Kinship Clans in Modern Kazakhstan: Historical Continuity and New Realities

Ancestral ties are seemingly embedded in the DNA of every Kazakh. This tradition, rooted in antiquity, reflects the clan structure that historically shaped Kazakh society. The notions of zhuz (a set of clans) and ru (clan) largely determined the social organization of the nomadic lifestyle. Kazakh society traditionally consisted of three zhuzes, the Older, Middle, and Younger which in turn united many clans.

The zhuzes were large tribal unions, a kind of higher-level “horde” that included dozens or even hundreds of distinct clan groups (ru), while ru referred specifically to a group of close blood relatives. Such clan structures formed the basis of traditional society.

Historical Roots: The System of Zhuzes and Shezhire

The origin of the three Kazakh zhuzes remains a subject of historical debate. In early written sources from the 17th century, the names of the zhuzes had not yet been formalized. Chronicles described only a geographic custom: those living in the upper reaches of a river were called the “Big zhuz,” those in the middle the “Middle zhuz,” and those in the lower reaches the “Younger zhuz.”

The 16th-century work Majmu al-Garaib mentions Kazakhs but notes that the terms Uly zhuz, Orta zhuz, and Kishi zhuz were not yet in use.

The classical three-zhuz system only fully formed by the late 17th to early 18th century, during the reign of Tauke Khan (1680-1715), when the Kazakhs united under a single Kazakh Khanate. According to a legend recorded by traveler G. N. Potanin, one ruler gathered 300 warriors and divided them into three groups: the first hundred, Uly zhuz, were settled upstream along the Syr Darya; the second hundred, Orta zhuz, in the middle; and the last hundred, led by the chief Alshin, downstream as Kishi zhuz.

These legends provide a cultural explanation for the emergence of the zhuzes, though historians stress there is no single agreed version. Hypotheses range from military-administrative divisions into “wings” to the influence of geography and climate across Semirechye, Saryarka, and Western Kazakhstan.

Alongside the zhuz system, clan identity was reinforced through genealogical chronicles, shezhire, in which Kazakhs recorded their ancestors’ names and clan history. Knowledge of seven generations (jeti ata) was obligatory for every Kazakh and was absorbed “with mother’s milk”.

These genealogies had practical implications: knowing one’s lineage helped determine kinship laws, including prohibitions on marrying within the same clan.

The clan was not just a social structure, but a fundamental part of identity. As publicist Khakim Omar wrote: “The main idea of the shezhire is revealed in the close connection of ancestors’ and descendants’ names, in the continuity of generations,” allowing a person, through genealogy, “to define their place in the world”.

Transformation of Tradition in the Soviet Era

Under Soviet rule, internationalism and a break from “tribalism” were officially promoted. Yet in practice, the clan system continued to operate informally as a mechanism of social mobility and legitimacy. While divisions into zhuzes and clans were no longer legally recognized, they endured as a way of thinking, a cultural filter through which many Kazakhs understood the world.

Historian Nurbulat Masanov noted: “Zhuzes – clans – tribes in Kazakhstan never functioned as organizational structures… In Kazakhstan, this was primarily a way of interpreting processes through kinship ties”. In other words, kinship continued to play the role of an “invisible hand,” particularly in informal settings.

Perceptions of leaders were often shaped by clan affiliation. For instance, Dinmukhamed Kunaev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan in the 1960s-1980s, was seen by many as “their own” because he came from the Older zhuz, ysty clan. Many in that zhuz felt pride that “their” person led the republic, while others felt less connection.

Informal patronage also persisted: historians note that Kunaev often surrounded himself with trusted associates from similar regional or clan backgrounds.

Even though kinship was not openly discussed in Soviet times, the practice of agaiynshylyk (nepotism) quietly endured.

Modern Perception: How Kinship Ties Live Today

To understand how zhuzes and clans are viewed today, The Times of Central Asia, spoke with citizens from different regions of Kazakhstan. Despite globalization, many still see these traditional affiliations as an important part of personal and collective identity, even as their meanings evolve.

Aigerim Ospanova, 24, lawyer:

“When I studied at university in Aktobe, I often heard the question: ‘What clan are you from?’ It wasn’t about connections or privileges, more a way to quickly find common ground. Clan is like a password in the system: it opens access to trust.”

In larger cities like Almaty and Astana, young people generally pay less attention to formal clan affiliation, seeing it more as cultural knowledge, a link to the past.

Daniyar Olkhabek, 20, IT specialist (Astana):

“My grandmother still asks what ru my friends are from. While I don’t give it much importance, I understand that for the older generation it’s a way to preserve tradition. It doesn’t bother me, on the contrary, it reminds me where I come from.”

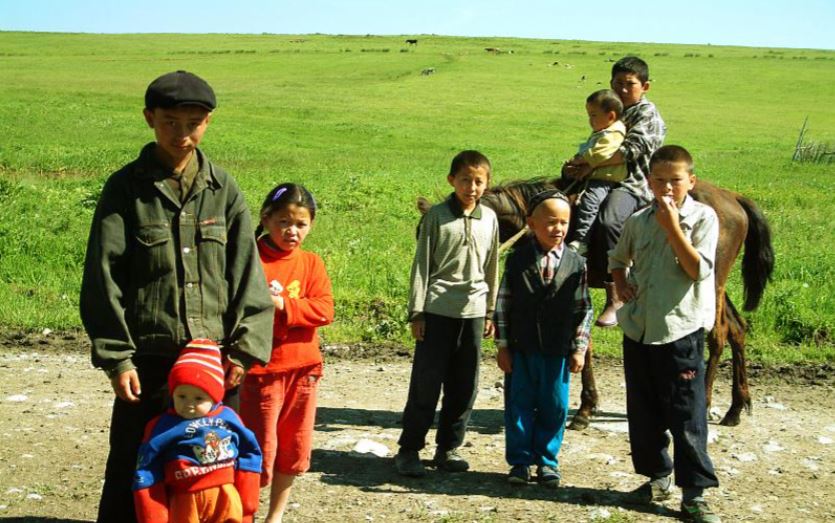

In western and southern Kazakhstan, especially in rural areas, kinship ties remain visible. However, even here, the meaning is shifting from exclusion to informal networks of trust and support.

Yerlan Baktybaev, 31, logistics specialist (Atyrau region):

“If someone is from my ru, it doesn’t mean I’ll promote him at work through connections. But we’ll likely be friends, if he’s really competent. It’s simply part of our culture of mutual support.”

For many young Kazakhs, especially those abroad, knowledge of genealogy remains a source of pride and solidarity. Shared ancestry can quickly build bridges between strangers.

Alen Ismailov, 25, master’s student (Almaty):

“When I went to study in Turkey, I met a guy from my ru. We instantly felt kinship, even though we were complete strangers. In a foreign country, that became a point of support, a very valuable feeling.”

Today’s youth tend to approach clan identity with flexibility. For most, it is a part of cultural heritage, not a rigid social label. Many prioritize personal achievement, education, and professional success over lineage.

Assel Akhmetova, 22, student (Taraz):

“I like knowing my zhuz and ru, it’s part of my identity. But I believe a person should be defined by their actions, not their clan. It’s good to know who you are and where you’re from, but you need to live with your own mind.”

Modern Kazakh youth stand at a crossroads between tradition and a globalized future. On one hand, they are raised to respect family and elders. On the other, post-Soviet generations are increasingly individualistic and ambition-driven. Research confirms this duality: many young Kazakhs simultaneously uphold family traditions and seek independence.

According to official surveys, 88% of young people say they trust their family members the most, demonstrating the enduring strength of traditional family values.

Yet, there is also a strong emphasis on competitiveness. Young people aspire to quality education, language skills, career advancement, and fair competition both at home and abroad.

In practice, this shift is evident in job-seeking behavior: young people rarely rely on relatives’ connections, instead trusting their own merit. Surveys show that more than 80% of urban youth oppose using zhuz or ru ties for employment, skills and professionalism matter more. At the same time, even the most “progressive” youth retain traditional knowledge: many still know their shezhire up to the seventh generation, respect marriage taboos within clans, and honor elders.

Today, two value systems coexist and are gradually reconciling in Kazakhstan. One is the traditional collectivist model, with its deep-rooted family and clan networks, ethnocultural codes, and the principle of ozimizdin adam (“our person”). The other is a modern individualist ethos, emphasizing education, mobility, and openness to the wider world.

These models are not mutually exclusive. Respect for ancestral heritage can go hand in hand with a pursuit of personal achievement in the 21st century. Perhaps in this synthesis, where a young Kazakh knows their roots but builds their future on their own merit, lies the formula for the country’s ongoing development.