In the spring of 2024, the world’s attention turned to Astana as the trial of former minister Kuandyk Bishimbayev unfolded. Accused of the brutal murder of his common-law wife, Saltanat Nukenova, the proceedings were broadcast live, marking the region’s first live-streamed murder trial, which was widely followed like a reality show. The livestream drew hundreds of thousands across Kazakhstan, with daily clips dissected on TikTok and Telegram channels, a public fixation that turned the courtroom into a national arena

Under intense public pressure, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed a landmark legislative reform popularly dubbed “Saltanat’s Law.” These amendments enhanced protections for women and children. The most consequential change was re-criminalizing battery and intentional infliction of minor bodily harm — offences frequently present in domestic violence cases — which had previously been treated as administrative violations.

Now, over a year later, the emotional urgency has waned, giving way to the realities of implementation. The transition from legislative success to consistent enforcement has revealed systemic resistance from conservative communities and infrastructural gaps.

A Statistical Paradox

The initial police data may appear counterintuitive. Rather than declining, reported cases of domestic abuse surged following the law’s passage. According to the General Prosecutor’s Office and the Institute of Legislation, such offenses increased by 238% within a year, rising from 406 to 1,370 criminal cases by mid-2025. Interior Ministry data shows that more than 70,000 protective orders were issued nationwide in the first nine months of 2025, a surge driven by mandatory registration and proactive police intervention.

Experts caution against interpreting this spike as a rise in violence, however. Instead, it reflects the exposure of previously hidden abuse. From 1 July 2023, police could start administrative domestic-violence cases without a victim’s complaint. The 2024 Saltanat Law then reinforced this proactive approach in the criminal sphere.

The law also removed the option for repeated reconciliation. Previously, over 60% of domestic violence cases collapsed when victims, often under familial pressure, withdrew their statements. Now, cases proceed regardless. As a result, administrative arrests have doubled, supporting the argument long made by human rights activists: it is the inevitability of punishment, not its severity, that disrupts the cycle of abuse.

Uneven Enforcement Across Regions

The law’s effectiveness varies significantly by region. High reporting rates in cities such as Almaty and Astana and in northern industrial regions often reflect improved enforcement rather than increased violence. In these areas, women are more aware of their rights, and law enforcement responds accordingly. In Astana and Almaty, police units trained specifically on domestic violence now conduct routine checks and intervene based on neighbour reports or video evidence, even without a formal complaint.

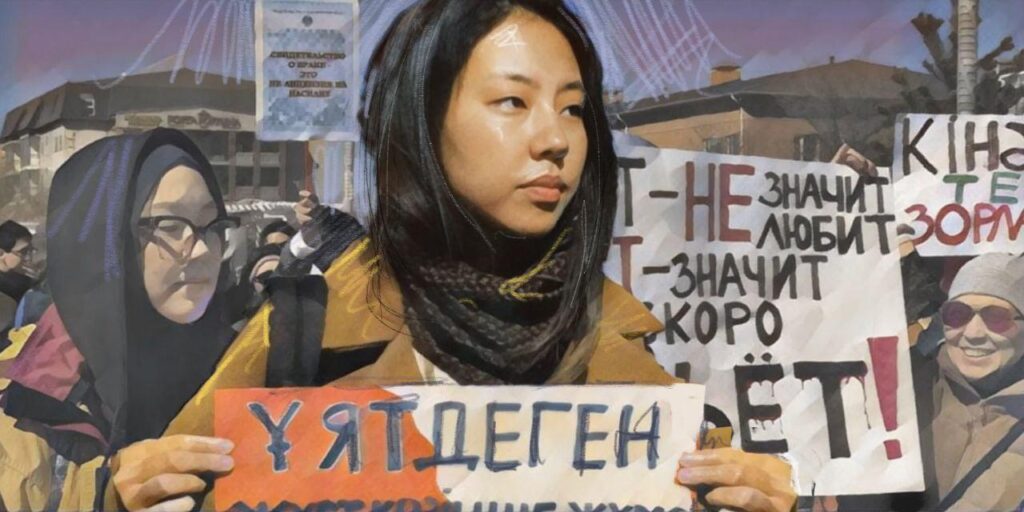

Conversely, in more traditional regions, particularly Turkestan, Zhambyl, and parts of western Kazakhstan, domestic violence often remains underreported. Here, entrenched patriarchal norms and the cultural concept of uyat (shame) discourage women from seeking legal help. Local police and community leaders sometimes view reporting abuse as a family disgrace and pressure women to resolve disputes privately.

In the Turkestan region, activists recount cases in which officers still advise couples to “make peace,” reflecting lingering beliefs that preserving family unity outweighs legal intervention. Human rights advocates describe this as “quiet obstruction”. While the law is uniform nationwide, its application hinges on regional urbanization and secularization levels.

Infrastructure Shortfalls

Another critical weakness lies in the support infrastructure. The law has increased penalties for perpetrators but has not adequately addressed the safety of victims before trial. Kazakhstan operates around 70–75 crisis centres, roughly 60 of which provide shelter beds. Experts and NGOs argue this is still an insufficient number for a population of 20 million. Shelter directors say that many women only seek help after repeated violence, often with children in tow, because they fear economic hardship or social ostracism, pressures that no criminal statute can override. Many shelters are NGO-run and depend on inconsistent grant funding. In rural areas, women often have no alternative but to remain in the same household as their abuser, placing them at further risk.

Cultural Shifts and Political Polarization

The law has also intensified political divisions. Conservative groups, including the Union of Parents of Kazakhstan, have voiced strong opposition, framing the law as a threat to traditional family values and an imposition of Western-style justice. These critics exploit societal fears, suggesting that minor disciplinary actions could result in the removal of children by the state. The government walks a fine line, championing human rights while seeking not to alienate its conservative base.

Yet, despite these challenges, the Saltanat Law marks a cultural turning point. For the first time in the country’s post-Soviet history, domestic violence is no longer a taboo subject. The law alone cannot eradicate abuse overnight, but it has dismantled a longstanding pillar of violence: the expectation of impunity. Officials have pushed back against conservative fears, noting that child-protection services have neither the mandate nor the capacity to “seize” children over minor discipline — a central claim of anti-law activists.

The Road Ahead

The future of this reform hinges not on further legal tweaks, but on long-term societal change. Encouragingly, a generational shift is underway. A growing number of women, especially younger ones, reject the notion of victim-blaming and are less tolerant of domestic violence. National surveys show that the share of women who justify a husband hitting his wife has fallen from 15% in 2015 to just 4% today, a dramatic shift in attitudes within a single decade.

In rural areas, the proportion of women who believe a husband has the right to use force has fallen from 20.6% to 6.8% over the past decade. Among urban women, the figure is just 2.6%. Notably, among women under 30, acceptance of domestic violence is practically non-existent.

While the Saltanat Law is not a panacea, it is a critical first step in breaking the cycle of silence, shame, and abuse. Its success will depend on continued societal transformation, expanded victim support, and the resilience of those pushing for justice.