The launch of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan-Caspian multimodal corridor has generated significant interest as another attempt to expand Eurasian transport connectivity. A pilot shipment in the fall of 2025 demonstrated the technical feasibility of the new route: cargo transported from Kashgar, China, passed through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, reached Turkmenistan, and was then delivered to Azerbaijan via the Caspian Sea, continuing along the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway toward Europe.

Despite its evident geopolitical appeal, questions remain over the route’s long-term sustainability and commercial viability. The central question is whether this demonstration project can evolve into a regularly functioning transport corridor.

A Third Alternative Between the Northern and Middle Corridors

This multimodal route can be seen as a potential alternative to the two existing pathways: the northern route, China-Kazakhstan-Russia-Europe; and the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), or Middle Corridor, which passes through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, the South Caucasus, and Turkey.

The growing geopolitical risks along the northern route since 2022, combined with capacity limitations on the Caspian segment of the TITR, have spurred interest in a third option, a so-called “southern belt” traversing Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

Each country along this route has its own strategic calculus. Uzbekistan is seeking to overcome its “double continental isolation” and elevate its role as Central Asia’s transit hub. Kyrgyzstan is aiming to monetize its geographic position between China and the Ferghana Valley. Turkmenistan is developing the port of Turkmenbashi as an alternative to the increasingly congested hubs of Aktau and Alat. China, meanwhile, continues to diversify its westward overland trade routes.

The Uzbek Factor: Geoeconomics vs. Logistics

From Tashkent’s perspective, this corridor aligns with its long-term transport strategy. Analysts frequently cite Uzbekistan’s ambition to transition from a landlocked to a “land-linked” state with direct access to China, the Caspian Sea, and southern routes to the Indian Ocean.

The new route offers Uzbekistan three strategic advantages: alternative access to China via Kyrgyzstan, enhanced status as a regional transit hub, and deeper transport cooperation with Turkmenistan, including potential joint development of the Turkmenbashi port.

However, when shifting from geopolitical ambition to logistical execution, serious limitations emerge, many outside Uzbekistan’s control.

Kyrgyzstan: A Bottleneck in the Chain

Documents from the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) program highlight the continued challenges facing multimodal transport in the region, namely slow transit, poor modal integration, border delays, and outdated logistics technologies.

Within this corridor, Kyrgyzstan remains the primary bottleneck. Approximately 82% of its foreign trade by weight is transported by road, making the route through this mountainous country highly seasonal, expensive, and unpredictable.

According to the International Road Transport Union, Kyrgyzstan’s transport system faces severe constraints from alpine terrain, avalanches, and impassable mountain passes that render winter transport nearly impossible in many areas. It is therefore unsurprising that, following the pilot shipment, no major logistics operators committed to shifting regular cargo to this route.

The Caspian Sea: Structural Constraints

The Caspian Sea leg, anchored by Turkmenbashi port, presents another critical challenge. The limitations here are systemic rather than national. Key issues include insufficient fleet capacity, the absence of regular liner services, inconsistent schedules, weather-related disruptions, and fragmented tariffs.

While the Turkmenbashi port is competitive in several respects, it cannot alone address vessel shortages or the lack of regional coordination. Without structural reforms, Caspian routes, including this new corridor, will continue to operate at suboptimal levels.

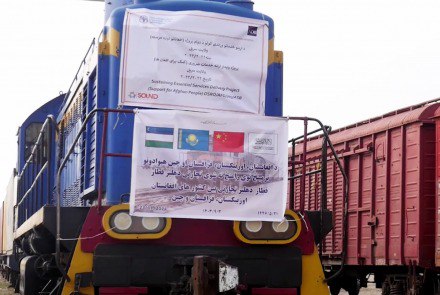

The CKU Railway: A Potential Game Changer

Some experts argue that the only transformational solution lies in completing the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway. This would reduce transport costs, enhance predictability, and eliminate seasonal constraints along the mountainous Kyrgyz section.

However, analysts caution that the CKU railway should be regarded as a regional connectivity project rather than a full alternative to the Northern or Middle Corridors. It would serve as a new axis of trade between China and Central Asia, rather than as a pan-Eurasian route.

The World Bank has categorized the CKU as a greenfield project in its “Middle Trade and Transport Corridor” report, highlighting financial and macroeconomic risks typical of infrastructure developments still in the design phase.

Geopolitics Outpaces Infrastructure

In its current form, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan-Caspian corridor reflects regional strategic ambitions more than infrastructure readiness. For Central Asia, diversifying transport routes has become essential to achieving geopolitical autonomy, yet infrastructure development still lags behind political aspirations.

This initiative is less about creating a fully functional Eurasian corridor and more about gradually shaping a new axis of regional connectivity. Its long-term economic sustainability will depend not on symbolic pilot shipments but on the participating countries’ ability to coordinate infrastructure investment, standardize logistics procedures, and align their strategic interests.