Kyrgyzstan’s Wages Lowest Among EAEU Countries

Kyrgyzstan has the lowest average monthly wage among its fellow Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) members, an economic integration bloc that includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia.

Kyrgyzstan has the lowest average monthly wage among its fellow Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) members, an economic integration bloc that includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia.

The third day of the World Nomad Games, themed as the “Gathering of the Great Steppe,” saw events taking place across Astana. TCA went to the Martial Arts Palace and the Alau Ice Palace to take in the in the Koresh (Tatar belt wrestling), Assyk atu, Mas-wrestling, Kurash, and Kazakh kuresi. Watch our video highlights from day three here:

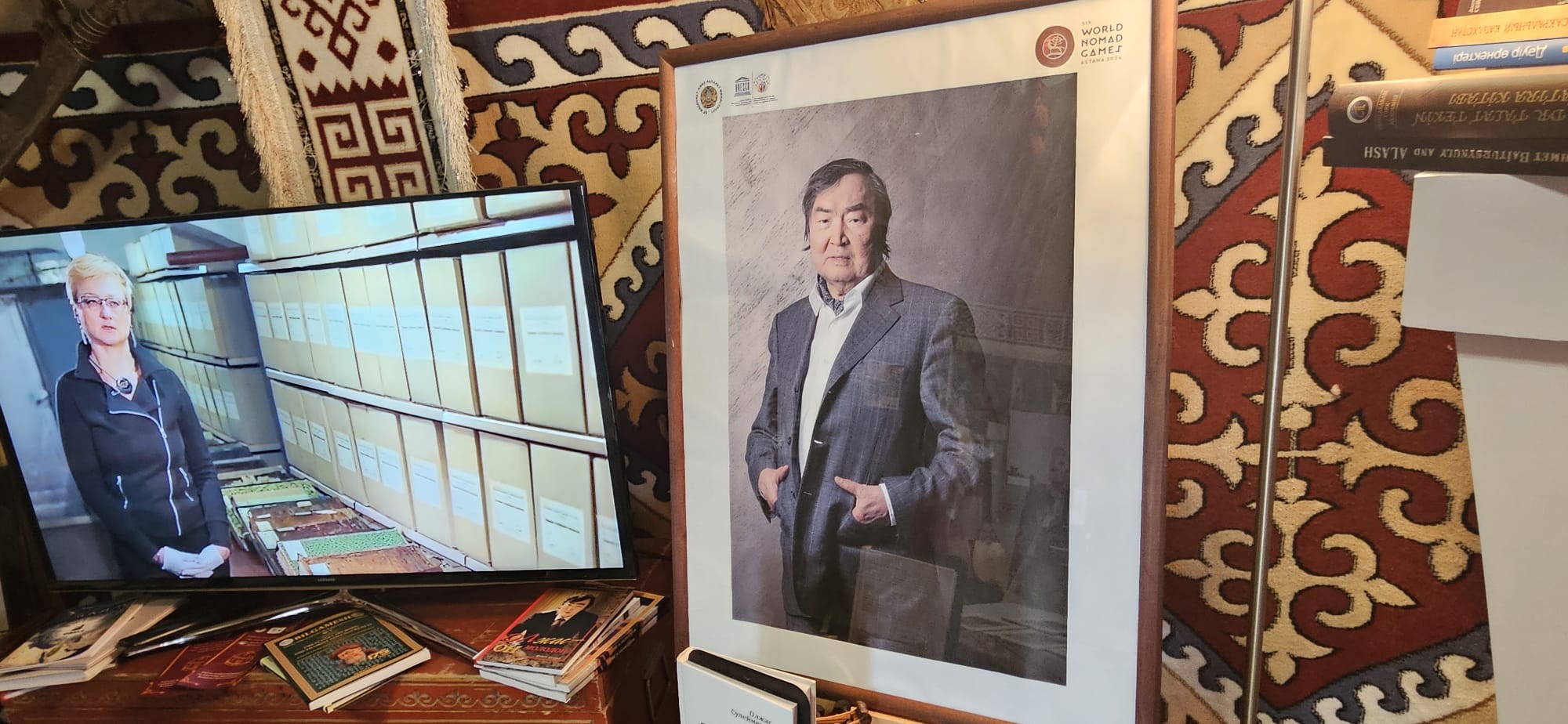

Nestled among the yurts of the 2024 World Nomad Games Ethnoaul (Ethnic Village), one yurt in particular provided a promotional VIP space for the distinguished Russophone poet, politician, UNESCO ambassador, International Democratic Party Chairman of the People’s Congress of Kazakhstan, and anti-nuclear activist Olzhas Suleimenov. A hushed silence spread inside the circumference of the AZ i YA (a Russian play on the word “Asia”) yurt, named in honor of Suleimenov’s 1975 book about the conceivable Turkic origin of the epic Old East Slavic poem The Tale of Igor’s Campaign. Bystanders were ushered out when the Almaty-born Suleimenov arrived. The aforementioned book caused controversy when it was released in the Soviet era and was almost banned when Suleimenov was accused of “national chauvinism” and “glorifying feudal nomadic culture.” By contrast, the purpose of the AZ i YA yurt is to educate the unenlightened and celebrate the thirteen elements of “Kazakhstan’s Rich Cultural Heritage.”

Those thirteen elements, as explained by the yurt’s translator and self-proclaimed “young scientist” Dana Tursynova, include Aitysh, a spoken word poetry contest with dueling dombra (two-string instrument), or the Kyrgyz komuz (two or three strings), in which two protagonists improvise on the topics of opposing ideas, retorts, and general frustrations. Tursynova described it as “conveying political problems” and “the sound of a nation [aimed at] the government.” At a neighboring yurt, Aitysh—delivered with gravelly belligerence—was audibly comparable with a modern battle rap. Another element is Nasreddin Hodja, a 13th-century folklore storyteller who—similar to the Aitysh tradition—used humor to air political grievances and other types of narrative.

A further element is Korkyt-Ata (translated from Kazakh as “granddad”), a 9th-century philosopher, who, in his pursuit of immortality discovered that death was always waiting for him. As he gained enlightenment, he somehow had enough free time to craft the kobyz, an ancient Turkic stringed instrument. Thus, he is known as the founder of Kazakh string and bow instruments. The yurt, the round portable homes of the nomads, is an element, as is orteke, where the dombra musician surpasses the average one-man-band status by operating moving wooden puppets connected to his fingers via the strings to convey multi-task theater.

The sports elements comprise kazakhsha kures, traditional Kazakh wrestling, which in recent times has traded the long-established grass turf for a mod con carpet, board-type games, such as Assyk, designed to sharpen the intellectual and physical development of children, and Kusbegilik, or hunting with birds of prey, a Kazakh cultural heritage as well as a major sport in the WNG. Edible elements combine katyrma flatbread, an important part of Kazakhstan’s communal relations in the interchange of goodwill (e.g. “have a good life”) when sharing the bread, and horse breeder festivities, where kumis, fermented horse milk, is the culinary highlight.

The main heading of the yurt’s pamphlet handout is the substantially worded International Centre for the Rapprochement of Cultures Under the Auspices of UNESCO. In one small yurt (on one Great Steppe), the cultural round-up of folklore, tradition, and heritage sits at an interesting intersection with the Suleimenov-led Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement to shut down the nuclear sites in Nevada and Semipalatinsk Oblast in Kazakhstan, the latter being a hot topic in the AZ i YA yurt. Central Asia’s efforts to reinvigorate nomadic culture in a post-Soviet era, do, however, tally with a line (displayed a the entrance of the yurt) from one of Suleimenov’s poems: “There is no East, There is no West, There is a big word – EARTH!”

Though the World Nomad Games are often defined as an “international sport competition dedicated to ethnic sports,” the event is so much more. As described by Sultan Raev, General Secretary of the International Organization of Turkic Culture, even the sports themselves are “not about physical strength. They are about spiritual endurance.”

Today, TCA took in the wider cultural context behind the Games, exploring the celebration of identity which the event represents.

At the very heart of the Games, the Ethnoaul acts as a huge showcase for cultural heritage. Each day, the Dumandy dala (Joyful Steppe) concerts offer a platform for groups from all over the country: ethno-folklore ensembles, Kazakh national orchestras, soloists, dance troupes, and more. From dueling dombras – a traditional two-stringed instrument – to traditional Kazakh music vaguely akin to rap in which the protagonists air their grievances, nomadic culture is truly alive here, not just as a historical curiosity, but as a vibrant heart belonging to the people; a heart which is equally at home in the modern world.

Indeed, as stated by President Tokayev in his keynote speech at the opening ceremony: “the great nomadic life will never cease to exist. Even amid globalization, the nomadic lifestyle that existed for a thousand years is reviving and taking a new shape. Modern nomads are making efforts to reclaim a central place in history. We are moving and traveling easily all over the world in search of education and job opportunities.”

Since Estonia became the first country to offer a “digital nomad visa” in 2020, sixty-five more nations have followed suit, with their number continuing to expand. Nomad culture, it seems, is alive and kicking.

Reconstruction of the costume and weapons of an 11th century Sarmatian leader; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The Ethnoaul hosts yurts from across the nation, where representatives of regions have gathered to display their distinct history and traditions, from a reconstruction of the costume and weapons of an 11th century Sarmatian leader whose remains were found in a burial mound in Atyrau in 1999, to the Shymkent region’s focus on the mercantile activities which made the Great Silk Road great. With a traditional purple-suited ensemble from Akmola playing as young girls in long green dresses and sequined headdresses pirouette, it certainly makes for a tremendous feast of colors, sights and sounds.

Young dancer twirl; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

This sense of national pride in tradition is not lost on visitors from neighboring lands, as evinced by the preponderance of Kyrgyz men in traditional kalpaks – the tall, traditional felt hat designed to allow air to circulate whilst resembling a peak from the Tien Shan Mountains.

A group from Akmola serenade the croed; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The Games act as a showcase for these identities, and an opportunity to at once celebrate and reenforce them whilst sharing them with the wider world. In an era when the specters of Soviet times are being dismantled at an ever-increasing pace in the face of global conflict, each of these unique lands is shaping itself in the 21st century in part by delving into and reclaiming their long-supressed past; and long may it continue.

In Japan on September 9, Kyrgyzstan’s Minister of Energy, Taalaibek Ibrayev, met with Ken Saito, Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, who oversees the country’s energy policy.

The two ministries signed a memorandum of cooperation to implement joint projects in green energy.

The aim of the new partnership is to expand energy cooperation between Japan and Kyrgyzstan, and developing sectors such as energy efficiency, renewable energy, hydrogen energy, ammonia, carbon recycling, and high-efficiency electricity generation.

While visiting Japan last November, Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov held talks with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. Cooperation in the energy sector was one of the issues that they discussed.

During the visit, Japarov invited Japanese companies to use the opportunities and potential for cooperation with Kyrgyzstan to develop renewable energy sources and construct hydropower plants.

Although the season has yet to officially open, cotton harvesting is already underway in Turkmenistan. As reported by Azatlyk correspondents, workers, including budgetary employees in the Lebap province, are being watched by Ministry of National Security (MNS) officers. These officers, tasked with preventing information about forced labor being leaked, have forbidden the use of cell phones in the fields.

Turkmenistan has long been criticized for its use of forced labor on cotton plantations, and authorities continue to hide the reality.

The increased control by security agencies coincides with a briefing in Ashgabat on measures discussed in collaboration with the International Labor Organization (ILO), to eradicate child and forced labor.

Despite official bans, including an order issued by Labor Minister Muhammetseyit Sylabov in July this year prohibiting the employment of children under 18, child labor continues in some regions, including Kerki and Chardjev etraps, and teachers confirm that high school students, with their parents’ consent, participate in cotton picking.

At the same time, cotton pickers complain about underpayment. Employers also repeatedly renege on promised rates of pay and in Lebap, citing the poor quality of the cotton harvested, are known to withhold up to 50% of their workers’ salaries, leading to inevitable conflict.

Despite orders issued by the authorities to increase pickers’ wages in accordance with the state’s procurement prices for cotton, the workers’ situation shows no sign of improving.