First, a young Kazakh schoolgirl in a black dress with a starched collar, her hair tousled by the wind of the Aral Sea, clutches a large Russian book tightly to her chest as she stands before a lonely school building in the middle of nowhere.

Then, a camel speaks: “Give me back the sea!”

“No!” cries a woman, her face hidden beneath a military hat. She stands before an abandoned edifice, her head wrapped in fur, her body strangely adorned with eggs.

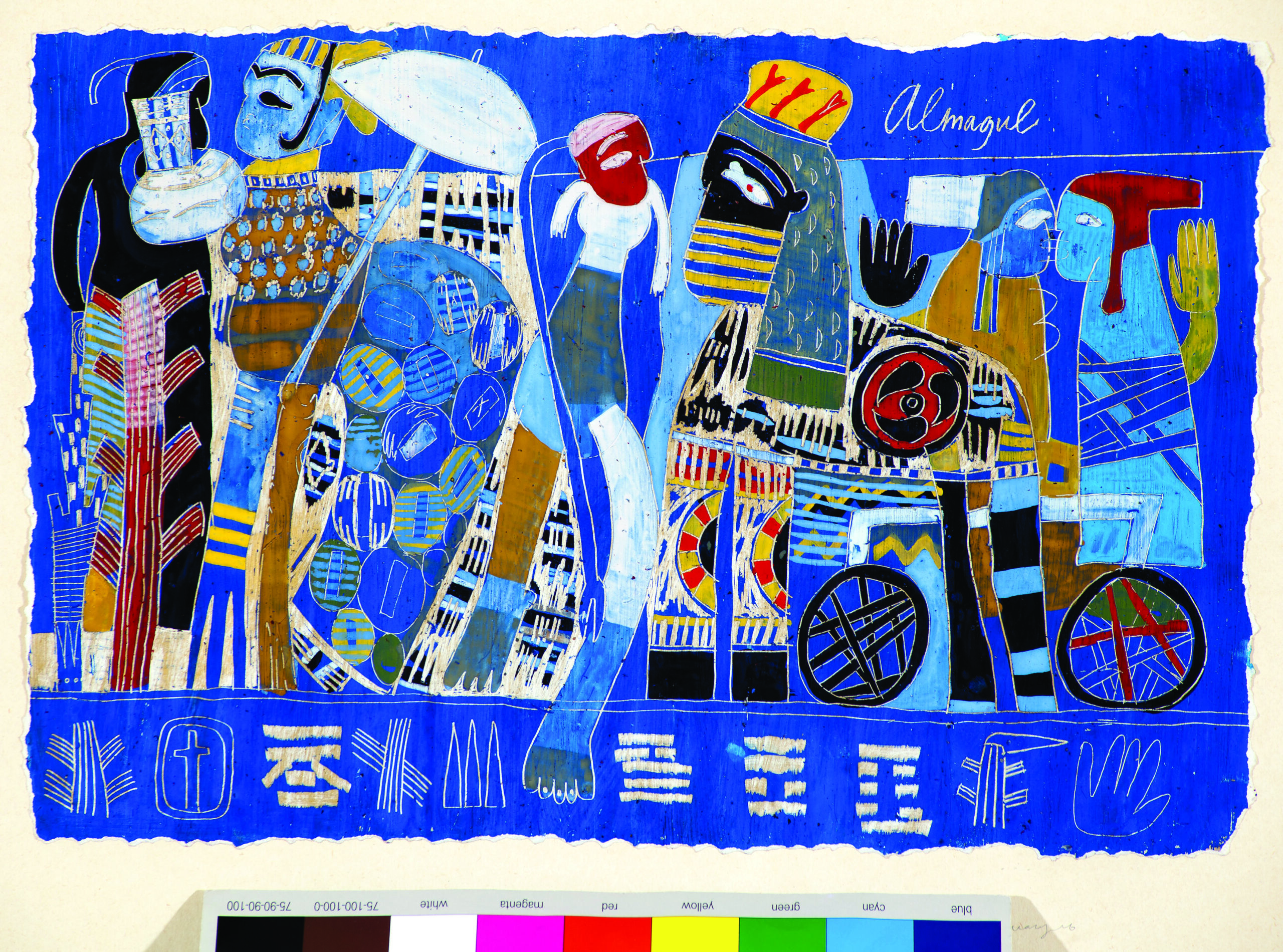

Image: Almagul Menlibayeva

This series of surreal images is from the video Transoxiana Dream, by one of Central Asia’s pioneering contemporary artists, Almagul Menlibayeva. The Times of Central Asia attended her major solo show, I Understand Everything, curated by Thai curator Gritiya Gaweewong, a powerful exploration of memory, trauma, and identity, which provides the “treble clef” for the opening of the Almaty Museum of Arts.

The show brings together works spanning decades, from Menlibayeva’s early paintings and collages in the 1980s, to her recent internationally recognized video and photography works. Through a variety of mediums, she charts the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ecological devastation of Kazakhstan, and suppressed cultural memory.

Almagul Menlibayeva, People Talking against a Blue Background, 1988; image: Almaty Museum of Arts

As always in her practice, the feminine and feminist narratives are at the forefront. Menlibayeva’s women are at times bound with nature or with military rule, alternately merciful or merciless. Her works tackle ecological concerns, tying them directly to the destruction of patriarchy.

“For us, opening our program with Menlibayeva’s show was highly significant,” says Meruyert Kaliyeva, the museum’s artistic director. “She is a pioneering Central Asian artist who is known internationally but at the same time has always dealt with topics and themes that are important locally.”

A New Museum in Almaty

The inauguration of the Almaty Museum of Arts represents a decisive step in shaping Kazakhstan’s creative future. As the country’s first large-scale contemporary art museum, it houses over 700 works collected across three decades, offering a panoramic view of modern Kazakh art while opening pathways to Central Asian and international dialogues.

Almaty Museum of Arts; image: Alexey Poptsov

Its mission extends beyond exhibitions: the institution positions itself as a center for education, research, and collaboration, aiming to nurture local artists and connect them to global networks. For Kazakhstan, long without a dedicated contemporary art museum, this moment signals a new era, one in which cultural identity is asserted with confidence, and the arts are recognized as a vital force for national memory as well as international visibility.

Kaliyeva emphasizes how essential it is that Kazakh artists now have a platform where voices once peripheral to national culture can take center stage. She also stresses the urgency of the moment: in a world reshaped by geopolitical fractures, climate crises, and cultural decolonization, this opening is necessary: “It’s a moment for Kazakhstan to assert its own narratives, to host memory and imagination on its own terms.”

Meruyert Kaliyeva; image: Anvar Rakishev

Kaliyeva situates the institution in Kazakhstan’s broader cultural history, highlighting how the country has long been a “laboratory of friendship,” forged through waves of migration and displacement, from deported Koreans to Soviet dissidents. In her view, the museum must serve as a decolonial institution, allowing Kazakhs to reclaim identity apart from Soviet ideology. “This sentiment began a long time ago when Kazakh people started to look for their own identity, but it became especially important after the war in Ukraine,” she observes.

Nurlan Smagulov, the museum’s founder, frames his role as one of stewardship as much as ownership: “It’s a lot of responsibility because Kazakhstan never had a contemporary art museum of this kind.”

Smagulov’s love affair with art began in his youth, amidst the halls of Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. At just 17 years old, he found solace and inspiration in the works of the Impressionists, igniting a passion that would shape his life’s journey.

Nurlan Smagulov; image: Almaty Museum of Arts

“Growing up in what used to be the Soviet Union, everything was prohibited,” he recounts. “Going abroad was impossible. Nobody was buying art. All the exhibitions I saw, I saw on TV. The artists could only paint in the style of Socialist Realism. There was a very strict censorship. There was no freedom in art.”

Smagulov began building his collection in the early 1990s, focusing on local artists whose works resonated with his own experiences and memories. These acquisitions now form the basis of the museum’s permanent holdings. Today, his collection spans several generations of artists, from the pioneering figures of the 1960s and 70s to the contemporary visionaries of today. In the absence of a proper contemporary art museum, the focus on Kazakh and Central Asian art is particularly significant.

Zhanatai Sharden, Aksai Mountains; image: Almaty Museum of Arts

The permanent collection also includes works by international artists such as Richard Serra, Anselm Kiefer, Bill Viola, and Yayoi Kusama. These pieces serve as a bridge between Kazakhstan and the global contemporary art scene, fostering a dialogue between cultures and artistic traditions.

“I feel that I’ve written a new story,” says Smagulov. “I feel joy that many people will come here and they will be proud of their country.”

The Permanent Collection

The museum’s inaugural exhibition, curated by Latvian curator Inga Lace, is titled Konakhtar (“guests”), emphasizing the theme of hospitality that has shaped Kazakh culture for centuries. “A thing about hospitality is that in nomadic times, guests would also bring with them interesting stories,” says Lace. “So, hospitality was seen as a way of survival, but also a way of communicating.”

The works she places in the foreground open with festive gatherings, such as Aisha Galibaeva’s Shepherd’s Feast, where traditions of Kazakh conviviality are refracted through the Soviet lens. Yet hospitality, Lace reminds us, is not always voluntary. Soviet-era forced displacements – Koreans, dissidents, or those sent during the Virgin Lands campaign – reshaped communities. “Hospitality emerges as a very political act,” she notes.

The exhibition traces how these histories live on in artistic visions, whether through music, as in Dina Pilsava’s dombra performances appropriated by Soviet officials, or in avant-garde reinterpretations of nomadic forms by the generation of the 1960s.

“This collection and this museum is built as this kind of dialogue,” says Lace. “So, we have Kazakh art and the collection of the founder as the nucleus, and then international art to have this bridge with the global contemporary scene.”

Inga Lace; image: Almaty Museum of Arts

Lace’s presentation concludes with a meditation on migration and cosmopolitanism, embodied in artists like Yevgeny Sidorkin, who illustrated Kazakh folk tales, or Sergey Kalmykov, who adopted Kazakhstan as the site of his cosmic experiments. For Lace, these works collectively express the desire to “see the past and also imagine different futures through the art of the region and the country.”

Both founders see the museum as a catalyst for change, hoping that international audiences will be more and more encouraged to come to Almaty. Presenting artists insisting on sharing voices across regions and histories, the Almaty Museum of Arts gathers fragments of memory, trauma, and resilience, weaving them into a cultural space that allows Kazakhstan to see itself anew, and to be seen by the world.

Almagul Menlibayeva, People and Animals, 1997; image: Almaty Museum of Arts

Almagul Menlibayeva perhaps put it best: “When we look at Kazakhstan, we see a strong connection with a number of countries and regions, from Europe, Siberia, Japan, Korea, but also China, and, of course, the Middle East,” she says. “I found that for me it was easy to understand, even if some places don’t understand each other. I feel like I’m a satellite, moving between regions and attempting to understand everything.”