrial companies to re-evaluate their logistics strategies. While nearly any cargo from bulk materials and liquids to heavy machinery can now be containerized, many exporters and consignees have yet to capitalize on the benefits.

Containers allow for door-to-door delivery without transshipment, reduce loading and unloading times, improve cargo safety, and offer maximum flexibility, whether by sea, rail, road, or even air.

@Dauren Moldakhmetov

A Global Shift

Worldwide, industries are rapidly adopting containerized logistics. The benefits are significant: 10-15% cost savings, reduced handling, greater cargo security, fewer supply chain disruptions, ESG compliance, and more efficient locomotive usage.

With urban growth, agglomeration, and the rise of e-commerce, demand for fast, reliable delivery is increasing. Containers are becoming the global standard.

Experts argue that containerization is no longer just a logistics tool. It is the infrastructural backbone of the modern economy.

Building a New Logistics Culture

Experts agree: Kazakhstan needs solutions from both the top down and the bottom up.

At the state level:

- A national containerization strategy;

- A reformed tariff policy;

- Private investment in logistics infrastructure;

- Integration with international transport corridors.

At the industry level:

- Terminal and service base modernization;

- Expansion of the national container fleet;

- Localized production of containers and fitting platforms.

At the business level:

- Investment in terminals and warehouses;

- Digitization of logistics processes;

- Shift to container-based delivery models.

If these steps are implemented in parallel, Kazakhstan could not only boost transit volumes but also establish a domestic containerized logistics economy that benefits shippers, exporters, and consumers alike.

Containerization isn’t just about packaging, it’s about speeding up trade. It makes Kazakhstani goods faster, cheaper, and more competitive in global markets.

In short, any serious discussion about economic modernization in Kazakhstan must include containers. They are a simple yet transformative tool capable of reshaping entire industries.