World Bank: Poverty Falls in Kazakhstan, but Inequality and Child Poverty Persist

The World Bank has released a comprehensive report on poverty in Kazakhstan, analyzing trends from 2006 to 2021. Presented to journalists in Almaty, the report paints a detailed picture of the country’s evolving socio-economic landscape.

Defining Poverty

Poverty is broadly defined as the inability to meet basic human needs, including food, clothing, clean water, sanitation, education, and healthcare. One standard measure is the subsistence minimum set by the government.

As of 2021, the international poverty line was $3 per person per day in low-income countries. For upper-middle-income economies like Kazakhstan, the threshold was set at $8.30 per day.

@pip.worldbank.org

From Poverty to the Middle Class

Over 15 years, Kazakhstan witnessed substantial economic growth. Per capita consumption doubled, and GDP per capita rose from 548,900 to 791,300 tenge (KZT). An estimated six million people were lifted out of poverty, and the country advanced into the category of upper-middle-income economies.

The World Bank identifies three distinct phases of development:

- 2006-2013 – Growth: Economic expansion and proactive social policies reduced poverty from 49.5% to 11.1%

- 2014-2016 – Crisis: A sharp decline in oil prices and the devaluation of the tenge saw poverty spike to 20.2%

- 2016-2021 – Stabilization: Economic recovery brought the poverty rate down to 8.5%

@worldbank.org

A Rising Middle Class

Between 2006 and 2021, the share of Kazakhstan’s population considered middle class increased from 26 percent to 67 percent. The World Bank defines the middle class as individuals who are neither poor nor economically vulnerable.

This growth was driven by rising incomes, pensions, and social assistance programs. However, progress began to slow after 2013 due to ongoing structural challenges, low productivity, dependence on extractive industries, and a weak private sector.

Child Poverty: An Alarming Trend

National gains have not eliminated regional disparities. In the Turkistan region, poverty rose from 14.4 percent in 2006 to 24 percent in 2021.

@worldbank.org

Demographic shifts in poverty are also concerning. The poor are increasingly younger, less educated, and from large families. Child poverty is especially acute: 13% of children live below the poverty line, comprising 40% of the country’s poor. In other words, every eighth child in Kazakhstan is living in poverty.

@worldbank.org

Consumption and Inequality

Rising consumption, measured via purchasing power parity (PPP), has been the main driver of poverty reduction. Indicators like the Big Mac Index offer accessible insights into shifts in purchasing power.

Growth in incomes, pensions, and the small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sector also contributed, while emergency government support during the COVID-19 pandemic helped avert a sharp decline in living standards.

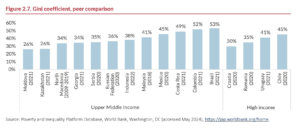

Nevertheless, inequality is on the rise. Since 2016, the Gini Index has shown a growing gap. The wealthiest 10% of Kazakhstanis now spend three times more than the poorest 10%. While this inequality remains moderate by global standards, the upward trend is cause for concern.

@worldbank.org

Looking Ahead

World Bank analysts acknowledge Kazakhstan’s progress in reducing poverty. However, they caution that traditional growth strategies have reached their limits.

To ensure sustainable development, Kazakhstan must pursue deep structural reforms: boosting productivity, fostering private sector growth, and tackling stark regional inequalities. Only through such measures can the country achieve inclusive prosperity and secure long-term well-being for all its citizens.